A son shows his family the way home in Love, Hope and Autism

By Louise Kinross

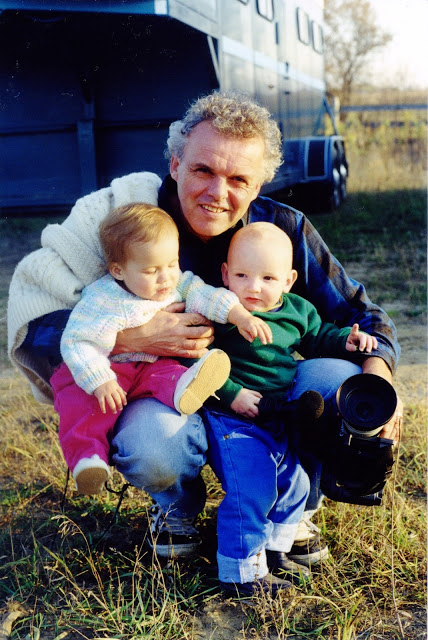

Robert Fresco is a professional filmmaker, so when his twins Fraser and Hallee were born, it was natural that he’d turn the camera on them. His exquisite home movies are the backbone of Love, Hope and Autism, a CBC Docs POV piece. The film covers the family's idyllic early days, the unravelling of Robert's marriage to Shannon Wray when Fraser is diagnosed with autism, and how the family regroups to co-parent with the addition of Shannon's new partner Tim.

'Hope' is in part a reference to Hope, B.C., the town, surrounded by mountains, rivers and lakes, where the kids lived with Robert for a couple of years. The film begins shortly after the twins’ birth in Ontario and culminates with their 21st birthday. BLOOM interviewed Shannon about what she hopes viewers take away.

BLOOM: I felt so much emotion watching this film. I pulled it up thinking I’d watch for five minutes, and I couldn’t stop. What was it like for you to watch the film?

Shannon Wray: It really evoked a lot of emotion around when Hallee and Fraser were little for me. Seeing the magic of movies, that slow-motion piece of Fraser staring at the farm, it really took me back to that moment of ‘wait, something is not right,’ and that first inkling of fear. On a certain level I wanted to say ‘no, we’re going to freeze frame here and take a different path.’ I had really profound feelings watching Fraser become autistic in the film.

BLOOM: Was it a difficult decision to make the film?

Shannon Wray: The really difficult parts of the film for me were when Fraser was lost on the mountain and his accident last summer. I had pictures in my mind of what that might have been like, but I wasn’t there, and I didn’t see it at the time. To be put back in that situation in such a visceral way was very difficult.

BLOOM: Yes, it’s unusual that you would have footage of Fraser in Emergency, but as Hallee noted, the camera was almost like a pair of glasses to Robert.

Shannon Wray: (Laughs). Until the nurse told him to turn it off.

We screened the film with Fraser recently and his responses were really interesting. He’s used to seeing footage of himself when he was a kid, but when I became emotional about his diagnosis in the film, he became very agitated and started saying ‘It’s okay, it’s okay.’ When Robert got emotional, he had the same response. He didn’t want us to be that upset.

When he saw the first frames of the waterfall where he got lost, he said ‘That’s dangerous, I don’t want to go there.’ We’ve never known where he was or what he thought, because he’s never been able to communicate it to us. He also said ‘It was so dark and I was very scared.’ When the first shot of the stretcher appeared he got up and left the room.

He came back and at the end of the film he said ‘My family all love each other.’

BLOOM: That really struck me watching the film. That the family is reconfigured, but there is still so much love. The scenes where Hallee is interviewed are very candid. Did she have any hesitation about participating?

Shannon Wray: She did a bit, but it was really interesting. After the years she spent in Hope with her dad, she became very emotionally closed off, and it was a long journey for me to get her to open up again. As we were approaching the film interviews, she said ‘They’re going to rip me open, and I think it’s time.’ She’s a very thoughtful girl. She knew she was sort of frozen up inside. and this is what it would take to get over it.

BLOOM: What do you hope viewers take from the film?

Shannon Wray: Robert and Tim and I have parented together as a pod for many years—across borders and across boundaries. Through shattered relationships, we’ve taken the shards of our experiences and put them together into something unique and loving. That’s what I wanted people to come away from the film with. That even if primary relationships can’t be sustained through the stresses of living with a differently abled child, there’s still a way to put a family together out of all of that.

The other narrative that isn’t talked about enough is how much of the oxygen was sucked out of the room for Hallee, for the sibling.

BLOOM: Were you aware of how left out Hallee felt when your kids were living with Robert in Hope?

Shannon Wray: Hallee and Fraser were the same age and quite interdependent, so on one level, because they’re twins, we always had this feeling that all they needed was each other. Something the film didn’t explore was that one of the reasons I wasn’t there in Hope was that I was taking care of my sister, who was dying of terminal cancer. I knew Hallee really needed me, but I had made a commitment to be with my sister till she died.

