'Autism isn't a thing. It's how we go about things'

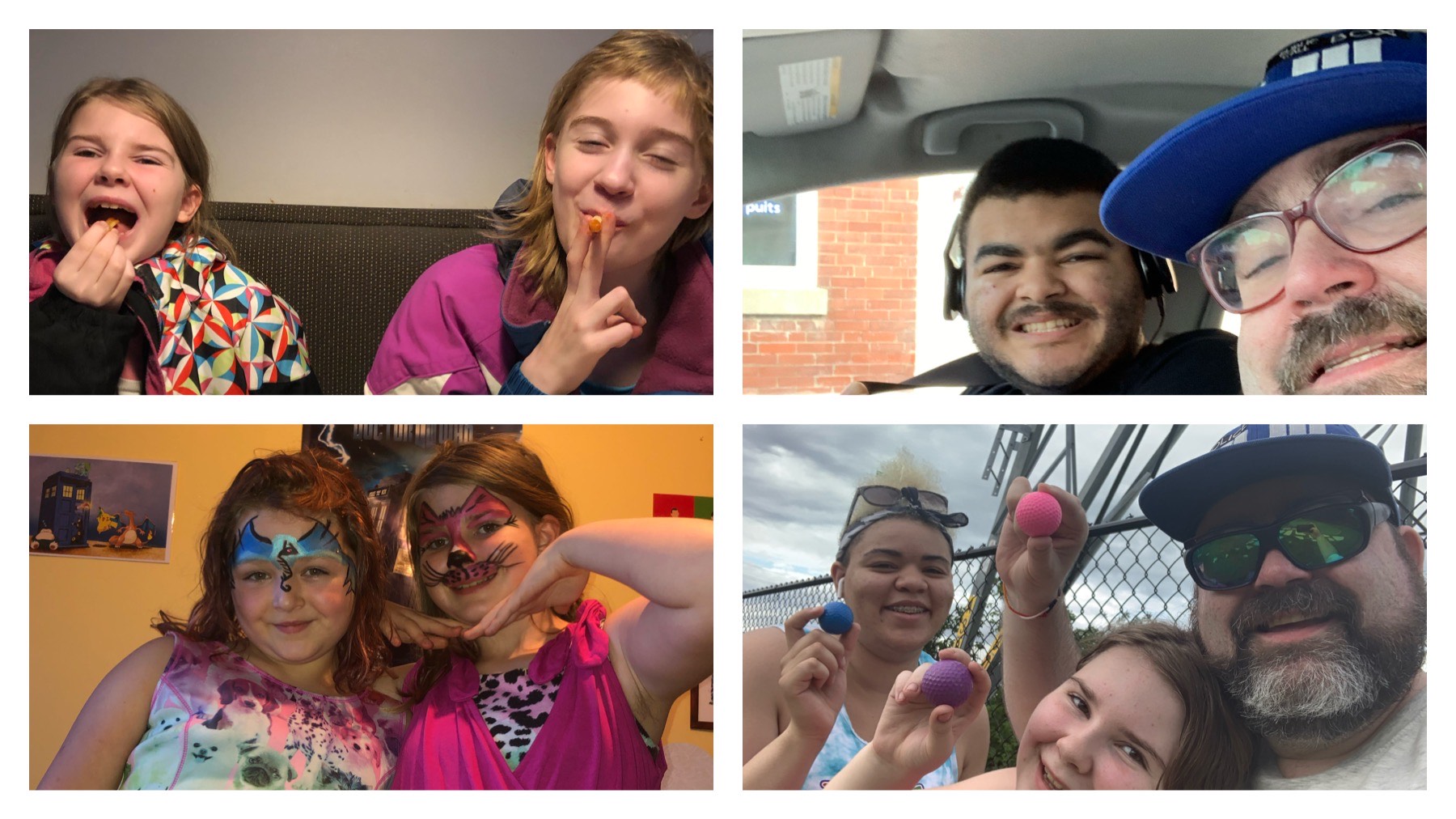

Photo of Matthew Dever with son Ashley

By Louise Kinross

Autistic activist Matthew Dever gave a fascinating workshop in August with Holland Bloorview’s Dr. Melanie Penner about the words we use to talk about autism.

