'There's a big appetite for creative ideas here,' scientist says

By Louise Kinross

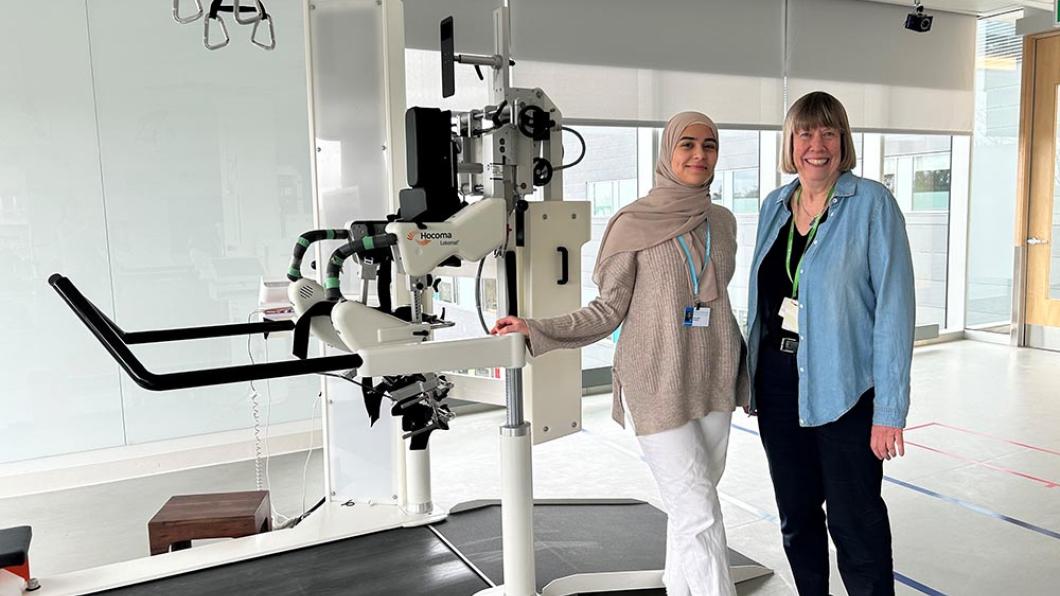

As a teen, Virginia Wright (photo right) spent summers volunteering at the Ontario Crippled Children’s Centre and Bloorview Children's Hospital.* “We spent most of our time outside with inpatient kids and even had sleepovers in tents,” she recalls. Clinicians mentored her and ignited her dream to become a physiotherapist. Today Virginia is a senior scientist at Holland Bloorview. In a full circle moment, she recently mentored research volunteer Elshaimaa Abdella (photo left), who is thinking about a career in physio or occupational therapy. We spoke about Virginia’s work.

BLOOM: How did you get into this field?

Virginia Wright: I discovered physiotherapy here at Holland Bloorview. I came as a volunteer for four weeks in the summer in Grade 10. It was the first time I’d ever met a kid in a wheelchair, because I grew up going to a Toronto school that was totally inaccessible. It was an amazing experience.

I worked with the recreation staff and we did crafts and sports and swimming in the pool. I volunteered for three summers at the OCCC and one at the Bloorview site. I noticed these kids were going off to do this thing called physio, and I got to shadow these appointments and see what was up. A very kind physio mentored me.

BLOOM: What attracted you to physio?

Virginia Wright: It gave kids a chance to work on goals that fit with things we were doing outside, and that they wanted to do. I was interested in physical stuff, and it suited my creative side and joie de vivre. I really enjoyed connection with people, and lots of back-and-forth dialogue and problem-solving, and addressing things that were challenging.

BLOOM: After studying at the University of Toronto you worked at SickKids. Can you tell us about that?

Virginia Wright: I had done an internship there and I loved working with kids. They had a position for a new grad, so I did 3 ½ years there. I did intensive care and cardiac care and a bit of new brain injury work. The physio director at the time was Sheila Jarvis (who later became Holland Bloorview’s president and CEO). She was a great boss and mentor who moved up to Holland Bloorview.

BLOOM: How did you end up here?

Virginia Wright: A job came up here and I thought rehab would be ideal for me. Acute care can be pretty high stress. And I wanted to spend more time with a child and family than just two to three weeks. Having all the acute-care skills, I felt confident in being able to handle things.

