'Disability was home:' From big sister to anthropologist

By Liz Lewis

There's an old adage among anthropologists that you have to spend time in another culture to truly understand your own.

As an undergraduate researcher in Ghana, I knew I'd encounter different practices and beliefs about disability, and see firsthand the struggles of people who lacked basic resources.

I remember vividly the first time I saw adults with physical disabilities crawling on sidewalks, flip-flop sandals positioned carefully on their hands and feet to protect them from the rough ground. I'd been told about this and even seen pictures, but the image still shocked me.

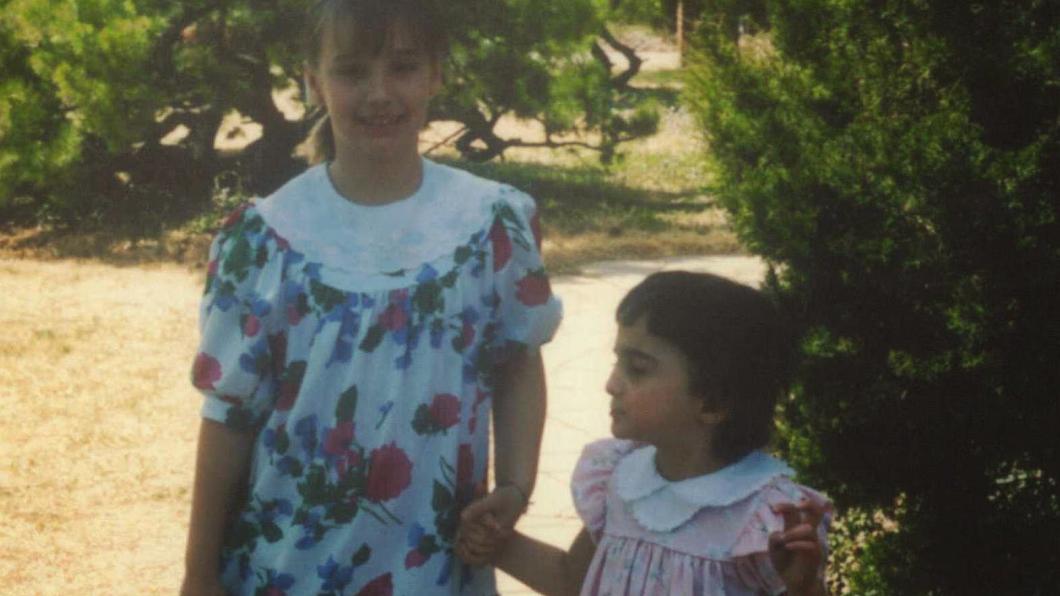

It was my first experience of "coming home" to disability after growing up with a younger sister, Katie, who has multiple disabilities and is deafblind (see photo above).

Three months into my study abroad program, I embarked on the independent research portion of the curriculum. My study could focus on virtually anything that appealed to me. Pushed by my parents and encouraged by a family friend who was an international disability expert, I had been careful to set everything up in advance for my short-term project on blindness and social stigma. Our friend’s stories of working on deafblindness issues in Asia and Africa dazzled me, and I was curious about following in her path, even for only a short period.

On the first day of my project, I hopped a taxi from my temporary home at a local hostel to the office of the Ghanaian Association of the Blind. It was rush hour and Accra’s streets were packed. People selling gum, cigarettes, and compact discs wove their way between stalled traffic at lights, along with children and adults begging for money. It was here that I first saw adults with physical disabilities crawling on the sidewalks.

I arrived at the Association of the Blind and tried to make my way through the complex in search of the appropriate office. As a 21-year-old white American woman, I stood out. People were curious. Two men in their 20s approached me. They were not verbal, so they began signing to me. Although I did not understand most of what they said, we all grinned widely as we tried to communicate across the layers of barriers. They led me around the facility to the office where I was to meet an internationally respected disability expert, and we said our goodbyes. I recall a feeling of utter naturalness and comfort. It hit me: I was in the right place, in every sense.

This was the first time I truly felt the universality of my position as a person who grew up in the disability community. Until then and, indeed, for many years after, my feelings about disability in my professional life were marked by ambivalence. While part of me perhaps always knew I would end up dedicating my career to disability issues, I was reticent – scared, even – about committing. Was I really ready to welcome disability into my work life, since it would always be a fixture of my personal world? And, if I didn’t want to be a special education teacher or service provider, what could I possibly do?

