Understanding disability: Black, white or shades of grey?

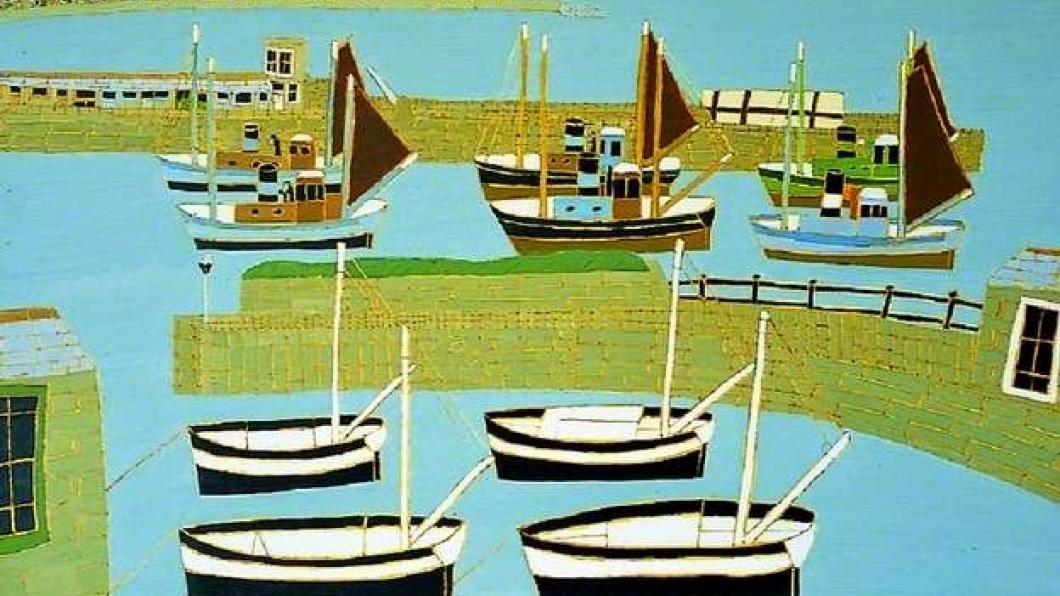

This painting by Bryan Pearce is part of a 38-image collection called BBC's Your Paintings.

By Louise Kinross

I'm intrigued by how such divergent perspectives on disability can pop up on social media in the same day.

Yesterday a colleague sent me a link to Tom Shakespeare's essay series on BBC Radio 3 called The Genius of Disability.

Shakespeare, a British writer and bioethicist, looks at the relationship between creativity and disability through a handful of disabled artists. "The stories I have found show that disability is no bar to success if an individual has talent and drive, and probably a fair share of luck," he says. Shakespeare holds these individuals up as role models for disabled people who have made "great creative contributions despite or because of their illness or impairment."

Something about the title, The Genius of Disability, hit me the wrong way. Isn't disability a hugely vast experience that varies from person to person, and even within a person, over time?

One of the artists is British painter Bryan Pearce, who was born in 1929 in St. Ives, Cornwall and had an intellectual disability.

In his piece on Pearce, Shakespeare asks: "Does an artist have to be clever?" Then he questions what happens when a person "can't fully reflect on what they're doing... Can you make great art by accident?"

I know nothing about Pearce's disability, but to suggest that he couldn't reflect on what he was doing, or that the paintings you see on this page were created by "accident," is pejorative and patronizing. Perhaps Pearce didn't think about his work in the same way that a person with average intelligence would, but maybe his experience of the world gave him a unique way of seeing and depicting things.

Then I thought about Shakespeare's use of the word "accident," implying that what Pearce produced was somehow random.

And then I couldn't help thinking about how random or "accidental" a large part of talent is, as opposed to being something you develop through hard work, whether you have a disability or not (I know, no one wants to hear this. Everyone wants to believe that they "deserve" their success by working so much harder than others. Everyone wants to pat themselves on the back). A large part of success, I believe, comes from natural ability that a person is gifted with at birth. Yes, they have to develop it, but they start with the tools. Some people, because of the types of disability they have, do not start with the same tools. There isn't any justice in this.

