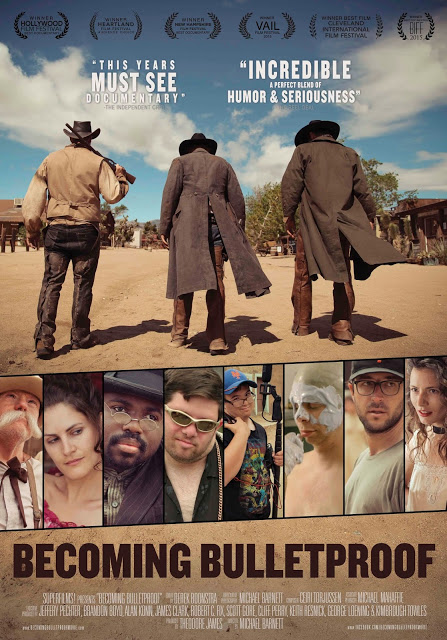

A radical idea: Be friends, make movies, respect disability

By Louise Kinross

Zeno Mountain Farm in Vermont has an unusual mission: create lifelong friendships by bringing together diverse people to make films and plays or do sports or music.

Last week 30 of these friends were in New York City for the premiere of their new film: Becoming Bulletproof.

It’s a documentary about the remaking of a 1920 Western, with a twist: its actors include people with Down syndrome and cerebral palsy as well as those without disabilities. The director and producer are award-winning filmmakers, but no one is paid to work here. And no one pays to attend. Participants come back every year. “The goal is to have these friendships last forever,” it says on the Zeno Mountain website.

I interviewed Peter Halby, one of two brothers who founded the program. What Peter has created is so radical, and so foreign to mainstream ideas about art, human value and disability, that it made me cry.

BLOOM: Why did you create the farm?

Peter Halby: We did it for our love of community and wanting to build something bigger than ourselves that would bring in a lot of the people we’ve met over the years.

I taught adaptive sports in the Boston area, my wife is an occupational therapist, and my brother is a special-education teacher. We’d worked at camps in the disability community and loved doing this kind of thing and bringing people back year after year.

We started Zeno in 2007 and said ‘Let’s take this to the next level and build a dream facility and create a lifelong network of friends that love getting together each year and having fun.’

Through my work I met wonderful people who happen to have disabilities. What was lacking in a lot of their lives was this sort of community that would be with people through their lives.

We also realized a lot of the creative stuff we all love, like making movies and sports, is enhanced with a diverse cast. It’s more fun and creatively interesting. At its core it’s friends coming back year after year doing fun, interesting things. No one is paid to do it.

Everyone is there for the same reason. We don’t have any hierarchy in our camps—we don’t even like the word ‘camp.’ It’s all about everyone contributing to the highest level of their abilities and being really honest with what people can and can’t do. But there’s no staff and no clients.

BLOOM: Do you have a background in film?

Peter Halby: We’d done musical theatre at other camps and then my brother moved out to Los Angeles, the land of movie making, so we thought we should make a film.

That first year we made a soap opera and pieced together friends in the area who would help with the film and shooting and lighting. It was a creative project we used to bring the gang together. Over the years we got better and better at it—the acting and production. For the last film we did, BulletProof, we got all the costumes from Universal Studies.

Over the years we’ve met friends who are connected with film, sound, costumes, scenes, sets, locations. When we have our movie camp in the spring, we call up everyone we know and say ‘We’re coming in, who has a connection that has a Western set? Or who knows where we can shoot a scene?’

BLOOM: How many camps do you run?

Peter Halby: We have nine camps a year and they run a week to a month long, so that’s over 100 days a year. The film camp is 2 ½ weeks. This year there were 45 of us there.

BLOOM: Can you describe the farm?

Peter Halby: Our home base is in Lincoln, Vermont. It’s a mountaintop farm with acres and acres of trees. But you can also see the Adirondacks and the green mountains of Vermont. There are six cabins in the woods. Four of them are accessible treehouse cabins. We have a big theatre barn—an ’1850s barn that we deconstructed and put back up.

The whole idea when we built the place was to make a magical place where people would want to come back year after year. The way we raised money to do our projects was through our movie premieres. People who loved what we do said whenever you get a facility, let us know and we want to help put it together.

Each cabin was donated by an individual or a foundation. We don’t get any government funding, but we do have a network of 4,000 friends of Zeno and close to 1,000 donors.

BLOOM: What’s the age range of participants?

Peter Halby: The age range is from eight to someone in his 70s. We’re open to any ability, although we don’t have anyone right now who is medically fragile. We have people with cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, autism, traumatic brain injury survivors. The mix of abilities leads to a more interesting dynamic.

BLOOM: Do you have participants who don’t speak?

Peter Halby: Yes, we have people who use assistive devices. One communicates ‘yes’ and ‘no’ with his eyes, and some smile for communication.

