As a child, Brendan had many surgeries. Now he helps other kids cope with hospital life

By Louise Kinross

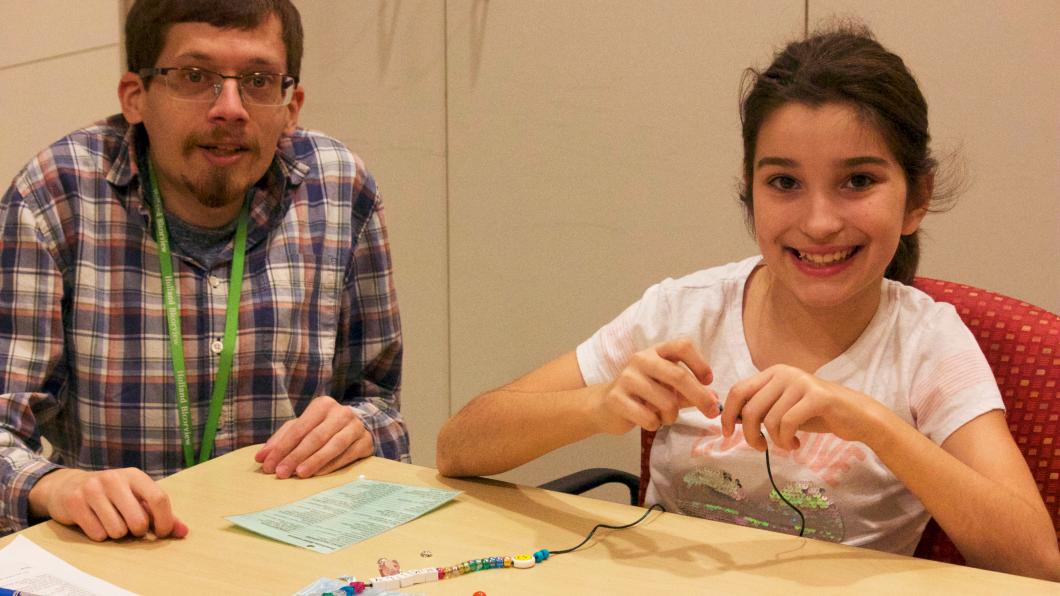

Brendan Prince is a child-life specialist who works with children who are doing inpatient rehab at Holland Bloorview following painful bone surgeries or spinal-cord injuries. He teaches youth practical strategies to cope with anxiety-provoking procedures. Brendan understands firsthand how tough it is for a child to live in hospital for long stretches. He has scoliosis, and had a major spinal fusion surgery at age four. Every year and a half afterwards, till he was 17, he had surgery as he grew. We spoke about his work here and how his personal experience informs it.

BLOOM: How did you get into this field?

Brendan Prince: I became aware of it through my own experience being hospitalized as a child at McMaster Children’s Hospital. All throughout my childhood, from the age of four, I had surgeries.

It’s frightening when you’re that young. My parents and the doctors were forthcoming in explaining things to me, but it was hard to wrap your head around. You notice ‘Why am I different from the other kids? Why don’t they experience this?’ I had a really good family support system with my mom and dad, brother and grandparents.

BLOOM: What was the greatest challenge for you growing up?

Brendan Prince: I have neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), which causes benign internal tumours. They didn’t cause me any challenges growing up. Scoliosis is secondary to NF1, and I had to wear a body brace from my hips to my neck from age four to 17. That was the biggest challenge. It was uncomfortable and hot, and limited my mobility. We called it my armour.

No one ever teased me about it. Everyone was very accepting through public and middle school and high school. One or two kids might say something, but then other people would stick up for me.

BLOOM: How did you get interested in child life?

Brendan Prince: I felt I could really connect to kids who were experiencing health challenges, given what I experienced as a child. I’ve always liked being around younger kids, and I had younger cousins who I saw grow up. I thought adding the component of someone who had experience being hospitalized would be beneficial to children.

BLOOM: Did you develop strategies as a child that helped you cope?

Brendan Prince: My parents were my main support. As you see with clients here, mom and dad don’t leave the bedside, or they switch off with each other. I always had the comfort of a close and trusted person with me.

