When a child has 24-7 needs, mothers bear the costs

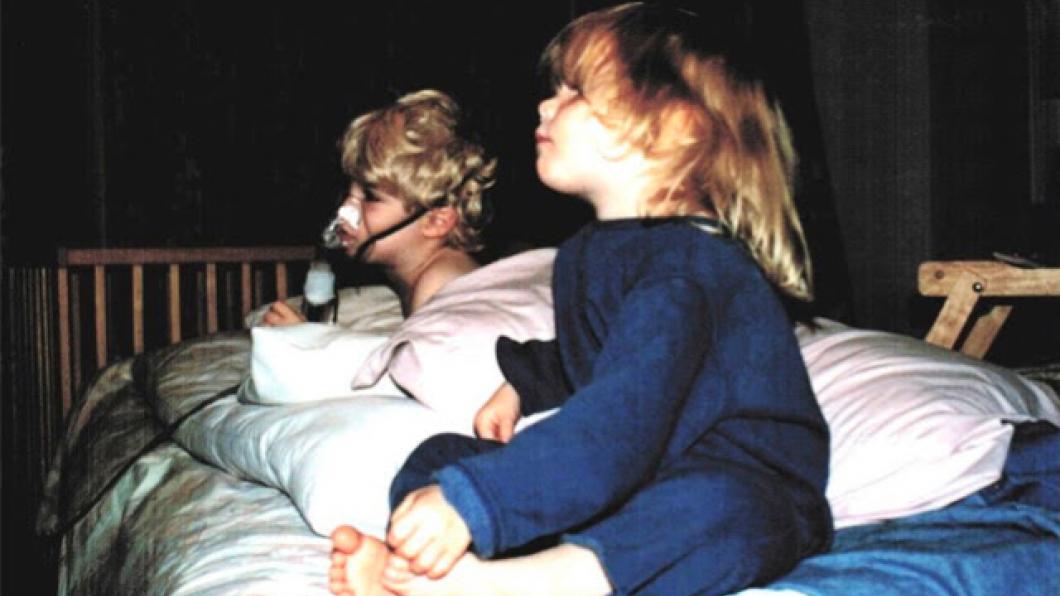

An early photo of two of Sheila Jennings' children

By Louise Kinross

As the mom of a son who had severe asthma and a life-threatening immune condition, Sheila Jennings learned firsthand that it was impossible to work outside the home and tend to her child with complex health needs.

“My interest in the support rights of mothers of severely disabled children began after I got divorced and set up my law practice while caring for three children,” she says. “My son missed about 40 days of school in Grade 7, and a similar amount in Grade 8. He had severe infections, was followed by four clinics, and was frequently in the Emergency Room. One time I was just about to go into the courtroom, and I had a call that something was wrong at school. I called my son’s father, who is an emergency room physician, to ask if he could find out what was going on, and he said: ‘I have someone here with a screwdriver in their head.’ Even when I had a spouse, he didn’t necessarily have the ability to drop everything. I started to get sick myself in 2005, and when I became very ill, I had no choice but to close my practice.’”

Sheila recently defended her PhD thesis called The Right To Support: Severely Disabled Children And Their Mothers at Osgoode Hall Law School. “Within complex care, visible and hidden costs have been offloaded onto caregiving mothers by governments,” she writes in the study's abstract. We spoke about her research, and why she believes that the extraordinary demands currently placed on Canadian mothers of children with complex needs might constitute ‘cruel and unusual treatment or punishment’ under section 12 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

BLOOM: What was the purpose of your research?

Sheila Jennings: I wanted an answer to the question: ‘What are the legal rights to support for mothers who have severely disabled children, and what should they be?’ I thought it would be a very simple question. But it was anything but.

My project looked at literature, as well as 184 cases, which were mostly Canadian. These were cases where caregiving mothers brought law suits or defended against the actions of others. They took on the Canada Revenue Agency or social benefits, or said they needed more spousal support due to their child’s complex needs. I used cases from every jurisdiction and from an online database, so mothers can easily access them in support of their own complaints.

BLOOM: What did you find?

Sheila Jennings: It was fairly uniform that if the moms were single and unable to work, they were falling into poverty and struggling, and they were often opposed in cases they brought. There were sympathetic judges, but caregiving mothers’ support needs slid between categories in law, and often couldn’t be helped in court. There was the occasional win, which might take months or years. Litigating mothers became embattled while also providing care. Lawsuits are exhausting and stressful. And each case was usually just one win—there were hardly any systemic wins, where the court said from now on every mother who needs this support will get this amount.

One of the problems is that child support is considered for the average child. You can ask for add-ons, but the cost of respite care and basic nursing care must typically be fought for.

BLOOM: Can you describe one of the cases?

Sheila Jennings: One public law case was brought by a woman who was divorced and had a six-figure income. She had three children. She came to the Social Benefits Tribunal in Ontario to ask for funding through Assistance for Children with Severe Disabilities (ACSD). ACSD had said no, your income is over the funding cap of $60,000, so you can’t have the amount you say you need. Yet 50 per cent of her income was going to disability-related supports.

She’s a good example of someone who had a full-time job and a big income, but it still wasn’t enough to make it manageable. The tribunal agreed that she'd made the case for the additional money, but it was on a one-off basis. Three years later, she was back in front of the tribunal when her funding application, over what was, in fact, a discretionary cap, was again refused.

I have so much admiration for these women. They’re living extraordinarily difficult situations with their children, and they’re rolling up their sleeves and taking on the government, or the other parent who doesn’t want to pay. The other parent says it’s the government’s job to pay, and the government says it’s the other parent’s job.