BLOOM: Can you describe Robert’s relationship with Fraser?

Shannon Wray: Because Fraser couldn’t latch and breast feed productively, and had really bad digestive issues, the doctors told us to get him on a bottle. As soon as he went on the bottle, Robert became his primary nurturer, because I was breastfeeding Hallee.

So Robert would sit and feed Fraser, and Fraser became more bonded with Robert, and they continued on with that bond. Then, as Fraser grew, Robert became incredibly fascinated by him because Fraser was very different. He followed him more with the camera than Hallee. What we realize now is that he recognized some aspect of himself in Fraser, too.

BLOOM: Yes, I remember one part in the film when Robert says he thinks he’s on the spectrum.

Shannon Wray: Not having to talk and be emotionally engaged at a deep level with Fraser was very freeing for Robert. He and Fraser just loved being in one another’s presence and doing things. They’d go on bike rides or canoeing. Fraser feels so free when he’s riding a bike. And he loves the quiet of the paddling in the canoe. From a sensory level it’s very still.

BLOOM: There’s a part in the film where you’re living away from the family and your young daughter calls and says her dad isn’t around and she doesn’t know where he is. Was Robert just absent-minded, or was he having other issues?

Shannon Wray: This is where a diagnosis of Asperger’s would make a lot of sense in our lives. Robert would get an obsession of some sort. That time he had seen an ad for a car he was interested in on Vancouver Island, and he left the kids and went to look at the car. It took him a few days to figure that out, during which time the kids were at home with no ability to cope for themselves.

BLOOM: Looking back, is there any advice you’d give parents about the impact of a child’s autism, or other disability, on a marriage?

Shannon Wray: When Fraser was diagnosed it felt to me like that was the time for us to really pull together, dig in and figure out what we needed to do to help Fraser and Hallee.

But Robert went into ‘Oh well, Fraser is Fraser and that’s fine. It’s all going to be okay.’ I went in to research overdrive—where do we find services and what do we do? I was trying to form a strategy about how we would get through this, and I felt very much alone.

BLOOM: I think that's very common, that people cope with a diagnosis in really different ways. I know in our family, my husband always felt I was over-reacting about things, and I always felt he was under-reacting.

Shannon Wray: Yes, one parent becomes the over-functioning one, and, as a result, the other becomes the under-functioning. They can’t figure out where to jump in. Instead of making room for Robert, I was like ‘I’m going 90 miles an hour this way, if you can keep up, hang on.’

BLOOM: How did you manage to stay so connected as a family after you and Robert separated?

Shannon Wray: In most cases it doesn’t work out that way, because so much anger and resentment builds up. One of the things I didn’t want was for my children to experience a lot of conflict between their parents. It wasn’t avoidance—I didn’t just swallow my feelings and shut down. I worked very hard to be a friend to Robert, and he worked very hard to honour that friendship, too. And when Tim came into our lives he tried to find his way into the family very gently and was very respectful.

BLOOM: Where is Fraser now?

Shannon Wray: He’s with us in Southern California in a tiny mountain village where Tim and I both grew up. He goes to school in the town at the bottom of the mountain. He’s 21 and finishes school in June.

BLOOM: Are there any program options for him after school?

Shannon Wray: No. The way that people with disabilities are managed in California is through regional centres, and the one we’re associated with is where the San Bernardino massacre happened. They manage almost 35,000 cases, and the programs are overwhelmed and underfunded. If we stay where we are, we’ll be on waiting lists, which is what happened when Fraser was little. We’re probably going to need to move to another state. If we aren’t able to commit to a job skills training program, we’re probably going to have to try to fund some sort of co-op program with other parents ourselves.

BLOOM: It’s incredible what falls on families. I know some parents are able to create businesses for their adult kids, and they devote their lives to the business. But not everyone is able to do that, for many reasons.

Shannon Wray: I know several parents who took out loans to set up a coffee shop and bakery. Their children were involved in baking, serving coffee and making and selling crafts. It was very creative. But when the parents got into their '70s, they burned out. They couldn’t do it anymore, and they couldn’t find younger people who had the desire and will to make it sustainable. There is an endpoint.

BLOOM: I understand that Hallee has agreed to be Fraser’s caregiver in the distant future. How did Hallee come to that understanding?

Shannon Wray: Hallee has always understood that she will ultimately be Fraser's caregiver, eventually. That's her choice, it's not something that we've told her she has to do. In fact, we've consistently told her that we will do everything we can to ensure that she has her own life, without Fraser, for as long as possible. The only promise I have asked of her is that she will do everything she can to keep Fraser from being in an institutional setting. Hallee was about 17 when she told us that she would be responsible for her brother.

Canadians can watch the entire film Love, Hope and Autism on CBC Docs POV.