Policy maker calls out racism and ableism in disability rights groups

By Louise Kinross

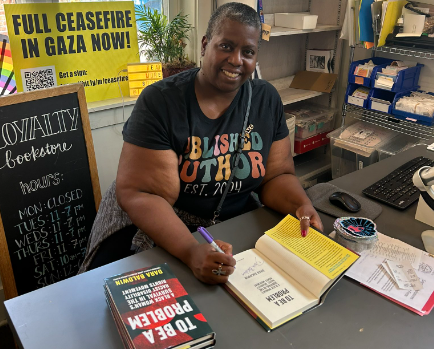

I just read a book that stopped me in my tracks. It’s about the lack of Black and brown disabled voices in America’s disability rights movement. It’s written by Dara Baldwin, a Black disability activist and policy maker in Washington, D.C. Dara has worked with dozens of disability rights groups and on over 25 federal bills signed by five presidents. In To Be A Problem: A Black Woman’s Survival in the Racist Disability Rights Movement she recounts being the only person of colour at national policy tables, and working with disability groups led by non-disabled white people. Dara herself does not have a disability. We spoke about her book.

BLOOM: When you were on task forces for the Consortium for Constituents with Disabilities (CDC), you would walk in the room and be the only Black person. You also write that only seven of over 100 CDC organizations are run by disabled people. What impact does it have when BIPOC and disabled people are not at the disability policy table?

Dara Baldwin: The book is about telling the truth and having hope to make changes. Not having representation in these rooms affects what issues are put on the agenda, what laws we go for, and how we do things.

Let’s take education equity. The top two issues for most disability rights organizations are inclusion of students and ending restraint and seclusion in schools. Restraint and seclusion is done at a higher rate to students with disabilities and especially to Black and brown disabled students.

BIPOC families have many other concerns. They’re concerned about school safety, about the school-to-prison pipeline that affects Black and brown students, the use of corporal punishment in states like Alabama and Mississippi, and having police in our schools.

BIPOC families want to see more social workers and mental health workers in schools providing more counselling. They want the system to be educational, not punitive.

They want to make sure that IDEA is fully funded, so their children can get physio and occupational therapy in school rather than families having to find it and pay for it.

Upper white middle class families have insurance to cover their kids’ therapists or can afford to pay for it. Privileged white people don’t understand what it means to be afraid of the police, and why police are not the go-to for our safety. They tend to want more police.

The voices and stories and people who live closest to the problem are closest to the solution. You can’t have a homogenous table of people and create really good social justice policy. When you don’t have Black and brown families sitting at the table, issues of importance to them are not going to come up.

Housing is another example. I’ve been on task forces that are made up of wealthy white middle class people. They’re going to be able to find housing for their family members. They can't relate to the issues of being unhoused or needing housing. They don’t worry about Section 811 vouchers, which is the program that assists those with disabilities to fund housing. The number of disabled people is growing, but Congress isn’t funding that increase. When you don’t have Black and brown voices at the table, lobbying Congress for more money to get more vouchers is not on the agenda.

BLOOM: You note that at a CCD annual general meeting, all of the award winners were white. Also, you write about how the contributions of BIPOC people have been erased from the history of disability rights in the U.S. And you mentioned panel discussions about bias and policing with only white speakers. Why is the disability rights movement so unable to see how they exclude people?

Dara Baldwin: When you deal with white people, they own the table. They don’t think there’s anything wrong. You mentioned those panels about law enforcement and juvenile justice. Their attitude is ‘We’re doing it out of compassion. We’re the smart ones, the ones with the money, we’re the ones who can get this done. Black people can’t get this done.”

When you have a white panel on bias and policing and everyone in the audience is white, there’s no accountability. When I ask ‘How can you have this panel to discuss policing and the disabled and all the people are white?,’ I’m positioned as the angry Black woman.

BLOOM: Are there BIPOC disabled activist groups you recommend?

Dara Baldwin: There are a few of them. One is NAMED Advocates (The National Alliance of Melanin Disabled Advocates) run by Keri Grey. Another is Sins Invalid. They do training and conversations around disability stuff. Keith Jones does a lot around the entertainment community and education.

Unfortunately there aren’t a lot of BIPOC groups because the white organizations keep taking most of the money. They claim to be doing racial justice work and the funders give them the money, but it's obvious the work doesn't get done, because there's no change.

BLOOM: What do organizations tell you when you ask why they don’t have more BIPOC disabled people on staff, in leadership positions and on the board?

Dara Baldwin: They say we can’t find them and it’s hard to hire them. Can you help us find those people? It’s the same excuse. It’s a cop-out. Why would you hire a Black person when the funders keep funding you? There’s no accountability until a funder says: ‘You must have so many Black and disabled people on your staff before we’re cutting you another check.” That's not happening, and why the cycle continues.

When I was at the Center for Independent Living, we had in our charter that 51 per cent of staff had to be disabled.

Being inclusive or using disability justice as a framework means having a charter or by-laws or policy that says a certain percentage—such as 60 per cent—of staff will be BIPOC disabled, and the same with the board.

I recommend we create a number of organizations that are run by and for BIPOC disabled folks. They should have a rule that for the first 25 years, which is a generation, only BIPOC, multiply marginalized disabled people will be hired in all positions, and make up 100 per cent of the board.

The key here is to have a mixture of people, so it’s intersectional. This must apply to boards as well. Currently we tend to have one or two token disabled people on a board of 20 people. And those disabled people are not in leadership positions. People don’t understand that you do what your board asks you to do. That’s where the power sits. The only way change can happen is through disruption—whether it’s political or programs and process.

BLOOM: Are white parents of people with disabilities often on boards?

Dara Baldwin: Yes, you’ll see parents on the board as opposed to disabled people.

BLOOM: In your book, you recommend a true account of BIPOC contributions to how disability laws were achieved, and a celebration of Black activists. Where can we learn more about Black voices in the movement?

Dara Baldwin: Black Disability Politics by Sami Schalk is a great book. You can also follow her on X. An article worth a read is You Have to Scream Out: What It's Like to be Black and Disabled in America in The Atlantic.

Dara Baldwin has written about why the disability rights movement will never focus on intersectionality in this piece on her blog. Like this content? Sign up for our monthly BLOOM e-letter, follow @LouiseKinross on Twitter, or watch our A Family Like Mine video series.