'Life is worth living in all sorts of bodies and minds'

By Louise Kinross

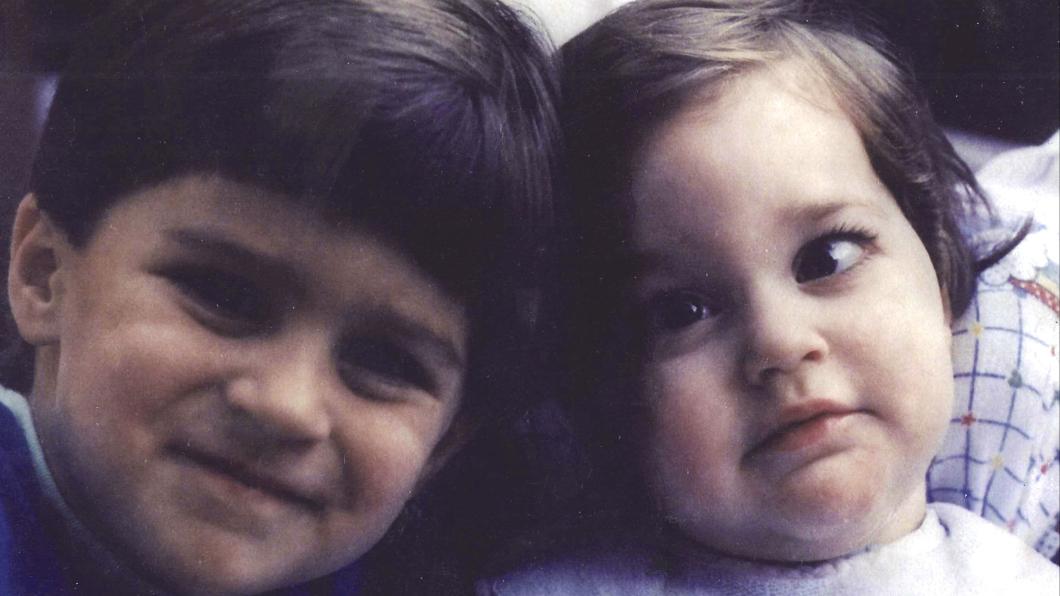

The Life Worth Living is a groundbreaking book that exposes the ableism that runs through Western philosophy and medicine, and that contributes, in the mainstream, to the idea that a disabled life is less satisfying, valuable or rich. Author Joel Michael Reynolds (photo left as a child) is an assistant professor of Philosophy and Disability Studies at Georgetown University who grew up with a brother Jason (photo right), who had complex disabilities and required round-the-clock care. Jason died in 2012 at the age of 23. In The Life Worth Living Joel examines theories of pain, disability and ability and contrasts them with the firsthand experiences of his family and others.

BLOOM: I found the title of your book 'The Life Worth Living' interesting, because typically in the media we hear about lives that aren't worth living. Why is that?

Joel Reynolds: That's a good question. In many ways I think it's because people have not thought carefully about what makes life worth living. There's a lot of fear and misunderstanding and some of that is tied to aging and some is tied to perceptions that people might lose control over their autonomy or something might happen so that they can't live the life they want.

But there's a really large body of research in the social sciences on how people respond to even very extreme changes in the way their body and mind works, and extreme changes in their social network or setting. What it shows, over and over, is that the first six months to two years is a pretty rough transition, but then people come to find new 'normals' and new modes of flourishing.

This includes not only smaller transitions, like when someone loses a limb, but it includes going from being fully ambulatory to being paraplegic and having no control from the neck down. The research finds people are very adaptive and life is worth living in all sorts of bodies and minds.

BLOOM: I had a conversation with a neonatologist who argues it's just to ration life-saving treatment for disabled newborns, particularly those with cognitive disability. When I pointed out a study where youth and young adults with intellectual disability rate the quality of their life highly, the doctor said: 'Happiness is important, but it is not the only important thing in life.'

Joel Reynolds: There's a long history of able-bodied people not believing the testimony of disabled people about the quality of their lives. This has been a problem for a long time and unfortunately still exists today. My hope in 2022 is that if someone is living the experience in question, whether they are racialized or its sex or gender differences or disability, the testimony of someone who is living the experience should be elevated, not diminished, because they are the experts. The person looking in from the outside who has not lived that life should be considered a non-expert, coming from a place of ignorance.

BLOOM: Your brother Jason had disabilities. What was it like to train in philosophy when the field has consistently devalued life with a disability? For example, Aristotle said ''Let there be a law that no deformed child shall live.' In more recent years, Peter Singer, a philosophy professor at Princeton University, has said parents should have the choice of euthanizing newborns with severe disabilities.

Joel Reynolds: It has been very challenging. I will sometimes find myself in a room with medical professionals and I know that the majority of them don't necessarily think that we should have cared for my brother and that's very difficult to deal with. But you know the sort of life I want to lead is one that defends the rights and interests of people like Jason and my mother, who is disabled through pain.