The ECHO Ontario Autism session looked at why clinicians need to move from the language of awareness to acceptance.

“Moving towards autism acceptance allows you to see autism as an acceptable part of the way humans are,” Matthew said. “It’s not as common, but it’s not something to be scared of, not something to be feared. It doesn’t take away the fact that there are challenges,” but it focuses on strengths.

For example, instead of talking about “symptoms,” use the word “traits or characteristics,” which is neutral, Matthew said. “There’s something there, but it’s not wrong.”

Instead of referring to “challenging” behaviour, use “interfering” behaviour. “Behaviours are a form of communication,” Matthew said. “What you see may be challenging to you, but it’s not necessarily challenging to the child. We want to shift the focus to what’s affecting them vs. what’s affecting people around them. When it’s a ‘challenging’ behavior, it’s something that needs to be ‘fixed.’ When it’s ‘interfering,’ you want to help the child around it.”

Matthew was diagnosed with autism at age 33, after their* son received the diagnosis at age three. Three of their five children are autistic. We spoke about Matthew's experience with a late diagnosis and raising children. *Matthew's chosen pronouns are they/them.

BLOOM: What was it like growing up without an autism diagnosis?

Matthew Dever: I was an awkward child with so many issues. I was diagnosed with so many things—ADHD, Tourette’s. I was in gifted classes but I was socially inept. I didn’t connect with people well and I was bullied a lot. I was a social misfit. So many things were confusing for me as a kid, and if I’d known I was autistic, it would have helped a lot. That’s why I do a lot of advocacy. I don’t want to see kids and adults struggle through the things I did.

BLOOM: How did you come to your own acceptance of autism?

Matthew Dever: The day I was diagnosed was a good day. I could understand it more. I started blogging about it and writing about it and doing advocacy with different levels of government. I latched on to a community of autistic adults who felt strongly that the whole concept of autism awareness was creating a problem, because it was making people aware only of the challenges, of what we can’t do.

Awareness breeds fear, but acceptance changes attitudes. Acceptance means finding ways to accommodate. It means knowing that the autistic brain isn’t wrong compared to a neurotypical brain, it’s just different. Humanity is full of diversity and all of it is okay if we can accept and move forward with what we need to do.

BLOOM: What are some ways you’ve changed the way you talk about autism?

Matthew Dever: One of the biggest things I hope to eradicate is the concept of functioning: ‘my kid is low functioning’ or ‘my kid is high functioning.’ Instead, we need to talk about kids’ needs. All of us function at high and low levels in different domains depending on circumstances and our age. We’re all autistic, and there’s no competition as to who’s more autistic. If we remove the functioning label and talk about the strengths and challenges, we’re going to help that child’s needs.

The biggest issue isn’t with behaviour—it’s with those behaviours that get in the way of a child’s ability to be productive and thrive, or that seriously impact those in the environment around them. Not all behaviours need to be addressed.

The autistic ways of doing things are normal for autistics.

The way we perceive things is normal. The sensory overload is normal for autistic people. The way autistics don’t have as much of a problem communicating with each other as with neurotypical folks shows that we don’t have a deficit in communication, we have a different way.

We need to understand and accommodate and meet needs, and stay away from fixing.

‘Intervention’ means to fix. I much prefer the words ‘support, guide, provide service to.’ Each of those words means something similar, but the inflexion behind it is positive or neutral.

Parents have a natural tendency to think autism is the thing they’re fighting. Autism isn’t a thing—it’s how we go about things. It’s something inherent. Children can be strengthened by aspects of it, and challenged by aspects of it. Autism is thoroughly and 100 per cent a part of the child. It’s the environment of society and the barriers there that they’re fighting.

