'Travelling, side by side, through these villages of grief'

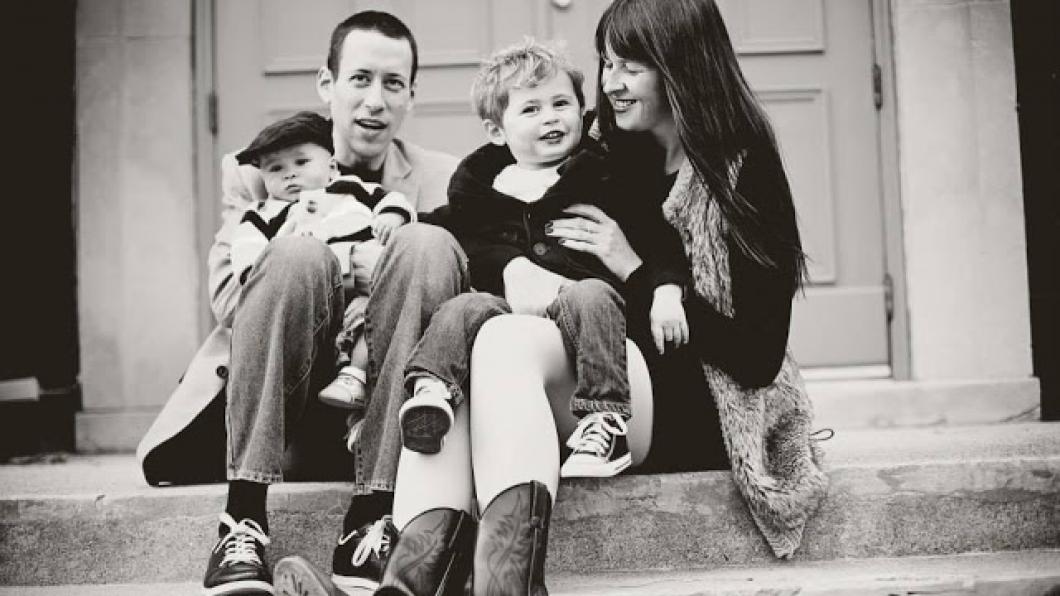

Charlotte Schwartz (above right) holds Isaiah, 4, with husband Seth and Rivers. Isaiah has a rare metabolic disease called Galactosemia, which is associated with speech and motor delays as well as seizures. Isaiah is diagnosed with autism and global developmental delay.

"My husband and I were only married a year before Isaiah was born," she writes. "We had virtually no time to just be us before we had this beautiful baby, and then everything changed again days later when he fell ill."

Here she shares a letter to her husband that reflects "how tremendously challenging having a child with various problems can be as it relates to a marriage." You can follow Charlotte at Running On Borrowed Legs or on Today's Parent: 'I worry my special-needs son is lost in the school system.'

By Charlotte Schwartz

My dearest Seth,

It's time I committed these thoughts to paper.

I feel like we've been on this road much longer than we actually have, don't you? Doesn't it seem like since forever that we've been travelling, side by side, through these villages of grief and hamlets of sorrow?

We're both so irreparably tired that all but a few things have ceased to make sense. Basic concepts are easiest for us, anything more complicated is a challenge we seem all too weak to face. I feel like we love each other, so much still, but we are silent on that subject most of the time, favouring constant action and continual, often circular motion over idling.

But I remember that there was a time—not so long ago—when our contact amounted to much more than a brushing of cracked, dishpan hands across a sink full of dishes or another e-mail exchange about Isaiah's appointments, therapies, fundraising or schooling. Indeed there was a time when "we" were the sum of our respective parts; complementary pieces in a giant puzzle and people we were proud to be. There was a time when we were both chasing dreams for our individual and collective selves that extended far beyond just getting to the end of each week.

I remember that not so long ago our lives were more than a game of schedule-checkers—arguing about whose appointment trumps whose commitment when considering Isaiah's scheduled assessments, therapies, school meetings, and life. It was full of promise; of a connectedness I had never known before, of a will to work hard for one another and to never be satisfied with less than our respective best. But now less is the best we can give.