Another artist Shakespeare profiles is Lucy Jones, a British painter with cerebral palsy and dyslexia. He notes that Lucy doesn't want to be "classified as a disabled artist." I thought this was interesting, especially since Shakespeare was suggesting that disability itself fuelled artistic genius.

Growing up, no one could understand why Jones couldn't read, Shakespeare reports. She did well in art but not in her other courses. At some point she got a device that allowed her to express her thoughts by dictating them, as opposed to writing them down, and Shakespeare says: "Now she was getting good grades and feeling like a real person."

Does academic achievement make one a "real person?" Does that mean the painter Pearce, with the intellectual disability, was not a real person?

It seems we often fall into this black and white way of describing disability. Some people, like Shakespeare, who has a form of dwarfism, describe it as an advantage, while others look at it only as a deficit. We want to pin it down, not see it as fluid.

At the same time I was looking at Shakespeare's essays, I saw this piece by a parent of two children with Down syndrome. The mom writes about attending a conference for people with Down syndrome, and how she couldn't help feeling like one of her daughters, who has more significant disability, was excluded. "Everywhere you turned there were presentations about teens and adults with Down syndrome who'd exceeded all expectations," she writes. This included people getting their driver's licenses, going to college and getting married. There were also "videos of dancers, musicians or athletes with Down syndrome." While happy for their success, where did her daughter fit in? Was this an event for high-achievers only, she wondered? Were people now being labelled within the disability community in a hierarchy of value? Was it possible that a person with Down syndrome could attend a conference about and for people with Down syndrome and feel invisible?

The author questions whether we're "trying to sell everyone a better, more desirable version of the child and their disability."

Which brings me to what I thought was a brilliant post by a person with autism and physical disabilities. It's about how "able" folk try to separate her from her disabilities. These are people who constantly tell her things like: "Don't let your disabilities become your identity" and "You're a person with autism, not an autistic person" and "Your disabilities don't define you."

The truth, she says, is that "however much I try to ignore them, my disabilities really do limit me." Why should she have to deny that part of her experience or pretend it doesn't exist? "When people dismiss that, they often end up blaming me for my limitations," she says.

Isn't that what happened to the mom who attended the Down syndrome conference only to feel her child couldn't measure up?

Rather than a source of creative genius, this woman with autism sees her disabilities as physical limitations and a brain that works differently from most. But she's not "giving up, showing low confidence or calling myself weak...After a lifetime of being told my disabilities are weaknesses, I'm being strong without denying them. This is empowerment."

Which brings me to an interesting discussion I participated in yesterday at lunch here at Holland Bloorview. It was about how advocacy skills can be taught to, and evaluated in, students training to work in children's rehab. In discussing advocacy in relation to children with disabilities, the term "self-advocacy" often comes up, and is held to be an ideal. The idea is that we can empower a person with disability, or give them the tools, so that they can speak for themselves. It's similar to our focus on independence as being the preferred state of being for people, with and without disability.

But there will always be some children with disabilities who are not able to advocate for themselves (because they don't communicate in conventional ways or have multiple disabilities). They need parents and clinicians and others around them to be their voice. In these cases, has a failure occurred? If my child is supposed to be a self-advocate, does it mean that as a parent I've done something wrong, or not done enough of something, if he or she isn't?

Which brings me back to our tendency to describe disability in black and white ways, to assert that it means this, or it means that, but not both. And to take such strong positions, as if we have to prove to the mainstream world that there is value in a life lived with disability.

In discussing the painter Pearce, Shakespeare says "people with cognitive disabilities still have value and can do work of value."

He says it, but as an academic, and based on some of his comments, I'm not sure he really believes it, or believes it uniformly for all people with intellectual disabilities, regardless of ability.

Rather than seeking out famous, high-achievers like Pearce, I would rather Shakespeare had taken the time to find stories that show the value of a range of people, including those whose worth could only be shown through their relationships with others, not by what they can "do."