Is your teen being bullied? This book is for you

By Louise Kinross

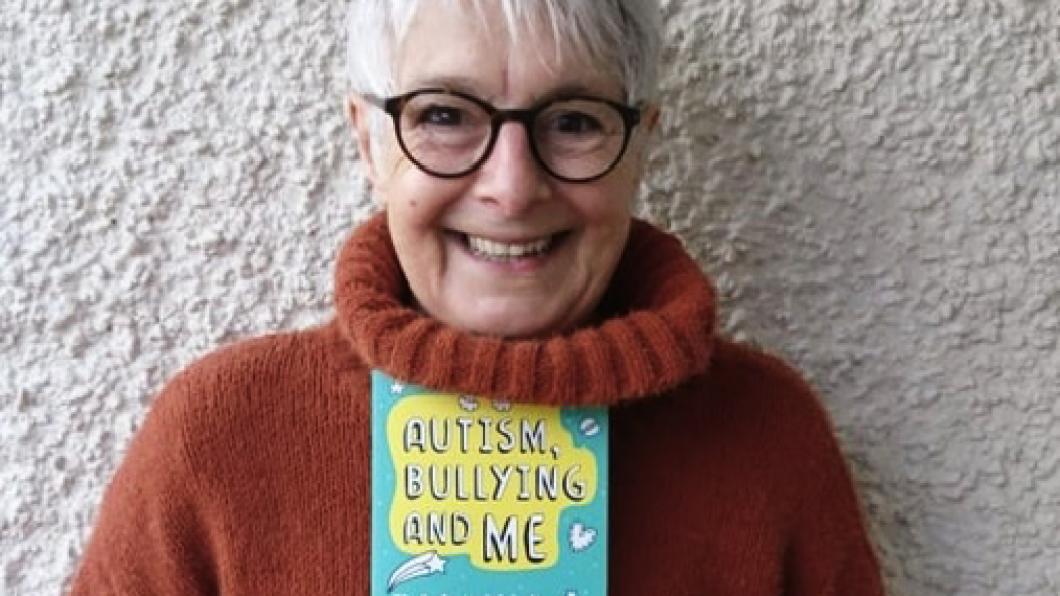

Autism, Bullying and Me is a warm, funny and practical book written by Emily Lovegrove, a psychologist in Wales who is known as The Bullying Doctor. While targeted to teens with autism, her book is helpful for any teen or adult struggling with bullying. Emily has researched strategies that help teens with facial differences, physical disabilities, autism and ADHD cope with bullying. "These are not quick, easy fixes, but things to work on," says Emily, who was diagnosed with autism at age 71. "We built up a whole raft of strategies, so that if one thing failed, you move on to the next thing. We found that after six weeks there was a positive difference, and after six months there was an even bigger positive difference." The book is written in an upbeat, accessible way that helps the reader understand why kids bully; how to calm your body so you can think more clearly when being bullied; and strategies to boost self-confidence and deal with depression.

BLOOM: We know that youth with autism are bullied at higher rates than their peers. Why did you want to write a book for autistic teens?

Emily Lovegrove: To be honest, I wanted to write a book for all teens who feel different in any way, so the title of the book is not the one that I chose, but the one that the publisher chose. Which is fair enough, that's their main market. I wanted it to be called Feeling Different, Bullying and Me. I think so many teenagers are really struggling with that sense of identity and what's normal and what isn't, what's okay and what isn't.

BLOOM: That's interesting, because I felt the book could be for anyone, child or adult alike.

Emily Lovegrove: I've had lots of lovely e-mails from adults who say 'I got this for my teen but I wouldn't hand it over until I had finished it.' One lady was 84 and she said 'I wish I'd had this before, but actually I still feel bullied by things and I'm going to get on and use it now.'

BLOOM: You write that confidence is the most important attribute in how people treat us. Can you speak to that?

Emily Lovegrove: What we would like is just to be ourselves and be acceptable and often that's not the case. Often people don't accept us for who we are and it can be difficult if you look in any way different or sound or behave in any way differently. So I feel what is important is not to deny who you are and to mask—in autism circles it's known as masking, when you put on a face that you think more or less is what ordinary people do.

A lot of teens are desperately trying to fit in but they're also desperate to be an individual. A lot go down the branded clothes route. They look at who is trendy and popular and go 'They're popular, so it must be that they wear those clothes or they do that particular thing.' Actually, that's not the reality. The reality is that it's the popular people who are confident about themselves. And they may not be very nice.

It's not that being confident equals being a lovely person—it doesn't. We can all think politically of people who are extraordinarily confident about themselves who we would not like to spend any time with. But having that confidence is important if you want to make friends.

Being pleased about the nice and positive things about yourself is a good way to kickstart that self-confidence.

BLOOM: You recommend teens identify three things they're happy with about themselves: a skill they value; something they like about their appearance; and something they like about their personalities.

