Senate passes amended version of assisted dying bill, despite concerns from disability groups

Photo of Catherine Frazee, former chief commissioner of the Ontario Human Rights Commission

By Louise Kinross

Canadian senators overwhelmingly approved a bill to expand access to medical assistance in dying (MAiD) this week.

Bill C-7 would amend the Criminal Code to change who is eligible for MAiD. Instead of being required to face a "reasonably foreseeable death," the new stipulation is that a person has a "grievous and irremediable medical condition," which could include non-terminal disability or chronic illness.

Last month, United Nations human rights experts raised alarm about this expansion. “Disability should never be a ground or justification to end someone’s life directly or indirectly," they wrote in a statement.

"Disability is not a burden or a deficit of the person. It is a universal aspect of the human condition. Under no circumstance should the law provide that it could be a well-reasoned decision for a person with a disabling condition who is not dying to terminate their life with the support of the State.”

The experts said that normalizing MAiD for people who are not terminally ill is based on ableist assumptions that devalue the lives of people with disabilities.

Critics of the bill argued that MAiD is not a substitute for robust disability services and supports, which are sorely lacking. "I work in a world where it is possible to successfully arrange for MAiD in two weeks in an organized and efficient fashion," wrote Dr. Naheed Dosani, a Toronto palliative care doctor in this Toronto Star opinion piece. "Yet, it takes years to get the people I care for into housing, months to get them income supports..."

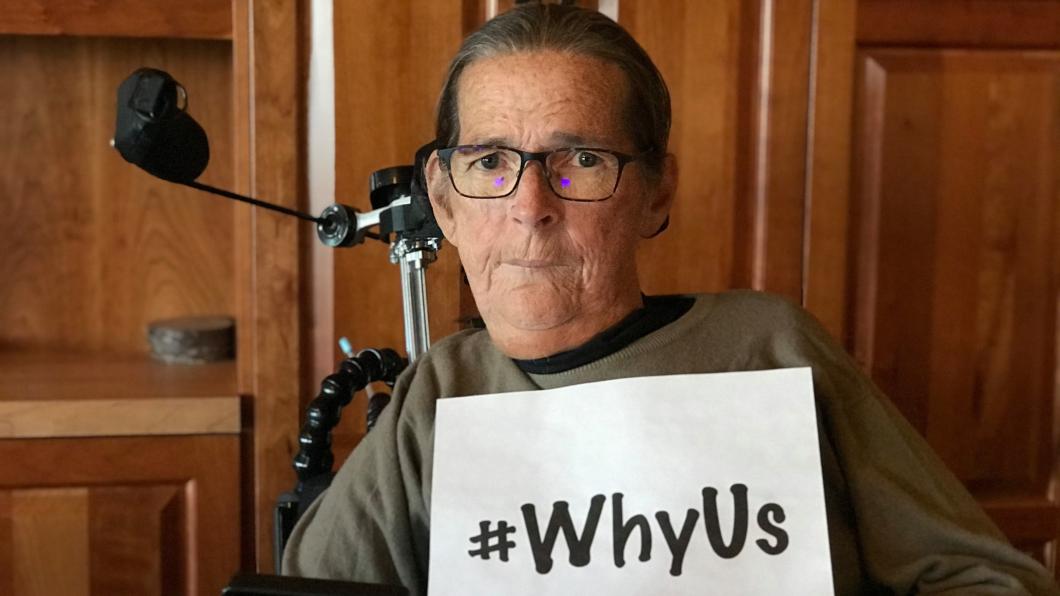

This editorial from McGill University's student newspaper raises the same concern. "In the years since its legalization, MAiD has already become a danger to disabled people," the editors wrote. "Roger Foley, who lives with cerebellar ataxia, told the CBC that 'assisted dying is easier to access than safe and appropriate disability supports to live.' Testifying to the Justice Committee for his own ongoing lawsuits, Foley says he has been denied proper care and was "coerced" into choosing MAiD because his acute-care needs were too much for hospital staff to handle.' This blatant form of ableism has only increased during the pandemic, a time when accessing care can be much more difficult, according to the Council of Canadians with Disabilities."

An open letter from advisors who created Canada's Vulnerable Persons Standard to ensure safeguards to protect vulnerable people from being coerced into MAiD asks members of parliament to rethink Bill C-7.

"Bill C-7 sets apart people with disabilities and disabling conditions as the only Canadians to be offered assistance in dying when they are not actually nearing death," they write.

"As it stands, Bill C-7 is dangerous and discriminatory. Three United Nations experts have warned that Bill C-7 will violate international human rights conventions to which Canada is a signatory. Canadian legal experts warn that Bill C-7 will violate the Charter rights of persons with disabilities. People with disabilities, including in particular those who are marginalized, Black, Indigenous, racialized and poor, have warned that Bill C-7 will undermine their dignity and put their very lives at risk."

Catherine Frazee, an advisor to the Vulnerable Persons Standard, says most of the five core safeguards in the standard "have been whittled away or completely abandoned in Bill C-7." Frazee, who has a disability, is the former chief commissioner of the Ontario Human Rights Commission and professor emerita in the School of Disability Studies at Ryerson University.

Another amendment in Bill C-7 would allow people who fear losing mental capacity to make advance requests for assisted death.

The bill would also impose an 18-month time limit on the proposed blanket ban on assisted dying for people suffering solely from mental illnesses. "The mental health amendment that will now be considered in the House of Commons basically means that 18 months from now, persons with mental illness, but not physical illnesses or disabilities, will be eligible for MAID, provided that they meet the other criteria for eligibility (18 years of age, intolerable suffering, advanced state, cannot be remedied by any means acceptable to the individual)," Frazee says.

You can read more about disability opposition to the bill at the Disability Justice Network of Ontario and Dignity Denied.