I had been immersed in the disability world since the age of four, when my sister was born. Although we did not know it for many years, Katie had CHARGE syndrome, a rare genetic condition found in about one in 10,000 births. I grew up surrounded by children with disabilities and their families. I visited the local parent resource centre with my mom, helped my parents flip through binders of special-ed law during our struggles to obtain appropriate school services, and I accompanied my parents on countless visits to doctors, specialists, and therapists. As the older sibling, it was my job to help and I took pride in it.

Still, as is typical, I became less involved as I got older. I was busy with high school stuff – classes, extracurriculars, and friends – and then I went away to university. My love for Katie was unwavering, yet I noticed a growing public-private divide in my relationship with disability. It had become something that was confined to my family life, but my academic and personal realms were increasingly separate. Or were they? Although I felt that way at the time, looking back I can see clearly that I flirted with disability issues as a vocation throughout college. I simply wasn’t ready to commit, nor did I know where I fit in.

During my semester in Ghana, I was shocked by the level of interest among my peers and professors regarding my research. As a sociology and anthropology major, I had no idea that disability was even a viable area of study. I didn't know of any scholars in traditional academic areas who focused on disability, nor had I read or even heard of any books or articles on the topic. While gender, sexuality, and race were fair game in terms of identity politics, disability somehow remained in the shadows. Even if I’d been ready to pursue an academic career researching disability, I did not yet know it was an option. I had no models.

In the years that followed, I largely forgot about disability outside of my family life. I worked abroad briefly after graduation and then returned to the U.S., where I embarked on the typical life of many 20-somethings. I lived in a large city filled with countless restaurants and bars, worked diverse jobs of various interest levels, hung out with my friends, and met the incredible man I would later marry.

For the first time in my life, I eschewed all things serious. I didn’t even do volunteer work! And I was totally and utterly bored. Young and relatively mobile, I took my meagre savings and moved to South America in search of more. After a position as a preschool English teacher in Ecuador ended, I wandered down to Bolivia in search of volunteer work and adventure. I began helping out at a residential centre for children with disabilities – many of whom had been abandoned – and also orphans. When I first toured the facility, I once again encountered that unmistakable sense of knowing. Disability was home.

The experience opened my eyes in new ways to disability realities I had not encountered. I saw multiple children whose disabilities – physical and intellectual – were inseparable from abuse in their former homes. Most of the kids never learned basic living skills, much less anything academic. Well-meaning and overworked staff, many of whom were just teenagers themselves, tied children to wheelchairs to keep them in place.

I will never forget the day that my now husband, who was with me, realized that his favourite student could walk with assistance and did not need to stay in her wheelchair. Little Magdalena, who was known for giving wet, sloppy kisses on the cheek, spent her mornings over the weeks that followed dancing with my husband. She loved him. We marveled at her secret abilities and wondered what else she might have been able to do with adaptive technologies, educational funding, and family and community support.

I came back to the U.S. with a new sense of direction. I began an interdisciplinary Master’s degree program and promptly fell in love with a class on the anthropology of disability. I had not known the topic even existed! Finally, I was exposed to disability studies literature, as well as social science and humanities approaches to disability. I was hooked. I read everything I could find, wrote a thesis about parent advocacy efforts, and set out to find my dream job in disability. Unfortunately, it remained elusive and I wandered elsewhere, dedicating myself largely to issues of education, migration, and human rights. As always, I was drawn in by the individual faces and stories behind broader lived experiences, yet I had little interest in working my way up a nonprofit ladder. I wanted to stay in the thick of it, to immerse myself in life histories and absorb everything people would reveal. After years of fighting it, I gave in: it was time to get a PhD in cultural anthropology.

Five years later, I can finally say that my old ambivalence is gone. I have immersed myself in the formal study of disability and am pleasantly surprised by the support I have received from the academic community and beyond. I spend my days reading, writing, and talking about disability issues, and I am lucky to be involved with some fantastic local organizations. I have conducted research in Central America and the U.S., presented papers at multiple conferences, and I am in the process of writing a dissertation on family experiences with complex diagnoses.