Emily Lovegrove: This can change how you face the world. You might have to wear the most hideous school uniform and you may have looked in the mirror and thought 'I am fat, fed up and spotty,' but those things won't translate well into your facial expression and body language and the way you behave. If you feel those things, you're likely to stomp into school with a scowl on, or look as if you're trying to disappear, and that means others are likely to reject us, because we look as if we're rejecting them.

It's perfectly valid to feel the way you feel, but let's see what we can do to change today. What is a skill that you are proud of? You could say 'I'm good at football' or 'I like art' or 'I like playing my violin.' Right, choose one of those. Now, I need to know something positive about your personality. 'I'm quite friendly.' Great, we'll have that. And then something about the way you look. It could be that you are chuffed about your hair or about your left elbow, it could be anything. 'I'm quite smiley.' Fabulous! So now I want you to model being good at the violin, friendly and smiley, and obviously, there will be a difference in your facial expression and body language and the fact that you're more likely to approach others with that smile and to get a smile back. Not only do you feel better about yourself but other people view you more positively.

BLOOM: You explain what happens physiologically when someone is bullied: 'Your heart rate goes up, your breathing becomes shallow, your digestion stops. Your energy goes away from your brain, so it's almost impossible to think clearly and into your arms and legs so you can either fight or run away or freeze.' Why is it important for teens to understand that?

Emily Lovegrove: It's useful to know what's happening and to use that knowledge as a way of changing the outcome. Clearly, if someone is approaching you with a baseball bat, you do not fuss about what would be a positive way of coming out of this. You run and get help and that's a brilliant biological response to threat.

But if the threat is more psychological than physical, then knowing that all of those stress things are happening in your body, and you can't think clearly, is useful. Then you can do the deep breathing and grounding exercise that I describe.

BLOOM: I took notes on it.

What colour do you think of when you think of courage/bravery?

Stand with your feet apart, hands by your side.

Breathe in that colour, deep into your stomach. Feel it

heating up your stomach.

Now breathe that strong colour out as if it’s going

down your legs…past your knees…through your feet…

and through the floor. I want you to imagine that this

outgoing breath of yours is growing huge, massive

roots under the floor… Keep breathing out…keep

going…keep making those roots till you run out of

breath!

Your lungs will now take over and you will gasp in a

huge breath!

NOW oxygen is getting to your brain and you can

suddenly think more clearly!

Emily Lovegrove: Crucially the thinking part of your brain will now have oxygen and you can think logically about what you want to happen. If you have a tree caught in a gale and it has very shallow roots, it will just topple straight over. If you envision a tree with huge roots going down into the earth, even in a gale, you're not going to be blown over.

BLOOM: What are some ways that teens can defuse bullying?

Emily Lovegrove: A great way is to understand that other people if they're bullying, are not in a very good head space either. It's very tempting, when someone appears to be mean and hateful, to just label them—they're evil, they're horrible and I loathe them. Then get all of our friends on board.

That leads to warfare and is not really helpful.

If someone's being mean we don't want to deny that experience or the impact it has on you. You can give free range to that feeling of how cross you are. But for your sanity, you need to go forward. A good way there is to imagine why somebody might have been mean or bullied you.

I have not yet come across a child who's been accused of bullying who hasn't themselves been bullied in a different circumstance. Often people say stupid things without understanding what the meaning is or how it might affect someone else. People can be mean because they're incredibly stressed and it just comes out wrong. I think as parents that can happen, and as teachers that can happen.

So it's finding a reason behind why someone has behaved badly that might make us slightly less angry or depressed, which is a self-damaging thing. It's developing our empathy skills.

BLOOM: Is there a danger in placing the responsibility for change on the teen who is being bullied?

Emily Lovegrove: It's a question a lot of parents ask me. They say 'My child has not done anything wrong, why are you suggesting that they change?' which makes logical sense. Why would you change when it's not your fault? The reality is that it's very hard to change other people. In reality, we can only change how we deal with it, and I think that's an extraordinarily hard lesson to learn at any stage of life.

We gain our self-esteem in two ways. One is to do things we're very proud of and get self-esteem from a job well done.

The other way of raising your self-esteem is to put other people down so you go up in the social hierarchy and make them feel worse about themselves. That's also a very successful way of raising your self-esteem and a successful way of gaining popularity. People who bully are not going to change, because they've found a way that makes them feel good about themselves. Just saying 'You are bad, and you need to change,' or using ridicule or punishment—these are strategies that we've used over the years and they don't work. Kids who raise their self-esteem by putting others down tend to go for those who appear a bit weaker. That's another reason for us to work on our self-esteem personally.

What we have found is that kids who are more confident, who are more outgoing and who are more empathetic and understanding of others tend to get picked on less.

BLOOM: You have a chapter on practical ways teens who feel depressed can help themselves. Can you describe those.