Joan Ferguson (former VP of programs and services) was my first boss. I worked in our spina bifida clinic and with the orthopedic clinic. At the time we had just started and were building our juvenile arthritis program, and I worked in it for about eight years. With children with arthritis, you do a lot of measurement. They’re changing medications, so you need to track how they’re doing. The measurement stuff we were doing was less than optimal, but more advanced approaches were being done with adults with arthritis.

I’m a mathematical person, so I got into outcomes measurement.

We wanted to work from a measurement tool that was used for adults and create something applicable to children and families. I quickly realized I had no idea of the science behind it and went to do my Master’s at McMaster University in Design Measurement Evaluation.

I kept my foot in the door at Holland Bloorview with my research while I was studying, and came back as a research physio.

We developed a self-report questionnaire for kids with arthritis and their parents to tell us how the child was doing with their physical functioning.

At that time in the 1980s, measurement focused on tracking joint swelling, pain and tenderness and range of motion. While it seems unbelievable to us now, there was a sense in the research world then that you couldn't take what a child or parent reported as accurate or valid. Ours was one of the first functional status questionnaires to allow a child and family to report on how they did things at home, at school and in the community.

Then I was invited into other areas working with children with cerebral palsy and upper limb prosthetics and brain injury. Eventually I became the outcomes measures coordinator for the whole centre. I worked with clinicians across all areas, including social work, our school and speech therapy.

BLOOM: How did you move over to research?

Virginia Wright: In 2000 I went to do my PhD in Health Research Methodology at McMaster. I was one of the first pediatric physios in Canada to do a PhD then. In 2005, I came back as a junior scientist, just as our Bloorview Research Institute opened up in our new building here. It was really hard to move out of the clinical side, but being embedded in a children’s health care centre makes such a difference. You have immediate contact with clinicians and families and their ideas of what needs to be done.

I was in an ideal spot to look at evaluation of interventions we did, such as the rhizotomy surgery and the new Hart walker orthosis for children with cerebral palsy. We developed several related outcome tools that are now used internationally by physiotherapists for clinical and research work.

Then the technology piece came on board. The first was the Lokomat, which is a robotic gait treadmill trainer. It’s for kids who are already walking, where the goals are to improve gait efficiency, quality and endurance.

I began working more with our engineers. I get drawn in to advise on how best to measure the impact of these technologies. Despite lots of work in the measurement arena, there is still an absence of measures in pediatrics that tie closely to the goals of kids and families.

BLOOM: What is a typical day like now, as you run the SPARK Lab?

Virginia Wright: I spend lots of time with University of Toronto graduate students and that’s a real joy for me. I was mentored very well here for the first 20 years, and at McMaster and CanChild, and this is a really great chance to do the mentoring and give back. I’ve always loved teaching and been enthusiastic about our profession as physios.

Many grad students are not coming with a physio background, but from engineering or biology. This may be the first time they’ve worked with children and families. As someone who was a frontline clinician, it’s great to be part of their supervisory committee, and to help guide them on conversations with families and problem-solving.

I work with engineers to design outcome measures to fit whatever technology they’re evaluating. If we’re putting a treatment into place—like we did with the Trexo, which is a robotic exoskeleton that attaches to a walker and powers a child's leg movements—we need to train a whole group of physios who have never used this brand new device. That includes a lot of direct collaboration with the students and the clinical physios. It's great fun learning together how to best use a new device within a treatment setting.

My days are very mixed. I may spend a lot of time with the study team in the technology intervention sessions. Other times it’s guiding students in their writing or analysis or work with clinical teams. I love meeting with clinicians to talk about how we’ll implement measures in clinical practice, because that’s how we get the meaning out of the research. We used to think getting interventions or outcomes measures into practice would just happen. We realize now that you have to plan it and resource it and we’re much better at doing that.

BLOOM: What are the greatest challenges of your role?

Virginia Wright: Funding. Particularly for the smaller things you want to get done. It takes a long time to get a project to the stage where you’re ready to go to the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) for big funding. It’s in those initial stages when you’re taking something that’s a clinical idea and you and clinicians decide to test it out and you need funding to do that.

My past outcomes work in our SPARK Lab has been beautifully funded by our Holland Bloorview Foundation. We also benefited greatly from additional funding support to do those essential foundational projects when I held the Holland Bloorview Chair in Pediatric Rehab from 2012 to 2022.

