'Cancer throws you in the deep end'

By Louise Kinross

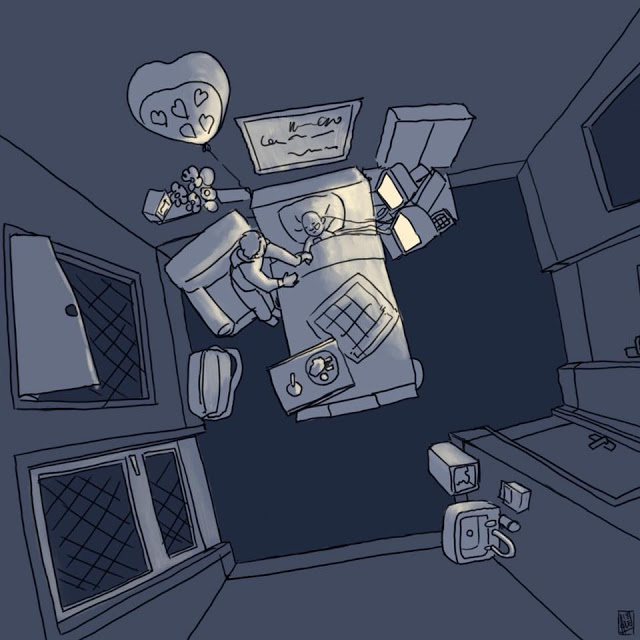

The other day I saw the image above on social media and clicked on I draw childhood cancer, a Facebook page run by Angus Olsen. Angus, who lives in Australia, is trained in animation and began drawing his experiences when his daughter Jane was diagnosed with an aggressive cancer in 2016 at age 2. “It was a way to visualize the unspeakable,” he says. Since then, parents of children with cancer worldwide have written to say his illustrations make them feel less alone. He’s now making comics to help explain procedures, like inserting a nasogastric (NG) tube, to preschoolers. These will help parents, child-life specialists and other professionals reduce anxiety in hospitalized children. We spoke about the role of drawing at his daughter's bedside, where he lived for months.

BLOOM: When did you first start drawing about Jane’s experience as a cancer patient?

Angus Olsen: I was living with her in hospital in 2016 when she was doing some heavy chemotherapy, and her tumour grew rapidly—it did the opposite to what you expect them to do. It became quite serious. I was extremely lonely, and people kept asking me questions I didn’t know how to answer. So I started to draw a comic called Jane to explain how lonely it was, and to explain situations that you can’t quite explain in words. My wife had been living with Jane until she came down with flu, and then we swapped.

BLOOM: Did you draw on a daily basis?

Angus Olsen: I kind of drew when I felt like it. I did a lot of sitting, staring at Jane’s numbers, and hoping they’d go up. It wasn’t just in her hospital room, but in the oncology clinic where she received chemo. One day, for some reason, she wanted to fly, so I drew her as a pilot flying a plane (see below).

Originally I was drawing for myself, but then I put them on Facebook. It was to try to explain to people ‘This is what it’s like.’ Then I joined a couple of pages dedicated to dads of children with cancer and started to make friends. Some of the dads had daughters who were at the same stage of treatment. Even though cancer is very individual, and everyone is different, they were very helpful because I could ask ‘Is this normal?’ Cancer throws you in the deep end.

While your child is doing treatment you feel like you’re abusing your child. You know it’s for their sake, and you just hope on the other side that they come out close to normal.

As I became friends with other cancer dads, there were little things that impressed me about their kids. The first child I drew like a warrior on a horse, because she was remarkable in how she continued to have a life despite what was going on. It started off with me asking these dads if they’d like me to have a crack at drawing their child. Rather than send me photos, they would have me go through their Facebook page so that I could see what the child looked like disease-free. Especially for some of the children who had passed away, I wanted to show what the child looks like free of cancer. Because in reality, the children who die are finally free of it.

BLOOM: Parents often feel helpless in hospital when their kids are going through these treatments. Did drawing provide a useful distraction or a way of thinking differently about what was happening?

Angus Olsen: It was a way to visualize the unspeakable. It helped me, but I guess I don’t know how to explain it. I know now that I wouldn’t remember anything that happened after the trauma if I hadn’t drawn it. It felt like it needed to be done—to explain the unspeakable to people and myself.

My most recent art is about placing an NG tube. For a long time when I was in hospital, there was nothing about NG tubes. I didn’t know why I was ramming this tube down my child. I thought maybe there were ways I could be practically helpful to other dads of kids with cancer, by giving them something visual that explains why something like an NG tube is important. I only posted that the other day, and the reaction to it is shocking to me. It’s had more than 70,000 views.

BLOOM: Parents are often asked to hold their kids down for these procedures, and it’s incredibly traumatizing.