Emily Lovegrove: When you're a teen, your whole brain is being rewired. It's doing the same amount of activity that it did when you were a baby, which is to say it's working massively hard at getting rid of junk and replacing it with synapses that appear to be more useful. Teens are often very tired and they tend to go to sleep later and wake later, and life is not geared toward that. Teens still have to get up at the crack of dawn and get off to school and they're often on a sleep deficit. When you're on a sleep deficit, it's harder to think rationally. All of that can be a lot to cope with and it often leads to depression. I wanted to share some relatively simple ways of getting out of that depression—or at least of being nice to yourself.

I use the example of writing up a diary so you can read it back and either giggle at some of the dafter things you did, or just recognize that actually I felt this way a couple of months ago, but the world didn't come to an end.

Having a list of really easy things you can do that help you to feel better is another one.

BLOOM: Is that where you write down things you enjoy on a scrap bit of paper and put it in a jar, and when you're feeling bad you pull one out?

Emily Lovegrove: Yes. It could be 'Pull on a pair of boots and a mack and get outside.' We know getting out into nature is is an incredibly restorative thing. But not all kids have access to that. When I asked kids in a survey if you're distressed, who do you talk to, in the main it was mothers, overwhelmingly, and more kids were likely to say they talk to the dog or cat or family pet before they went as far as talking to their dad. I found that very interesting. An idea to put in the jar could be sitting with a cat that purrs or a dog that snuggles you. Those aren't expensive things, they are just nice, life-affirming things.

When we feel low, we often can't think. People say 'Well, what would you like to do?' and the person says 'I don't know, I'm too miserable.' So you put your hand in the jar and you pull out a strip of paper and it says 'Go take a deep bubble bath' and you say 'Oh, okay, I'll do that.' Not only might it make you feel better, but the idea is to jog your brain from going round and round in circles.

BLOOM: I listened to an interview where you said you weren't diagnosed with autism until you were 71. How did it affect your childhood?

Emily Lovegrove: I look back and recognize that my childhood was pretty traumatic. I thought it was traumatic because I had been the most dreadful child. I was an awful baby who cried and wouldn't eat, and then a difficult child who was outspoken and I didn't have many friends. In the end, I made one friend as a teen who was a bully. I put up with it because at least I wasn't on my own.

So I think had I known I was autistic, it would have helped me to understand why I was the way I was, and to accept myself. I wasn't a 'dreadful, abnormal child,' which is what I was told. I was actually a 'perfectly normal autistic.' Changing the narrative has been extraordinarily hard work.

I am all for kids knowing their diagnosis. If a child is tested, then actually being able to tell them, in positive ways, 'Ah, you know the tests you did? It says you're on the autism spectrum. Isn't that interesting!' It's useful knowledge.

There are segments of society who spend an enormous amount of money in research to see if they can either cure autism or test for it in utero, so that people can be offered a termination. So there's a lot of negativity around autism.

The truth is that we're an enormously diverse race. Humans are incredibly diverse and we would do better to celebrate diversity than to try to see who we can hack away, just in case they're not financially viable all of the time. A lot of autistics are incredibly creative. When you look back at science, a lot of those really innovative thinkers would probably have been diagnosed autistic, because they had that huge attention to detail and that ability to think outside the box and to not just accept things because they've always been this way. A lot of autistics are quite keen to change the world.

BLOOM: How did you end up getting your autism diagnosis?

Emily Lovegrove: Initially, I had an adult daughter who was diagnosed. She sought a diagnosis because she read something about autism and thought 'This actually fits everything I've ever thought.' She pursued a diagnosis and was told instantly, 'Yup, there is no doubt you are autistic.'

I certainly didn't know anything about it when she was younger, because I'm married to another autistic and we had children who were autistic and ADHD and severely dyslexic. To us that was all quite normal. We're both academics and we just accepted that they were who they were. But it can cause difficulties later on. When my daughter found out she was autistic she said 'I am quite certain you are as well.' So I read a book about autistic women and I thought 'These women are perfectly normal, they're just like me.' It took a while for me to understand that actually, these women are not like me, I was like them.

BLOOM: What do you hope people take away from your book?

Emily Lovegrove: I hope they take away that there is something we can do about bullying. We can't stamp it out or just stop it like that. It's not possible. Being aggressive is part of being human, and sometimes we need people to be aggressive. But it's not a grim and awful subject. There are things we can do to feel better about ourselves when bullying has happened, as it happens to everybody. What we need to do are take strategies from those who deal with it successfully, and apply them to ourselves. This is meant to be a positive book.

BLOOM: Why don't you share that you're autistic in the introduction? When I read the introduction, I thought it would have helped teens reading it to connect with you.

Emily Lovegrove: I never thought of that. I do say it further on in the book. The thing is, I'm so used to being with lots of other autistics. I've been very much encouraged to say I'm an 'autistic psychologist,' but to me that would be like saying 'I'm a brown-eyed psychologist.' For me it's a given.