Instead of a mirror, blind dancers rely on their ears, feet and a strong sense of their body in space

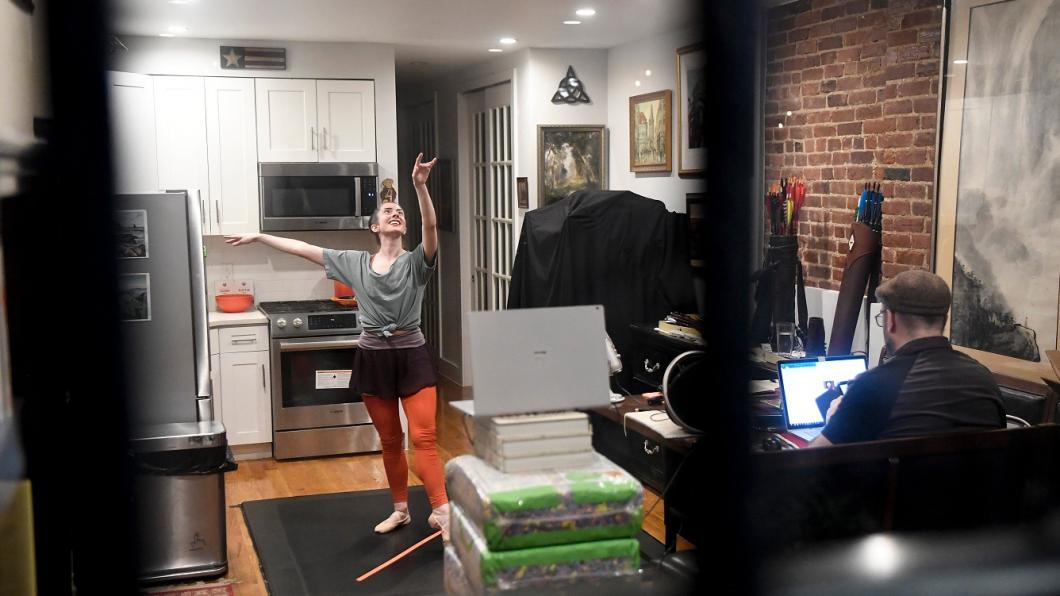

Photo © Danielle Parhizkaran – USA TODAY NETWORK

By Louise Kinross

Krishna Washburn (above) is a blind dancer in New York City who teaches a free online ballet class at Dark Room Ballet for adults who are visually impaired. Her students come from around the world. They can't see her, but they rely on her verbal descriptions of exercises and how to move their body into different shapes. Instead of a mirror, students use a strip of tape on the floor to orient them in space. Krishna is a professional dancer who has performed with many companies. She holds a Master’s of Education from Hunter College and a special certification through the American College of Sports Medicine. No experience is necessary for her introductory class, which runs every Monday night. We spoke about her non-visual style of instruction which is grounded in a deep understanding of the body.

BLOOM: What is dark room ballet?

Krishna Washburn: The concept is a system of teaching ballet that does not privilege sight. It's based on several different techniques that I've absorbed over the years. I was taught ballet through the Royal Academy of Dance, so that is the ballet style we use. I don’t give my students a mirror as a tool. Instead, I give them a strip of tape on the floor, so we have to learn with a different mindset but with the same, shared vocabulary that all ballet dancers use. It's very anatomy-based. I take a lot of inspiration from Feldenkrais techniques about coming to understand how your anatomy interacts internally, and from the great tradition of Japanese Butoh, which is also a dance style that is non-visual and very much about knowing how your nervous system works.

I have a Monday night group class at 8 p.m. Eastern Standard Time, and I have students who come from every part of the world and every time zone. My students mean so much to me. Monday class is open level so it's suitable for people with an introductory level understanding of ballet positions. We typically do six exercises, including centre, and I use very fun music. I speak and describe continuously through the music. Some of my students have some sight, but most of my students don't see me at all. The first hour is focusing on being in your body and ballet technique. The last half hour is the most important part, because it's question and answer time. Students can ask me to explain something we did in more detail so they're clear on it. It's also a time for the blind and visually impaired community to get to know and support each other in their dance journey.

BLOOM: Why do you call it dark room?

Krishna Washburn: For many reasons. A dark room in photography is where images develop, so the dark room is also a theoretical place where you as an artist take time to develop and allow yourself to change chemically.

BLOOM: I love that analogy. How is blind dancing different from sighted dancing? I read this on your website in a piece called Breaking down stereotypes about blind dancers: Some people, even other disabled people, think that the aesthetic of the blind dancer is basically what a sighted dancer would do, just not as good. This is a mistake that people make because of ableism. A highly skilled blind dancer is absolutely not lesser than a highly skilled sighted dancer, but is, indeed, different.