Angus Olsen: It feels abusive. You feel like you’re abusing your child. Yet you know it has to be you, it can’t be a stranger doing it. At least that’s how I felt. That was really rough on me.

There were lots of other things, too. Like the bandage on the dressing on the child’s NG tube can tear their cheeks off. The actual insertion is quite quick, but the dressing change can take a long time and cause a lot of pain. When Jane’s was finally taken it out, she’d had it for more than a year. Some children vomit them up, and are irritated by it the entire time.

BLOOM: When you talk about the child’s cheek getting ripped—wouldn’t they have come up with some kind of adhesive to prevent that by now?

Angus Olsen: There’s a lot of technique involved, but sooner or later, the child’s cheek gets worn down, and they run out of skin. And because children are children, and play, sometimes they bump or rub into something, and it tears off. The nurse doing it is very nervous, too. It’s very traumatic on nurses.

BLOOM: That’s what we found in our narrative group for inpatient nurses—that clinicians can have feelings of helplessness and grief when they aren't able to prevent suffering, in the same way that parents do.

Angus Olsen: If the nurse is a new nurse, if they’re fresh at this, you’re a parent comforting a nurse. It’s an intensely personal relationship. Even though it’s the nurse’s job, it’s incredibly traumatic on them.

I had one male nurse at the local hospital say that Jane’s case was the most traumatic thing he’d seen in his life, and it was the only time he’d ever cried in clinic. They’re all clearly impacted by what they do, but they keep going. I have nothing but praise for nurses.

BLOOM: Did you ever make mental notes of interactions with staff you found extremely helpful, or not helpful, in order to later illustrate them?

Angus Olsen: I’m pretty forgiving when it comes to the clinicians. I know they’re human. It’s really a struggle for me to watch a new nurse trying to grapple with what they’ve got to do. You don’t want your child to be the experiment to learn what they’re doing, but you know they’re going to help thousands of children. I’ve never come across a bad interaction with a clinician.

BLOOM: Have you thought of doing a graphic novel?

Angus Olsen: I’ve done graphic novels in the past. Facebook is kind of like a sound bite. People can see an image, interact with it and move on. You can pack a lot into an image, and have it received by many people. The distribution of a graphic novel I don’t think is as wide.

For example, the comic about the NG tube is only eight frames, so you can swipe through it with your child sitting on the bed. I’m looking for a short impression, something that hits someone in the heart and they say ‘Yes, yes, this is me.’

In the future I’d like to draw all of the different childhood cancers.

BLOOM: Did your images have an impact on Jane, or was she too young at the time? Your series about the NG tube could be used by child life specialists to prepare kids.

Angus Olsen: Jane was too young. She was just excited: ‘Oh, that’s me. Daddy drew me doing this.’

BLOOM: Were there any downsides to your drawing? I’m thinking of an interview I did with a dad of a toddler with type 1 diabetes. He was a filmmaker, and when his daughter was diagnosed, he began filming. But at a certain point, he realized he was hiding behind the camera, because he was so afraid of making a mistake with his daughter’s treatment.

Angus Olsen: For me, the downside of this drawing is that these children do die. It’s actually quite a lot of emotion. I’ve had to wipe tears off my iPad at times. It impacts me in ways I didn’t realize it would. Parents of deceased children from all over the world message me to see if I’ll do their child’s portrait. I’ve had to stop doing that, and focus on the work with a broader impact on cancer, so it’s useful to thousands of people. It’s all about using your gifts in the most useful way.

BLOOM: How is Jane?

Angus Olsen: She’s been in remission since 2017. She’s five, and starting school. She’s doing very well, but she’s still having a lot of physio because her cancer made a mess of her legs. So she’s learning how to walk properly and we’re training her to develop her legs. The scenario they gave us was that she’d either pass away, or be on a bag for the rest of her life. The fact that we came out with a relatively healthy child when we were dealing with the reality, in hospital, that she could die, was very, very fortunate.

BLOOM: It must be surreal to have had such an extreme experience.

Angus Olsen: It is. You know that comic of me sitting staring at a blank wall? Cancer parents understand that image. Very recently, Michael Bublé’s been talking about his struggle with what’s been happening to his son. And he says things like ‘I can’t talk about it. I can’t explain it. I don’t have words for it.’ I understand that. We cancer dads understand this poor guy is riding our world. Even though his child is in remission, you don’t go back.

BLOOM: You mentioned that the other parents living in hospital were primarily moms. Was that isolating?

Angus Olsen: My wife made a lot of friends because it’s usually mothers living there. Yes, I’m a very private person, and I don’t do well with counselling and things like that. I found the Facebook groups for dads far more helpful than talking to a parent in person.

Our daughter’s social worker was invaluable to me, and certain nurses were very comforting. Her surgeon was very good to me as well. So I did have people. But with the urgency of what was happening, and the reality that she could die today, it was too much. I couldn’t leave her bedside to sit down with another parent.