Every aspect of my work is informed by my own experiences as a sibling, and I am honored and humbled by families’ willingness to grant me a small window into their stories. I feel so lucky to be part of a nascent but growing group of social science and humanities scholars working in the area of disability. I am also steadfast in my commitment to generating scholarship that reaches beyond the walls of academia. I hope that my work will be read by families, organizations, professionals, and policy makers. As a sibling-researcher, these are not abstract aims. I literally think about them every morning as I sit down to write or each time I meet with other families. These goals animate every step I take.

I still do not know how I fit into the dominant perceptions of what it means to be a sibling of someone with disabilities. My parents were warned when Katie and I were young that I would likely be jealous or resentful of her, since she would receive so much attention because of her disabilities. This always struck me as ridiculous, even as a child. Did experts really think that I was selfish enough to resent my parents’ attempts to find new therapies or educational techniques?

Another concern was that I might develop so-called problem behaviours and act out in response to our family’s struggles. In reality, I never felt like that was an option. My family had our hands full and simply didn’t have room for me to do poorly in school or get into trouble. As an adult, I am not convinced that this pressure was a bad thing. Did I miss out by pushing myself to make good grades and not get caught up in boys, partying, or risky behaviours as a teenager?

The discourse on siblings still hinges on a curious paradox: whether we are too good or too bad, we will still be pathologized. Our behaviours are all too often explained in terms of our sibling status. This is an extremely problematic gap in understandings of who we really are as a diverse group of individuals with different goals, anxieties, and hopes, who happen to be unified by our sibling status. Can I explain many aspects of my personality in terms of my experiences with Katie? Yes, but that doesn’t make those explanations correct, nor does it reveal anything about how I might have turned out in a different family context.

Even today, I struggle to express my childhood feelings about Katie’s disabilities for one simple reason: Katie was normal to me. I knew nothing else and, even in the earliest weeks of Katie’s life, when we did not know if she would survive nor did we understand the complexity of her intellectual and sensory disabilities, I was fiercely proud of her. She was my sister. She was the only sister I had, the only sibling relationship I would ever know.

As I prepared to enter high school, my family became involved in a heated dispute over Katie’s educational rights. I do not recall speaking to any of my friends about it until my final year of school, but that silence was part of a broader social protocol. My peers and I restricted our conversations largely to things like boys, clothes, and gossip. I later learned that some of my friends had faced serious family struggles during that time – addiction, mental illness, infidelity, violence – yet we didn’t discuss these experiences until much later. Perhaps disability had less to do with my silence than I used to think.

Even at the peak of my family’s legal battle to meet Katie’s educational needs, the only profound feelings of sadness and anger I had were directed toward the failure of the institutions we relied upon to meet our needs, not Katie. The key is that these needs were all of ours. I learned early that the perfect families depicted on television are nothing but fiction, and in reality we all have our struggles. I realized, too, that we live in a world in which people are literally cast aside. This was probably the hardest thing to process as a teenager, and I recall a palpable sense of grief for the naïve optimism I saw in many of my peers.

Still, the biggest emotional struggle for me as a teenager was my lack of a network of other siblings to relate to. Not only did I have no one to talk to who could truly relate to my experiences, but I had no models. This was before the days of Facebook and disability listserves, and I would not learn of sibshops until years later. The only sibling support groups in our area were for brothers and sisters of kids with autism, so that didn’t work. Without anyone to follow, I simply did the best that I could. I winged it. Once I began college, I made an explicit effort to open up about my experiences with Katie from the start. I learned very quickly that people were genuinely interested in hearing our story, and my previous silence was broken.

Looking back at my circuitous path, I should have known that I was a researcher at heart. My passions are meeting families, hearing stories, writing what I see, and sharing these powerful disability realities with people who might not encounter them otherwise. My aim is, and perhaps has always been, to get the word out. I want to learn, witness, and disseminate.

I want to be part of a small, but growing, effort to push disability from society’s margins and into mainstream discussions. I want to do everything I can to make sure that other siblings do not feel as isolated or singular as I did when I was younger, and to encourage scholars and journalists to take disability seriously – not as an object of pity or a source of stigma, but as a very real aspect of the human experience that will touch each of us in some way.

I want to tell Katie’s story, to use my own family’s experiences and those of others like us, to effect change and make people listen. It took me until now, as a married mother in my 30s, to really embrace this as my professional destiny, but I think I can finally say that my old ambivalence is gone. Let’s do this.

Please follow Liz on her fascinating blog Disability Fieldnotes or on Twitter @LizLewisAnthro.