In graduate school well over a decade ago, the situation was bleaker than it is now. There are more people in the field of bioethics now who have seriously studied and engaged with disability studies and who have done their homework and are out there representing the interests of disabled people in a wonderful way. So I don't feel alone in the way I did a decade ago.

BLOOM: You write about how ableism is based on the idea that there's a standard or normal body, and anything that deviates from that involves all-consuming pain. But most disabilities don't come with constant and extreme pain. Why is that idea so persistent?

Joel Reynolds: You just perfectly stated the central question of the book. One of the conclusions I come to is that there's an even deeper misunderstanding of the nature of ability at play here. That's the idea that what someone can do at the level of their own individual body and mind is a property or characteristic of themselves, and further that what they can do automatically ties to their wellbeing in some abstract sense, regardless of context. All of that is false.

If that sounds weird, think about what happens if the oxygen in the room leaves. The ability that someone's lungs previously had becomes an inability. Whether or not one can breathe is a relationship that depends on the physical and social environment.

For the last eight to 10 years doctors have been taught that people with Trisomy 13 and 18 are 'incompatible with life' and that these conditions involve constitutive pain. All of a sudden, with advances in treatment, that's not true anymore. The life expectancy of people with Down syndrome has more than doubled since the 1950s, and it's not just because a subset of people are getting cardiovascular surgeries that they need early in life, but because of social stuff. We don't institutionalize people anymore.

When you peel back false assumptions and peel back how these things actually work you get a much more complex picture of the relationship between bodies and minds and quality of life. It's extremely expansive and complicated and rich. More often than not, people find lives are worth living in all sorts of situations.

BLOOM: I've wondered if in our culture, the word pain is sometimes code for stigma. I have alopecia, which is an auto-immune condition that results in you losing your hair. There's no physical pain or impairment. Yet when a new immune-altering drug was launched this year for alopecia, doctors and drug makers described the condition as debilitating and disabling. What's painful about alopecia happens outside the person, in social stigma. It's not okay in our culture to not have hair. It seems that if you don't have the normal body, the narrative of pain takes over, and no one clarifies whether that's social pain or physical pain.

Joel Reynolds: Everything you're saying is a sad but powerful example of how biomedicine at the highest meta levels is an industry oriented towards cure. In certain circumstances and for certain conditions, that's great, that's the right thing. But there are all sorts of conditions that come into the clinic that are topics for medical researchers where cure really in a narrow biological sense is not actually the solution, or even desired. If you think about the community of Little People, many people with achondroplasia don't want medicine to go forward so that achondroplasia goes away. They want to access wheelchairs that help them navigate the world, and they want diminished social stigma. The person who's written about this most beautifully is Eli Clare. He meditates on cure and contrasts it with care.

BLOOM: In the case of this alopecia drug, it has a black box warning for infections, cancer, heart attacks and stroke. So I think, if I'm healthy, why would I take a drug that could harm me?

Joel Reynolds: You'd be threatening your health to achieve an outcome that should be societal, and not at the level of your body.

BLOOM: You write about how disabilities can be creative as opposed to simply taking something away from a person.

Joel Reynolds: For years in disability studies and in disability activist spaces there have been discussions around 'disability gain,' a really powerful and accurate concept to capture how certain forms of disability are not simply neutral with respect to wellbeing, but enhance it or create unique goods. For example, if a person becomes paraplegic or is [born] paraplegic, their engagement in the sports community is based on the fact that everyone uses wheelchairs, and they talk about how that community is one of the greatest parts of their life.

People who identify as culturally Deaf will tell you that being a part of a community of signers is a ground for entry into all of the beautiful social things that come along with being part of a community. You can have great joy around a shared joy of community and the history that comes with it. Of course there are some disabilities, like juvenile Tay-Sachs disease, that don't come with disability gain.

Some disabilities come with disability gain, some don't, and some are a mixed bag that depends on the individual's context and situation. In the book I try to drive home an awareness and attunement to the complexity of disability experiences.

BLOOM: I liked how you described a day in your life when you were living at home with your brother and how being with him first thing in the morning was a joyful part of your day.

Joel Reynolds: I was not simply Jason's brother and often his caretaker. Jason was my best friend and the joy of being able to have him in my life is completely irreplaceable. I can't even imagine my life if he had not been a part of it.

Because of the sorts of disabilities Jason had, he visually would be seen as 'very disabled.' That's the language people would use. Yet at home, we had a system set up that cared for all of his basic needs and aside from colds or a seizure, he was very healthy. For the majority of his life he was happier and healthier than a lot of people I know who are fully able-bodied.

His caregivers talked about their lives being transformed by being able to interact with him and experience the way he took up space in the world. His life was filled with a lot of love and happiness and excitement. With disability stigma, you hear about a person who is profoundly intellectually and physically disabled and your brain immediately turns to assume their life is not good and that their family members don't enjoy being with them and that's completely false. Jason lived a life that was full, even though it was full in a different way than mine.