The other nice-to-have challenge is there are just too many great ideas one could tackle. It’s getting that sense of priority of what should we work on now, what can wait, what is time-sensitive?

BLOOM: What are the greatest joys?

Virginia Wright: The mentoring part for me. We’re working in such a great environment with people who are so committed to making the world better for kids and families. That ethos is everywhere.

I get to collaborate with so many people here, whether it’s volunteers, families, kids, students, staff from so many different specialties, and, of course, our amazing SPARK Lab team. It’s a really diverse community here that brings lots of new conversations to the table. These conversations are really exciting.

There’s a big appetite here for creative ideas. We've always been focused on the idea of possibilities.

If our team brings an idea to the table and it fits with Holland Bloorview's strategic directions and provides forward movement on things, I’ve always been super supported in pursuing it. I think that’s unusual in today's work world.

BLOOM: What emotions come with the job?

Virginia Wright: Excitement, curiosity, definitely more energy now that I’m coming back in to work since the pandemic. Even though we were connected by Zoom while working remotely, I found it lacked that physicality of being in a place where energy is bubbling up with other people.

On most days I feel a general happiness here.

I do get frustrated when papers get turned down or when students apply for programs like physio, and I know they’d be the greatest physio in the world, and they don’t get accepted. Or when we don’t get funding. Although the reality is that you regroup and work with the ideas provided by the reviewers and try again. The end result is often funding success with an even better project.

BLOOM: How do you manage stress?

Virginia Wright: I sing. I’m an alto in the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir. Singing is breathing and relaxing. It’s great for the brain because it turns a different switch on. When you sing, you have to really focus on it and nothing else. For two to three hours that’s all you’re doing.

Tonight I’m singing with the Toronto Symphony. We’re the large choir they mainly use. Our part is in German, so I’m struggling a bit to memorize it as we had three short weeks to learn it.

The other thing about choir is that it’s community. It’s this group of people that have a common intent and purpose. As our conductor says, every voice matters. You really feel you make a difference.

BLOOM: What’s the biggest change you’ve seen here in 40 years?

Virginia Wright: I think inclusion and diversity across the board, as major principles to embrace.

Also family-centred care. The number one focus here is to understand the families’ needs and priorities and joys and challenges and to really try to work what we do into those. To be there for them.

The other major change about 20 years ago was the amalgamation of our two sites and two organizations. It was a merging of two different cultures, to come together very successfully as a single organization.

BLOOM: What qualities do you need to be a good scientist in children’s rehab?

Virginia Wright: Curiosity, empathy is really important, and a love of detail. I think you need to be a really good writer and communicator. You have to have a real passion for the field and to absolutely believe that what you’re doing, in collaboration with the team, has ultimate value. If I look back at a lot of the projects we’ve done for the last 25 years, I see how we’ve had to adapt, to change with the times, and to make things current. So I’d say perseverance. Being a team player is 'numero uno'. You have to love working with people.

BLOOM: If you could give yourself advice on your first day here, what would it be?

Virginia Wright: I’d say take every opportunity that comes your way, as long as it seems within your wheelhouse.

For example, I was the interim director of research in between Colin McCarthur and Tom Chau. It wasn’t something I ever would have said I wanted as a career, but it was one of the best things I ever did. It allowed me to understand at a much bigger, macro level what goes on in the world around me, both at U of T and here. I was able to bring that back to my team, and it’s made things so much easier. It was like doing a mini MBA in a way.

Sometimes when you take a bit of a deviation from your path, it helps you to figure out your path better.

I’d also say it’s possible to stay within the same organization and have a career that is really expansive. I’ve had five to six different roles here at Holland Bloorview. As a result of that I have longevity and history of place. That stuff does matter.

BLOOM: What are your next steps?

Virginia Wright: I still enjoy the teaching and mentoring part and that’s something I’ll continue doing. I’ve got a couple of new grants right now through CIHR as a co-principal investigator with Elaine Biddiss and Jans Andrysek. I still love mentoring volunteers and undergraduate students who want to get into physiotherapy. I think back on all of the mentors and bosses I’ve had here and they’ve all been fabulous, from the very beginning right through to current.

*These were Holland Bloorview's predecessor organizations. Learn more about our history. Like this content? Sign up for our monthly BLOOM e-letter, follow @LouiseKinross on Twitter, or watch our A Family Like Mine video series.