If parents can get that attitude toward their child, they’ll be able to support their child, instead of harshly being at war with that part of their child that they see as the enemy. I see parents post things like ‘We lost our battle with autism today, and we’ll start again tomorrow.’ As kids get older, they internalize that.

BLOOM: You told an interesting story about how you went to your first parent support group after your son was diagnosed, and it wasn’t what you expected.

Matthew Dever: It was one of the most difficult experiences in my life, because it was so negative. It was all about the challenges. No matter how challenged your child is, they’re going to grow. Part of the problem is that parent support groups are run by parents with young kids, and they often don’t have older parents who have more experience with older kids. We need to ensure that support groups have a mix of younger and older parents, as well as autistic adults helping as well. We need to show the reality that hope exists.

BLOOM: What has been the biggest challenge of raising your autistic kids?

Matthew Dever: School is the biggest challenge. School is all about compliance, it’s not about accommodating and teaching. There are always more excuses about why they can’t support a kid than why they can. In New Brunswick, about eight years ago, they adopted an inclusion-first approach. They start with inclusion, and exclusion is the rare exception and has to be really justified. Teachers and educators are encouraged to figure things out. In Ontario, you hear ‘Well, we’ll try to do this.’ In New Brunswick it’s ‘We’re going to do this, we’ll figure it out.’

So many parents day to day here are waiting for the call that says ‘Come pick up your kid, it’s not working well today.’ But it’s not documented, and there’s no plan as to what will change.

It’s not that the province isn’t giving enough money to fund exceptional education. We’re not prioritizing what they’re doing with it. It’s not clear what supports are available, and it’s always a fight to get any of them. Some days I feel school harms more than helps, and it’s so demoralizing.

BLOOM: What’s the greatest joy of raising your kids?

Matthew Dever: They just do things so differently. When they get an opportunity to follow their ideas and strengths, and follow their interests, it’s seeing them do amazingly creative things. My son does mash-ups of songs on YouTube. As a kid I was told he wouldn’t be able to finish high school and would be looked after by the government for the rest of his life. He’s not necessarily independent outside of the house, but he has a bigger following on TikTok than I do.

I took my 14-year-old daughter out of school for a year because she was having so much difficulty there. She’s very smart, but expressing her thoughts was difficult for her. Now she’s found a community online and some of the artwork she’s doing blows my mind. They do drawings of characters or photo edits of comic and movie characters. It’s a lot easier for her to make friends online than it is in person.

My 12-year-old is just so funny and creative, and cares deeply for people. Last year she got so involved with climate change and wanting to know more about it. She had a huge growth jump. She went from being a little girl to being a big girl over night. She ‘tweened’ out on me.

I love seeing my kids grow and thrive and I talk to them about autistic pride and being okay with being who you are.

BLOOM: What advice would you give to parents earlier on in the journey?

Matthew Dever: The biggest thing is that your child at two won’t be your child at 20. They will grow and change. You need to focus on how to accommodate them to build up their strengths so that they’re even stronger, and so they know they’ve got a lot of good qualities that will help them adapt. Accommodate, strengthen, adapt. That’s how you help kids thrive.

BLOOM: What would you tell health professionals?

Matthew Dever: It’s a similar message. Focus on the kids’ needs and not on their behaviours. Find their interests and strengths and use those to help them through the challenges.

BLOOM: Two of your autistic children are girls and you said they were diagnosed at around age six, while your son was diagnosed at three.

Matthew Dever: There hasn’t been a lot of research until recently about how autism presents in girls. Boys who can’t fit in tend to act out. Girls who can’t fit in tend to go inside themselves. That seems to be the difference, and why they get missed.

We need to stop the idea that autism is a behavioural condition, so we can open our eyes to see more of the kids that need supports at a younger age. If any kid is struggling socially or with language or sensory issues, we need to rule out autism first.

Ask Autistics Ontario is a Facebook group where parents and professionals can ask adults with autism for advice. Visit Matthew's website to read their* writing about autism and find resources. Below are more photos of Matthew and family. *Matthew's chosen pronouns are they/them.