Disabled boy finds his inner ninja

By Louise Kinross

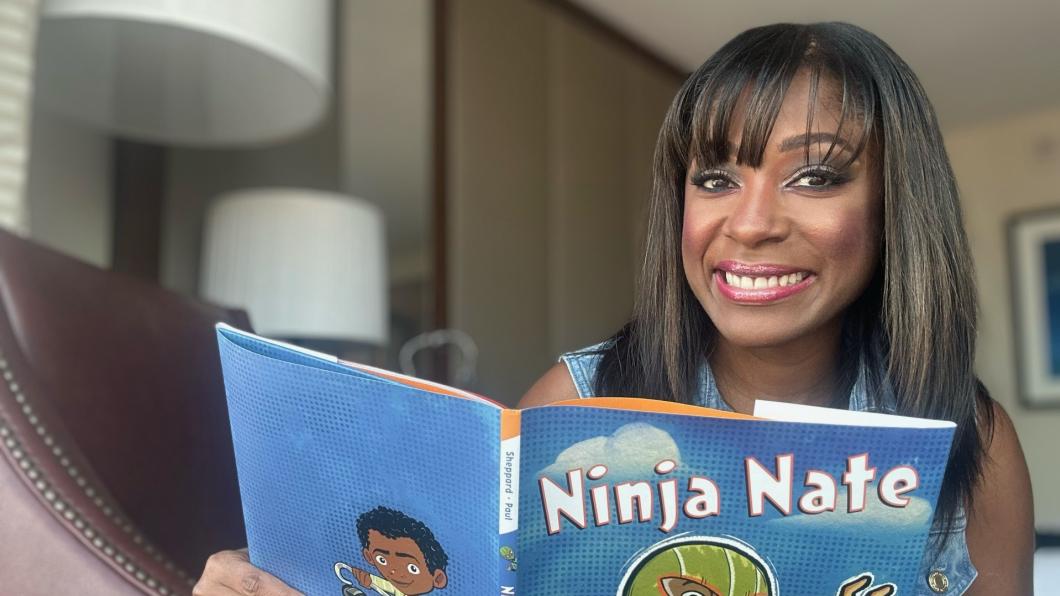

In Ninja Nate, a 10-year-old boy called Nathaniel Brown wears his ninja suit and carries his sword everywhere. But underneath, he's hiding a big change in his life: he wears a prosthetic leg and uses a cane. We interviewed author Markette Sheppard, who lives in Maryland, about her picture book geared to kids aged four to eight.

BLOOM: How did you get the idea for this book?

Markette Sheppard: I have a 10-year-old son who loves ninjas. When I wrote the book, I happened to be reading a story in The New York Times about a family of five cousins who lived in the Middle East in a war zone. They were playing soccer one day and one of the kids stepped on a land mine and all five children lost a limb.

A reporter followed one of the children who had lost a leg at the hospital. He learned that in his dreams, the boy had two legs. He would wake up and forget that he'd lost a limb and jump out of bed and fall. My heart sank as a mother, and I thought how can I teach children about empathy?

The story stayed with me, and I wanted to incorporate a subject children love, so it's not didactic or academic. My son loves ninjas. At some point he'll work with someone who is disabled, or have a classmate with a disability. I thought how do I introduce this concept to him?

BLOOM: Why did you want to tell the story of a child who acquires a disability, which is different from a child who is born with a disability that becomes part of their identity?

Markette Sheppard: It's about self-acceptance. I don't detail in the book what happened because it's about the journey towards: 'Am I going to assume this alter ego of Ninja Nate for the rest of my life, or am I going to be who I am?' Most times, I feel like children are accepting, but adults who haven't been exposed to different types of people have a harder time. By introducing new concepts to children I feel like I'm putting goodness into the world. I'm helping raise a generation of readers who are accepting of all kinds of people with different abilities.

BLOOM: Nathaniel is worried about how kids at school will react on his first day back. What does he learn?

Markette Sheppard: He learns that once he makes the decision to accept himself, everyone else will follow. We all have to be leaders in our own hero's journey. Throughout the book, no one is telling him he's not Ninja Nate, and that his sword is actually a cane. We understand when he falls out of bed that the dream is over, the bubble has burst.

BLOOM: His school friends are very accepting. Is that realistic?

Markette Sheppard: I really think so. Kids are more open-hearted in that way. That's how I've seen children react to disabled children. I'm a den leader in my son's cub scout pack. We had a cub scout with severe disabilities who joined us two to three years after the core group had been together. All the kids were like 'We have this new kid, he's cool. He has this tablet we can talk to him on.' They never asked anything about his health issues, they just saw him as a new playmate with a different, cool way of connecting.

BLOOM: What do you hope readers take from the new book?

Markette Sheppard: I hope it came across that even though Nathaniel Brown is pretending to be Ninja Nate, everyone around him, including the kids at the playground, knows about his new disability. I think they know the journey to self acceptance is one you do in your own time, and that Nathaniel will reveal his robotic leg when he's ready. That's okay, because people need to process things.

BLOOM: There's often a lack of Black voices in books that touch on disability. We just interviewed a Black American policy maker who wrote a book about the racism she experienced in her work with disability rights groups. Why is it important that Black disabled children see themselves in books like yours?

Markette Sheppard: As a Black woman journalist, I have a lot of experience with what that policy maker talked about. I started out as a digital journalist and then a radio reporter and TV reporter.

I remember as a radio reporter I was at an Occupy rally in DC. It was outside municipal buildings where they were calling for more social services and economic justice. I was covering this story and speaking to leaders of the movement, and I had recently had abdominal surgery. I was very weak, and I found a chair to lean on as I did my interviews.

One of the leaders who was a Caucasian man pulled the chair out from under my knee and handed it to someone else and said 'Here, do you need somewhere to sit?' I didn't know whether it was because I was African American or because I looked healthy, but I couldn't stand for long periods of time.

I started up the interview and the same person looked at me with shock on his face. He didn't realize I was the NPR reporter. They knew a reporter was coming from an NPR affiliate in Washington, but he didn't know that I was that reporter.

In that moment you can't say anything, because it happens so much. The blatant disregard for your humanness. I know as a Black woman going into spaces in an industry that's not dominated by other Black woman, you do feel a difference in how you're treated.

I think Ninja Nate can help disabled children of colour through its mere existence. 'There's someone who looks like me going through what I'm going through. I'm not the only one.' That's comforting.

Ninja Nate can be borrowed from Holland Bloorview's library. Like this content? Sign up for our monthly BLOOM e-letter, follow @LouiseKinross on Twitter, or watch our A Family Like Mine video series.