How a family that shares a genetic condition creates a vision

By Kenneth Springer

I’ve been pondering what to write for BLOOM given that I’m a parent with a disability and have two children who have inherited the condition from me. It’s not often a parent can tell their child that they completely understand what it’s like to have their diagnosis and mean it. After all—unless you share the condition, how would you know?

When told your child “isn’t normal,” parents may react differently, whether it’s shame or fear of the unknown or guilt or even disappointment and resentment. What will others think? Does having a child with disabilities reflect back upon us parents? Whose fault is it? Will we be judged and mocked? What happens now?

In my case, I skipped the above and was faced with one question: should I have children? I already knew firsthand some of the challenges they’d face. I’d tasted the pain of being different before they would even discover what being different means. In essence, I would see myself mirrored in my children.

The arguments for having or not having children went around in my head like some complicated paradox question that has no answers. To not have children because I feared passing on the condition meant I was denying my life’s existence and concluding that my experiences weren’t meaningful or valued. That is nonsense, because I’ve been lucky and blessed in many ways: I have many happy, cherished moments and I found and live with the love of my life. Yet to pass on a condition that will fill my children’s lives with challenges might be considered unfair, particularly since I hadn’t fully accepted my own differences at that time.

In the end, I trusted that if the children had a life similar to mine, walked a similar path and found love, then it would be worth it. I convinced myself that if I shared my own experiences with my children then they could leverage my past and do more than what I have done. Perhaps it was that I believe in hope or fate.

For the record I’m legally deaf and have an extremely rare congenital condition called Craniometaphyseal Dysplasia. CMD is a skeletal disorder that can cause mixed hearing loss, vision impairments, facial changes due to bone thickening, and other complications. In some extreme cases a shortened lifespan is expected. I wear hearing aids and rely on the little hearing they provide and lip reading to communicate.

My children, first Elleleen and two years later Huey, inherited CMD and both are hearing impaired. Their early development progressed well thanks to my wife Eileen who ensured their learning included social and educational development. This was a plus for me because although I’m a high achiever, I was a shy person when young. Being shy was often a bigger obstacle for me than having the disability itself. I didn’t want my children to face that obstacle. Shyness is a symptom of being uncomfortable with who you are. This is made worse when it becomes a habit. As parents, we need to ensure that our children are confident with themselves as individuals. Having confidence is necessary to excel in life.

At the age of four, Huey became extremely sick. Huey had pain as a result of fluid buildup in his head. The doctors questioned how he had such a high tolerance for pain and why he was even alive. Immediate surgery was required with no guarantee that he would survive. If he did, the surgery might leave him with a brain injury.

But doing nothing meant death.

Miraculously, Huey survived the surgery but lost his eyesight in the process: he became totally blind in one eye and legally blind in the other. Memories of that time still feel raw and painful, especially the realization that Huey would be hearing impaired and legally blind. Given the massive lifestyle changes required to cope with blindness, my wife quit her job to care for our son.

For the first time in my life I was fearful and worried for Huey’s future. What would his future employment prospects be like? Would he be able to earn a living and be independent? All of the hopes that I had for him were dashed.

Naturally, my wife took this setback very hard. This made her more determined to ensure that the children had a strong foundation that would enable them to do what they wished in life. She encouraged them to stand up for what they believed in and to participate in activities and enjoy life.

Gradually, Huey put the family back on track with the return of his bubbly personality. Yes, life had changed, but the process of facing challenges and finding a way through them hadn’t. Huey learned Braille and how to adapt in a world he couldn’t see. As a family, we learned with Huey and supported each other.

One of the disadvantages of having a disability is that you’re constantly underestimated. People expect the worst from you and conclude, for the most part, that you are hopeless, have no value and won’t amount to much. I’ve always hated this attitude. As a result, I never wanted to quell my children’s ideas or feedback.

Rather than stomping out weak ideas or rejecting others based on a difference of opinion, I found it better to be open-minded. I encouraged my children to explain their way of thinking and to debate ideas fairly. As a result, I found I was always learning from them. When I don’t understand their logic or reasoning, I try to understand why. I think this was pivotal in our children’s development.

For example, Huey was interested in learning to use the computer because he wanted to be like his older sister. Unfortunately, because he can’t see he struggled with web browsing accessibility.