My dad was good at distracting me by being goofy when I had procedures. I received good medication for pain, and I kept busy in the playroom playing video games. Like a lot of kids, I’d get upset when it came time for a surgery. I’d have typical worries like what happens if I die in the surgery, or I’d think about being asleep and not knowing what’s going on, or I’d worry about pain.

BLOOM: You mentioned you see a number of children each day for about an hour. What kind of things do you do with them?

Brendan Prince: If I’m working with a kid who is having pain, I might teach them about what chronic pain is, coping techniques such as deep breathing, distraction and guided imagery, and therapeutic activities to express their emotions.

BLOOM: What makes for good distraction?

Brendan Prince: For the teens, iPads and iPhones and technology are the go-to. For younger kids, it can be blowing bubbles, or having our therapeutic clowns come in, or doing deep breaths to calm your body down physiologically. We might imagine we’re on a beach, and picture and feel everything there: the colour of the water, the grains of the sand, how hot the sand feels on your feet, how cold your Coca Cola is, and the sounds of the birds. That helps get you into a different mindset.

BLOOM: I know you also use dolls to help children.

Brendan Prince: Yes, we do medical play with a cloth doll. We have the kids draw on a doll to personalize it. Sometimes when they do, they draw a sad face. When we ask: ‘Why does the doll have a sad face?’ the child will say ‘He or she is having a dressing change, or a surgery, or a PICC line.' The doll is really a reflection of them and what they’re experiencing.

Depending on the child, we might put an IV in a doll and they’ll push the coloured water through to show this is their medicine. I sewed a demonstration port into one doll, so a kid could practise putting the port needle in. Then we would practise their coping skills. ‘When we’re having a port access, we can look at our iPad. What should we watch?’ We set the plan for what will happen, and they practise it over and over. We can clear up misconceptions, and lessen their fears and worries.

BLOOM: What is the greatest challenge of this work?

Brendan Prince: Resources. Child life could be used in so many different areas within hospitals, but budgets limit us.

BLOOM: It could be used in a lot of outpatient areas.

Brendan Prince: When I worked at IWK Health Centre in Halifax, I covered five different services, including cardiology, general surgery, ear, nose and throat, oral surgery and burns and plastics, and the clinics associated with them.

I like working with clients of all ages, but teens can be a challenge. They have different interests. We think we have an idea of what’s cool, but now I feel like I’m old. You know that saying ‘too cool for school?’ Trying to make a connection with them, and getting to know them, can take longer.

BLOOM: What’s one of the joys of the job?

Brendan Prince: Knowing that you made a difference, as you see a kid progress. Say they had trouble swallowing pills, and I’ve done teaching with them, and they can overcome that worry and gain a new skill. You see how proud they are. Then later they may be able to transfer their coping skills to different situations. Perhaps a parent will say to them: ‘Do you remember that deep breathing we learned?’

BLOOM: How does your personal experience influence your work?

Brendan Prince: I don’t ever disclose what I’ve been through, because I need to be aware that my experience may not be their experience. Every child is unique, and the way they deal with things is unique, and we have to adapt. I do think that when children see I have a physical disability, it can help break barriers. They might feel they can relate to me because they know what it’s like to have a health condition.

BLOOM: Have your ideas about disability changed at all?

Brendan Prince: The main thing that’s changed is recognizing how inaccessible the world around us is. I never really noticed that before. Given there are kids here who use walkers or wheelchairs or depend on oxygen, now I see barriers everywhere. Like getting on the TTC—I take that for granted. But then I look at a subway map, and see only half of the stations are accessible. Or an old streetcar pulls up with steps. It’s really opened my eyes to issues of accessibility and inequality.

One thing I really like about Holland Bloorview is that they do hire people that have disabilities. It’s nice to see that they value the skills we have. Other hospitals are more talk than action. I’m still learning about the culture here. So far it’s been very welcoming and inclusive, and people are there to help teach you.

I see some of the kids that have really high needs, and their families, and it blows me away how the parents and kids just deal with it. I feel like I would be totally lost, and look how resilient they are.

BLOOM: Is there anything you do to manage stress?

Brendan Prince: I like going home and relaxing. I have my family not too far away, so I can call to talk to them to work through any situations. That support is nice. I like cooking and baking. That’s my stress relief.