There was a time when, just five years ago, we promised to stand by each other through whatever proverbial "thing" may come our way. We said I am my beloved's, and my beloved is mine.

But things have really shifted, haven't they? Because we belong to these boys now: I belong to my insurmountable sorrow and you belong to that place in your mind that you retreat to so frequently.

We belong to long days and erratic sleep patterns and brains that won't quiet themselves. We belong to the vice-like grip Isaiah's diagnoses have on our lives. Our options, which at one time seemed without limits, have dwindled unexpectedly. Altering the status quo could irretrievably upset the "balance" that we have worked so hard to find, ignoring how damaging that balance is to the concept of "us".

Our boy came into this world just two weeks after our first wedding anniversary; I was 28. I loved you on the day we were married but I loved you again on the day Isaiah was born. You became something new to me—a dad who I knew would do right by his son. A dad who I knew would redefine the term for me and never give up. Always being best, better.

But a week later we found out he was sick. A rare disease, no less.

No treatment. No cure.

Questions without answers, nights devoid of sleep, silent screams into oblivion and painfully blank stares that we pierced each other with. In those moments, despite our promises of abundance in love and life, we had nothing to give to the other. Nothing but silence which you needed but which felt like it was slowly infesting my life and weaving throughout my body like a poison.

Five years later, since his arrival, we still find ourselves silent often. My grief has become an immovable fixture; a hurdle over which I cannot leap, a brick wall I cannot scale. It seems it will always be there.

But as you would, you have dealt with your grief differently; like a scientist. You took your grief and converted it to an energy, a fuel. You composed an orchestral piece comprised of studies and statistics and words so meaningful that they mean nothing to so many people. You have conducted your life despite all of this, while I have voluntarily laid mine to rest. My best years, I tell myself, have come and gone. At 28, the rest of my path was forged and predictable and banished to a balancing act of maintaining composure, of being strong for everyone else, and of slowly falling to pieces on the inside and knowing, inherently, that may never be fixable.

And while I stay strong, I admit that over these last five years I have given up more than a hundred times. I've given up on you. I've given up on Isaiah, on our home, and on myself. I've given up on us, on holidays, and on some of my life's objectives. My immovable grief became so burdensome that I had no choice but to throw in the towel and accept that life had handed me lemons, and that try as I may, I don't really like lemonade.

So it's no wonder that as many as 85 per cent of parents of children with "special needs" divorce, is it? His diagnosis belongs to all four of us and because of it, in many ways, we are forced to live alone, together.

It is a life that needs two people, and two people who must be happy dividing the mundane and conquering to-do lists. It is a life where progress is so rarely made that when it is, we are cautious and apprehensive. We do not celebrate it because it may not be real.

But as I promised I would on that day we were married, when I give up, I always pick up and start again. My fatigue-driven capitulation is often short-lived and my brand of drive is renewed, if only for a while. It is in those short bursts that I can see your smile on our wedding day. I can see the hands I held at the altar. I can feel the hands on my shoulders when we were dating that were tentative and exciting. But those bursts are so painfully short; the reel breaks and we are thrust back to reality.

My dearest Seth. I am so sorry that things have turned out this way, though I know I don't have to apologize. Nothing is any one's fault. Not really. But when there is nothing left to say an apology seems an appropriate concession; when we have lost the ability to say the words we would give limbs to hear our boy say one day—I love you.

I know now that love evolves quickly and adapts to meet changing demands. Our version of love may not play out the way it does for our peers; indeed, it is almost exclusively devoted to the needs of our boy. Our love is expressed in quiet subjugation, in keeping appointments, in sending "How are you?" text messages mid-day when you know the answer will always be "Could be better." Our love's currency is reliability and sameness where all other variables are at frequent risk of changing. And if those things don't constitute love in our circumstances, then I'm afraid I know no other way.

I want you to know that though we never seem to have moments or opportunities anymore, that in much the same way I did before we were married, I gather my strength in the latest hours of the night when we retire to bed and when, for those few brief moments, you are close enough to me that I can breathe you in.

It is moments like those that fuel me more than any verbal exchange could; where so much has happened that so many words mean so little.