The web is very visual in nature. Sighted people generally develop skills to skim over information of little value and quickly extract what is relevant. This improves with the familiarity of the web page layout.

We all have different ideas as to what works best.

A blind person prefers information structured in a way that enables them to find it quickly. The aesthetics offer no value and may make things worse if they can't find the button they need on that page. People with autism may prefer to have information presented in a simple way so that they aren’t overwhelmed with a flood of information and colour.

One day when Huey was nine he got frustrated and listed everything that made it hard for him to use the Internet. Then he suggested how it could be improved. He wanted to be able to control, categorize, filter and select just the information he wants. In reality, Huey was suggesting an idea that I considered to be impossible: the ability to display websites in a way that match a user’s preferences for how information is displayed and interacted with. This would make web browsing easier, smarter and even fun, with you in control.

I’m a computer engineer, but Huey was explaining the Internet to me in a completely new way that was eye-opening. It seemed impossible, but I couldn’t dismiss his ideas. I was compelled to learn more. I researched within the community and found that accessibility issues were prevalent and Huey wasn’t alone: many people were struggling with this.

It soon became evident that to overcome the problems we needed to be more visionary than the current accessibility standards.

So we started a project called Hueyify. Hueyify is a software that allows you to control the way web content is displayed and the way you interact with it.

We’ve been working on the Hueyify project for more than two years now and every day we tackle the challenges and work through the stages of moving towards the goal of helping those who need it. Hueyify will be free for anyone who is legally blind or autistic worldwide.

Being a key part of this project has helped my children feel valued. They’ve each contributed ideas that have built their self-worth. From my experience, having self-value counteracts the negatives from disabilities.

In raising my children I’ve found that learning is a two-way street. I learn and develop along with my children.

I’m always sharing experiences with my children, whether it’s the way I was confronted with a new challenge or how someone reacted to my condition.

Often my children will suggest what I could have done differently, or tell me something isn’t worth worrying about and that I need to see the funny side of things.

My children’s acceptance of CMD taught me to find my own peace within myself. My children are truly my teachers.

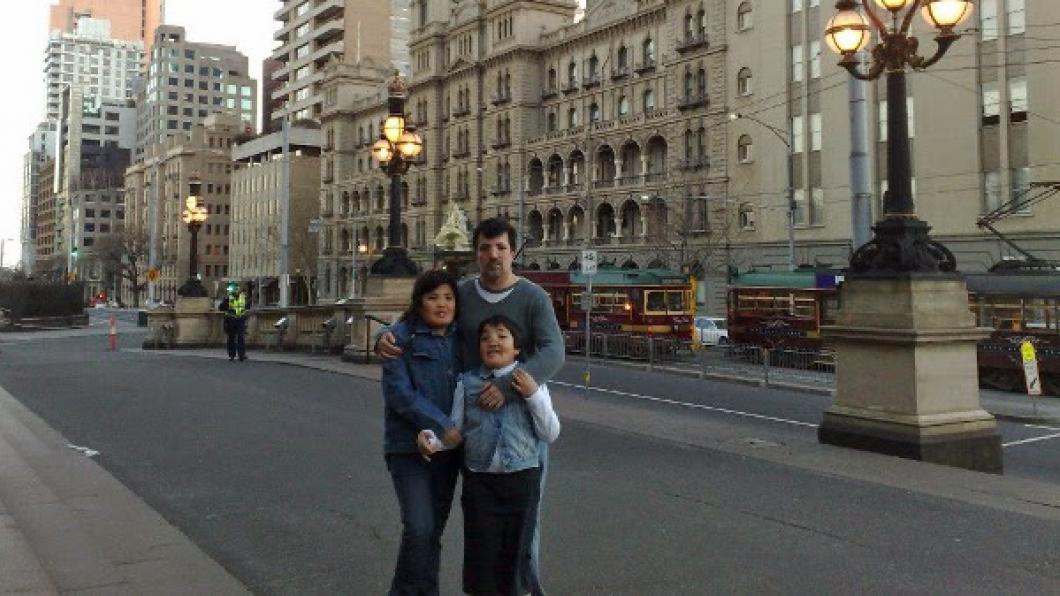

Kenneth Springer is a computer engineer who lives with his family in Victoria, Australia.