Krishna Washburn: That essay is about breaking down stereotypes about blind dancers and taking the fear away from talking about ableism. When we talk about the difference between how a sighted and blind dancer moves, it’s really very different, because we need to think about our bodies and our movement choices very differently. We have to use our ears, use our feet, use our sense of internal orientation, and we need a much greater awareness of our own anatomy.

The study tool of the sighted dancer is the mirror. You watch your teacher in the mirror and copy your teacher. The blind dancer can't do that. The blind dancer has to understand the floor, that is our tool. We use a tape strip. The orientation tape on the floor is a very old tradition. It's how blind teachers teach blind students how to keep their spot as they're studying, how to keep their sensitivity in their feet, how to understand where they are, and how to feel confident where they are. I need to understand where all of my bones are in my body. Maybe a sighted dancer doesn't have to do that. I need to know exactly how much space I have before I begin a choreography. A sighted dancer doesn't have to think twice about that. That doesn't mean that the quality of my artistry is in any way secondary to what a sighted dancer does. I'm not compensating. I'm using technique that is appropriate to me. I'm a master of my art in the same way sighted dancers are a master of theirs.

I feel there's a very unhealthy narrative we teach to kids that you have a disability so you're going to have to overcome that disability and compensate in order to achieve what you want to achieve. That's a terrible thing we teach our kids. It doesn't reflect reality. The reality is we live in an ableist world. I've mentored younger, pre-professional dancers who've told me 'I thought I needed to compensate or work harder or do something to overcome.' We need to be frank. There is a problem in our culture called ableism. People think what you do is less valuable and less important than what non-disabled people do. And that isn't true. When people discriminate against you and use stereotypes about your disability, instead of interacting with you as a unique person, we need to point it out, or get an older person to help.

BLOOM: What’s the greatest challenge of doing your class online?

Krishna Washburn: The hardest part is making sure my technology is not going to break, because that has actually happened. The compressor in my extremely expensive microphone did break and we had to do old school and use the internal microphone in my laptop. But I got a new one right away. So you have to make sure the technology is your friend.

I love teaching online because I don’t have the commute. I didn’t even realize this but prior to quarantine, I spent an easy four hours a day in the subway in New York City, getting to studios. I have so much more time now and I work so much harder. I'm doing many private classes as well as group classes, and I'm rehearsing in arts projects and creating art on my own.

BLOOM: What's the great joy of your online class?

Krishna Washburn: There’s so much joy. Having conversations with my students in Q and A time, when you can hear in their voice that something clicks. Ballet is fundamentally a dance form that prioritizes balance. You stabilize one part of your body so you can have freedom elsewhere. Most of the time you stabilize your torso, so your arms and legs can move freely. Once that clicks, and the student says I know how to find the back of my heels, to transfer my weight from foot to foot and keep my torso stable so my legs can move as I want, and I can feel balanced and not feel scared, then every movement from then on is like the first domino falling on the floor and the rest fall into place.

BLOOM: What do people, especially beginners, say they get out of the class?

Krishna Washburn: A lot of blind folks have been deprived of information about their own bodies because somebody decided that because they’re blind or visually impaired, they don’t need to know about their own skeleton, about their own nervous system, and about the names of the parts of their body. I've had conversations with adaptive physical education teachers who work with young people, and I always encourage them not only to always use their voice and describe movements, but to explicitly teach anatomy, even to little kids. A lot of blind dance beginners who are adults need this education, and there aren't people offering it to adults.

If I'm starting with someone who has been prevented from knowing the basic facts about their body and their body’s capability, I'm giving them the opportunity to truly take ownership of their body and to know what it is and what it does and what it can do, and to not feel anxious about movement. I want them to feel happiness in movement and to feel freedom in movement and to not feel the weight of judgment of sighted people watching.

BLOOM: How did you get interested in dance?

Krishna Washburn: I started out as a sighted person who was scouted by the Royal Academy of Dance when I was three. I went through the entire curriculum and it wasn't until I was a young adult in a pre-professional stage of my training that I experienced vision loss. All of my paid work has been as a blind performer.

BLOOM: I know you perform with a number of dance companies. What pulls you to teaching?

Krishna Washburn: I was born to be a teacher. That's always mattered to me. And I don't want what I've learned in life as a dancer to die with me. I want to grow this as a field and gain legitimacy and not become a separate group that no one has heard of. If you're American, it's very normal for you to have dance lessons as a kid. Unless you're disabled. I would like dance to be a normal part of growing up, whether you're disabled or not. Every child should have a chance to learn about the body and take time to understand these are how my bones feel together, and I can feel the nerves in my fingers and feet, I know they’re there. It's not theoretical stuff from science class, it’s real.

BLOOM: What is the best way for someone to contact you if they'd like to consider joining your Monday class?

Krishna Washburn: Just e-mail me at info@darkroomballet.com.

You can learn all about Krishna and her classes by visiting Dark Room Ballet.