We have some people who need two people for their direct care and others who are pretty independent.

BLOOM: Do participants bring support workers?

Peter Halby: No, we would never have anyone bring a paid aid. It would break our philosophy of not paying anyone to come—which applies down to the cooks and nurses. People may come with a sibling, but the sibling wouldn’t necessarily work with the brother or sister or support them.

BLOOM: Where do participants come from?

Peter Halby: All over the country. We meet people through friends of friends. Part of the challenge of getting new people in is that we want to support people for life. They come back year after year. So it’s not open enrollment. We have a wait list and we can maybe have one or two new people at a camp. When someone says they want to come we say ‘We want to meet you.’ It’s a very intimate community. We want to learn about their interests and abilities and passions.

BLOOM: How do you manage to organize nine camps when you need people with very specific skills and everyone volunteers? How is that doable?

Peter Halby: That’s not the hardest part. In fact getting people to come and support us is not what I worry about. We have a huge network and people love it and in the end everyone comes for the same reason across disability: It’s community and family and friendship and fun. We’re on tour right now and there are about 30 of us, a mixed ability group, representing the new movie and we’re having a blast. We had a movie premiere last night in New York and then all went out to dinner. We’re off to LA next week.

BLOOM: What you’re doing is radical. Many youth with disabilities, especially in the high school years, are excluded and isolated.

Peter Halby: It is a radical idea. It’s a human right and a civil rights movement—the last great one in a way. And it’s so simple. It’s sad that it doesn’t exist on a major level. We hope this movie will bring awareness and understanding and acceptance to a higher level in the world.

BLOOM: What impact does your farm have on people?

Peter Halby: It’s life-changing. It’s the biggest community and family in a lot of people’s lives. It changes careers. People get married within the camp community. As an able-bodied person I take for granted the freedoms and liberties I have, and the ways I can keep connected with high school friends or any social network. I can just go out and do it. A lot of the people with disabilities that come here don’t have that human right.

BLOOM: How have your perceptions of disability changed over the years?

Peter Halby: I started working in the field when I was 15 and I’m almost 40 now, so I’ve been in it a long time. I don’t know how I’ve changed. I’ve always been in it and loved it and I love having a really diverse network of friends. I enjoy the different ways it challenges me personally—the ways I communicate with people or the different ways I connect with people. And the physical care that is involved—I enjoy all of that at this friendship level. I’ve been a teacher and I’ve been an aid. When you’re paid you can never get to this level of multi-beneficial communication and relationship. I was ‘the staff’ and that is a wall.

BLOOM: For some people with disabilities their only friends are paid.

Peter Halby: That is so prevalent in this community.

BLOOM: It seems unusual that you started this with your brother and your wives, and you all have the same passion.

Peter Halby: I met my wife at a camp similar to ours, so we came into it from outside. Will, my brother, brought his girlfriend in to the community and they fell in love with it. All of my best friends are involved.

For more than 100 days a year we’re living in the community. It’s not day trips. It’s living together 24/7. You can’t help but get really close and form really strong bonds.

When we’re making a film it’s a full-on creative project with all hands on deck. We run the camps on the premise that there is no wasted time. The one rule is you can’t do nothing. You have to take advantage of this moment, that’s the beauty of what a camp is all about. It’s focused time and energy on whatever the project is and it’s different than regular life.

BLOOM: There must be some challenges.

Peter Halby: As a director I’m constantly worried about people’s safety and making sure people feel supported and feel happy and healthy. And the logistical organizing of what we’re going to do and how we’re going to do it. Who’s going to cook? Who’s going to organize the meds? There’s so much we organize. Someone may get sick and you worry about that. But these are the smaller things compared to the bigger thing of this community.

BLOOM: In some ways our culture is becoming even less accepting of differences. How do you change people’s minds about friendship and disability?

Peter Halby: I think awareness. I think this film will help a lot. It shows everything we’re talking about in a really beautiful, incredibly well-made documentary.

The outside world has a misunderstanding of what disability is. It’s so vast and diverse and no two people are the same, just like in the able-bodied community. But people have an idea of what it is and that it’s a ‘thing’ that needs to be changed.

Even in mainstream media less than 1 per cent of disability is represented, and when you do see it it’s typically an able-bodied person playing somebody.I want a more open world. I want to see people having more diverse friends.

When you give people the time and understanding to get to know people there are ways we can all contribute and matter. That’s what happens at Zeno. Society needs to do more of that: giving people a chance to be respected and matter and have a purpose.

BLOOM: I think our readers will find this fascinating.

Peter Halby: The problem with Zeno is that we’re not an open camp. We want everyone to know about it, but it’s hard when so many people write to say they’d love to send their kid. Our mission is to support the core we have.

Ultimately, I want more camps like Zeno. We need more of these and we want nothing more than to help people start them. We would love to share everything we know and have these pop up.