Using the power of the brain to help kids communicate

Imagine if there was some technology that allowed people to interact with their environment using only their thoughts.

No, this isn’t the premise of a science fiction novel. This is reality for researchers, clinicians and clients at the Bloorview Research Institute (BRI).

For the past 20 years, Holland Bloorview’s PRISM Lab has been researching and developing assistive technologies. Under the leadership of Dr. Tom Chau, Vice President of Research, they have increasingly focused their attention on the emerging field of brain computer interfaces, or BCIs. Now, the Institute is at the forefront of pediatric brain computer interfacing (BCI) research.

“Brain-computer interfacing is an emerging area in rehabilitation science,” says Dr. Chau. “There’s no movement that’s required, no facial expressions, no eye gaze—simply what is generated in your brain.”

In Canada, there are some 6,000 children and youth whose physical disabilities mean that they could benefit from BCI technology.

To answer this call, the hospital opened up a BCI clinic last November. It is one of three such clinics in the world. The hospital is also partnering with the Alberta Children’s Hospital in Calgary and the Glenrose Rehabilitation Hospital in Edmonton to continue this cutting-edge research.

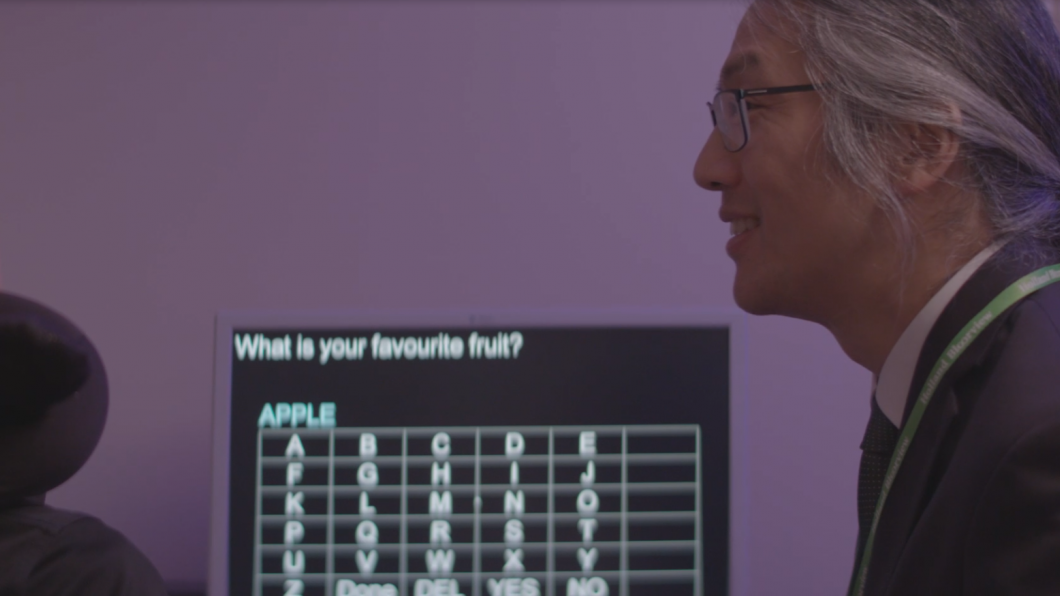

At the Holland Bloorview clinic, kids and youth wear sensors that detect brain activity and convert that into electrical signals. A computer then reads those signals and does the task the user imagines by connecting with nearby technology. A recent pilot program enabled children who had been receiving individual BCI training to participate in activities such as painting with a robotic ball, playing video games or racing toys alongside their siblings and family members.

“You might be surprised to see some of the technology and how far it's already gone. We actually have communication aids that you can control and you can type on a computer just using your brain activity,” says Dr. Chau.

The applications of BCI are also constantly evolving.

“This wasn’t available a decade or even a decade and a half ago,” notes Dr. Chau. “That's why research is so important at this point in time. There have been so many exciting developments on the scientific front that allow us to catapult childhood disability research to the next stage.”

For example, recent research shows that kids who are non-verbal may use BCI to express their thoughts simply by imagining speech. And thanks to the Holland Bloorview’s newly-launched research MRI, even more avenues can be explored.

“Using Holland Bloorview’s newly-launched research MRI, we will know which parts of the brain are activated when people do certain mental tasks. This will allow us to come up with new applications for BCI,” says Dr. Chau.

The research MRI will also enable researchers to understand how kids with acquired brain injuries engage with their surroundings.

“For children who have [an acquired brain injury], their brain may have reorganized over time,” says Dr. Chau. “With different scans, we’ll be able to understand the unique brain structure and function of different children so that we situate the sensors in places that are most appropriate for each child.”

Thanks to ground-breaking research at the Bloorview Research Institute, along with innovative technologies, BCIs are changing what is possible for kids with complex disabilities.