The system for disability supports across Canada is very fractured. It’s not a uniform system, nor can it be easily accessed. The ministries frequently shift people around and change programming. There's rarely an expert in charge with a great deal of knowledge on the file. It’s very hard to get systemic change or sustained change. Much of the work caregiving mothers do is invisible. People can be sympathetic, but they don’t realize how much work is involved and what the implications are. This is a different form of motherhood, and it needs to be supported as such.

BLOOM: I remember when my second child was born without disabilities, being absolutely shocked at how easy her care was.

Sheila Jennings: Yes. Reflecting back on when my third child, who is athletic and healthy, was born, it highlighted for me that the mothers I was studying were different. The support needed for a child who is playing soccer, has tons of friends, doesn’t get sick often and has no physical issues that land them in hospital, is not comparable.

I think professionals who are going to be working with caregiving mothers should be going into the home for two to three days, to see what’s involved. In my project I decided not to call the mothers 'complex-care moms.' I decided to use a feminist lens and use the term 'maternally complex care.' It’s a different form of motherhood.

Too often, people see a regular mom, and they see the complexity as medical- and hospital- and doctor-centred. That is treatment.

It's the mother who is providing the complex care.

Maternal complexity, rather than medical complexity, gives status recognition to the woman who's doing the care, and Canadian research shows it’s 97 per cent women. Many have given up jobs to care for a child with additional needs. It's an important role in society that carries a price, and it doesn't come with workers' compensation, pay or a pension.

I'm interested in how these women are seen and treated in our culture. They get sympathy and sometimes pity. Or even admiration. But care of this kind is not recognized as the work it is. I’ve said before, going to court as a lawyer on a difficult file was easier, any day, than dealing with the objective and subjective maternal complex-care issues that would arise with my son.

Caregiving mothers may be traumatized while providing care, and at the same time you’re also running the house and doing everything else women are socially assigned to do.

My research also showed that it's hard for children with complex-care needs to see their mother's exhaustion from the heavy lifting, so to speak. It's an issue for children too.

BLOOM: Did you come up with any recommendations for change?

Sheila Jennings: One recommendation I considered is the treatment of caregiving mothers in light of section 12 of the Charter, which provides that ‘Everyone has the right not to be subjected to cruel and unusual treatment or punishment.’

I made preliminary arguments that to have mothers alone held responsible for this care, in the manner it’s currently provided, meets a legal test to show section 12 is violated.

Mothers’ health is being negatively affected, and not just a little bit. There’s even a study out of Australia about how mothers of complex children have much higher levels of mortality.

BLOOM: There was also a population-based study done by Dr. Eyal Cohen at SickKids that showed an increased risk of early death in mothers of children born with anomalies like heart disease or Down syndrome.

Sheila Jennings: Right. So we know this correlation is an issue.

BLOOM: What was the typical outcome of the legal cases you analyzed?

Sheila Jennings: Overall, you can see that the mothers are embattled. For example, there was a 2004 mother with a child with progeria, which causes early and rapid onset of aging. She wanted an increase in night nursing hours, and she wanted the government to subsidize, or pay for, private nurses she had to hire when the CCAC nurses didn’t show up. She also didn’t want CCAC to send her personal support workers who didn’t understand her child’s condition.

BLOOM: I looked at the case you sent, and she also wanted registered practical nurses who did overnight shifts to be paid at the registered nurse rate to better retain them. And she wanted a back-up plan with the hospital, so that CCAC-booked shifts wouldn’t be cancelled.

Sheila Jennings: Yes. Unfortunately, she had no legal leg to stand on. The CCAC client was her child, not her. I address this issue as one of relational rights in my project. She lost her claim. It’s 15 years later, and these home-care failures haven’t gone away. We read about the same problems from parents like Marcy White and Samadhi Mora-Severino. We have another generation dealing with the exact same thing.

BLOOM: How could section 12 be used to create change?

Sheila Jennings: Lawyers and mothers doing this kind of care need to get together to list the harms they’ve experienced, and to consider what kind of legal action is possible.

For example, it’s not okay to be on call 24 hours a day, nor to have consistently interrupted sleep for years. This is way outside the gamut of modern day labour standards. A mother interviewed recently by a Montreal newspaper said ‘What kind of world do we live in, where I’m supposed to be up, day and night, providing heavy physical care?’ There isn't a union or workers' compensation to protect these women when they're injured or become ill. Caregiving mothers bear the risks. That's monstrous, and as a society we can do better.

BLOOM: You mentioned that you looked at how our culture views mothers of children with disabilities.

Sheila Jennings: Yes, I did, and it's very interesting. The special-needs mother is romanticized, and put on a pedestal, and is portrayed as having a high cultural value. You think of Princess Diana in Pakistan holding a dying child, or Princess Kate landing on the runway in Alberta, and hugging a child who had obviously been in cancer treatment.

But that runs contrary to the way that caregiving mothers, particularly those who provide maternally complex care, are treated at a provincial level. The reality is that they’re often isolated and alone. Donna Thomson’s book The Four Walls of My Freedom alluded to that. There is exclusion, not only of severely disabled children, but of their mothers too.

BLOOM: What are your next steps?

Sheila Jennings: I hope to teach again this year. I taught last year at the University of Ontario Institute of Technology, and I was able to bring these issues up in my family law course and also, to a degree, in my human rights course. Students were very interested. I'm also in the midst of writing two papers and preparing a proposal for a book with an academic press.

In addition to her years practising family and child welfare law, and doing her PhD, Sheila Jennings did an MA in critical disability studies. You can follow her on Twitter @SheilaKJennings.