BLOOM: After my son was born with disabilities, I began seeing the value of presence. It's not what someone does that matters, it's their presence, but presence isn't enough in our culture.

Joel Reynolds: It's a capitalist thing. The dominant economic system in the world and in the U.S. involves engagement in the labour economy and being able to provide enough value that profit can be squeezed from it. Living under capitalism as the primary economic framework for hundreds of years has seeped into people's souls so that worth is a question of what they do, of giving back.

BLOOM: Of contributing!

Joel Reynolds: Capitalist modes of production have really messed up our vision of the value, not just of human life, but even of non-human life. It's telling to me that all of the major religious traditions East and West don't tie worth to productivity. There's intrinsic worth, whether it's by what the creator gave or something else.

BLOOM: Your brother Jason didn't speak, and speech is highly valued in our culture as part of the normal body. What did you learn from him?

Joel Reynolds: Jason communicated non-verbally. In bioethics you'll run into situations often where just because someone is non-verbal all sorts of assumptions are made about their intelligence, about what one will be able to infer. One of the arguments for doing that whole suite of [growth attenuation] surgeries in the Ashley case was that Ashley wouldn't be able to communicate pain. I read that, and I said what are you talking about?

Being non-verbal doesn't mean non-communicative. I could tell you immediately if my brother Jason was in pain and I could tell you if he had bloating or a specific pain in his back. I could read all of that off his face and body language. And just because he was non-verbal didn't mean he wasn't vocal. He was very vocal and we would make all sorts of sounds to each other that were not English words bound by syntax, but there was a rich, rich communication between Jason and everyone around him.

There are so many ways to communicate non-verbally and when someone is non-verbal the labour of the work is on those of us who communicate in normal ways to find ways to communicate. It's our narrowness and lack of imagination and openness to different forms of communication that is the problem. People who stutter report this too, and the only difference for them is that their words are drawn out a little more. They say people will not engage with them. It's sad that norms can so quickly turn into stigmas and can turn into leading people to mistreat others just because they appear different.

BLOOM: Did you ever have a time in your teen years when you felt self-conscious about Jason's disabilities? Some siblings struggle with how others see their brother or sister.

Joel Reynolds: It didn't happen in my case. For me it was the other direction where I would have friends over to the house and introduce them to Jason, and if they acted weird or uncomfortable I'd stop hanging out with them. Jason is my brother and you treat him like you would treat me or I don't want to be friends with you, period. I was very protective in that sense. Instead of feeling awkward I doubled down.

My parents were very aware after Jason was born of the research suggesting in families where there's extremely intensive caregiving that siblings can feel as though they're second priority and end up with resentment. My parents said we can't let that happen. The reason they succeeded was my maternal grandparents would come over and watch Jason whenever I had a soccer game or a musical performance, so I never felt like my parents weren't actively engaged in my life.

BLOOM: Do you have any advice for our parents in terms of siblings?

Joel Reynolds: The first thing I'd say if you're doing this kind of caretaking is you are an awesome person and thank you for being the sort of human who cares for others in that way. This isn't going to be news to anyone, but our family could not have made it without a community of other people who at times stepped up. The church community stepped up and helped and all sorts of family members helped at different points. I even had family members of friends at school that threw a fundraiser so we could get Jason a wheelchair van. That's the only reason we could continue driving Jason around. I can't possibly overemphasize how important it is to try to find like-minded people to be a support. Even if it's just an emotional support. You can't do it on your own. If you live in a rural area, try to find communities online.

BLOOM: You say that ability or disability doesn't make a life worth living, but care does. Can you elaborate on that?

Joel Reynolds: One of the things that bothers me about the history of the way people with disabilities have been treated is that over and over again, assumptions have been made about their life based on what they can or can't do. Yet example after example shows that assumptions about disability have been wrong and when we care and set up caring systems, people can flourish in all sorts of bodies and minds. This goes very deep. For me this is a political argument for why we have to have a universal health care system.

Today one in five people in America don't have access to basic health care. That is a stain on the moral character of this country. It's horrendous. You have to have systems that provide basic care. On top of that you need family and kin or a chosen family. We are hyper-social creatures. According to biologists we're one of the most social animals on earth, and in order for things to go well for us we need to set up systems with one another, in community, so that people can exist.

As the saying goes, poverty is a policy choice. Homelessness is a policy choice. Our nursing care crisis for older Americans is a policy choice. The money is there. Instead of building bombs we need to direct money toward caring for people. If I had my way we'd rewrite the core principles of America and instead of equality, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, it would be equity and care and accessibility for all. If we did live out those three values, my God, it would be amazing.

Like this interview? Sign up for our monthly BLOOM e-letter. You'll get family stories and expert advice on parenting children with disabilities; interviews with activists, clinicians and researchers; and disability news.