Seeing blindness in a new way

By Louise Kinross

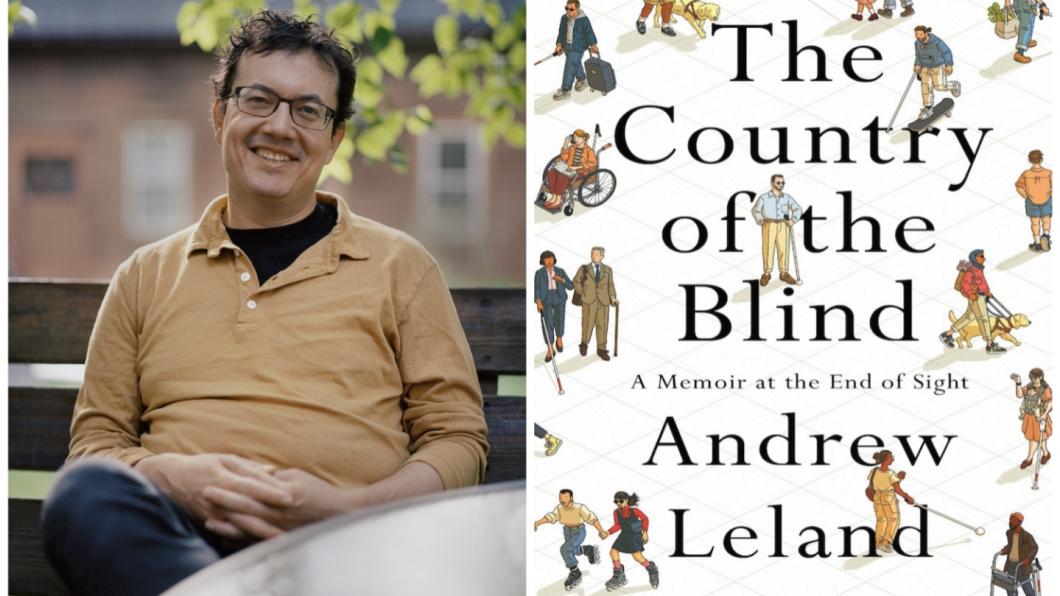

The Country of the Blind is a fascinating book about journalist Andrew Leland's gradual loss of sight over decades due to a genetic eye disease. It was named one of The New Yorker's best books of 2023. In it Andrew shares how his experience of blindness generated new insights and growth as a person, while at the same time threatening his sense of identity. He looks at blindness as a culture, from a historical perspective, and in relation to medicine and technology. We spoke about his book.

BLOOM: The first thing I wrote down when making notes in your book was: "Blindness is not what you think it is." Was that a reader goal in writing your book?

Andrew Leland: Yes, definitely. Anytime I'm thinking about a reader, I'm mostly thinking about my own experience to an idea, and I had the experience of having a lot of misconceptions about blindness. Then when I researched the subject I realized it wasn't just my own personal misconceptions, but that there's a broad societal misunderstanding. So certainly my hope is that the reader will follow me on that path towards reconceiving it.

BLOOM: You are slowly losing your sight, but most people think of it as all or nothing. You write about the pain of your in between state. Can you speak a bit about that?

Andrew Leland: I'm still in that in between state and it may be here for a long time. One of the misconceptions that you are alluding to is that blindness is a binary, and that creates some of that pain of the in between, because one feels like one should be fully blind or fully sighted. Few people understand the ambiguity that being in between brings with it. I think that's the primary pain. The other part that's difficult is the sort of anticipation of what life will be like and how you will do X, Y or Z without vision or with less vision.

BLOOM: Early on you write about being ambivalent about using your cane. Near the end of the book you note that the cane can't be hidden, and that's good, because blindness isn't something to be hidden. How did you develop comfort in using your cane and identifying as blind?

Andrew Leland: That's a good question. The passage you are alluding to is me kind of paraphrasing the National Federation of the Blind. I was sort of parroting their philosophy. When I went to their training centre I carried a folding cane and the version they make students use is a straight cane.

BLOOM: So you can't minimize it.

Andrew Leland: Yeah, it's a big, long stick. It's stronger and lighter than a folding cane, but the main thing is don't be ashamed of it. Who cares if you have to slide it under your seat on the bus or under the table at a restaurant. When you first start using it it's embarrassing, but then it becomes natural.

How I developed comfort was a matter of practice. Part of it was cane training and getting more comfortable with the techniques I learned, but the bigger part was breaking the seal on it over and over again. The same way you might with writing or exercise or meditation. The first time you do these things it feels exotic and difficult and foreign and hard. And not that it ever gets super easy, but if you make it a daily part of your life it becomes part of your life.

BLOOM: What advice would you offer a child or adult who is slowly losing their vision and is earlier on in the process.

Andrew Leland: The tricky thing with retinitis pigmentosa is that it goes at a different rate for everyone. One of the challenges is staying ahead of it. So when I first started using a cane I didn't totally need it and still saw lots of things when I was walking around. Over time it went from me using it five per cent of the time to the cane giving me good information 10 to 20 per cent of the time. Now I'd say 70 per cent of the time the cane is giving me information I need.

There's a wide range of blindness skills that someone who is slowly losing sight needs, whether technology, home management, travel, or literacy. The advice is you don't have to go full on now, but to keep a couple of steps ahead of your vision loss, whatever that means to you.

That way when your vision does change, you're not high and dry: So okay, this is hard, but look at that, I already know how to use a screen reader and now I'm relying on it 50 per cent versus 20 per cent.

By frontloading that work it makes it easier to go through an adaptation period, as opposed to doing all that work during the transition period. You may also be going through emotional stuff and the last thing you want is to have to memorize screen reader hot keys when you're going through emotional upheaval.

So instead of having to start from square one, you're patiently practising in advance.

BLOOM: You talk about your joy in learning to read Braille with your fingers. How did you read your book for the episodes you taped for BBC?

Andrew Leland: Visually, it was magnified to a certain extent. But I'm trying to practise what I preach in terms of staying ahead of changes in my vision. So I have a big monitor and I look at a screen with magnification, but I also use a screen reader. It basically converts all of the items in a graphical user interface into audio. When I first started I was using the screen reader zero per cent of the time but now I'm using it at least 50 per cent. I can grab one or grab the other.

BLOOM: You write about the stigma attached to blindness historically. It reminded me of a mother who told me a story about her son who had a stroke. One of his resulting disabilities was blindness. His initial response to the diagnosis was: 'I can't see. But I'm not blind!' Do you relate to that?

Andrew Leland: I agree with the spirit, but not the letter of that. I think it's important to destigmatize blindness, in part by embracing the word. You see a similar argument being made with the word disability. I cannot stand 'handicapable' and 'differently abled' and special needs." But the spirit of what he's saying I'm 100 per cent down with.

BLOOM: I think he was trying to throw off the stigma. In your book you talk about how strangers will avoid you and cross to the other side of the street. How has blindness impacted old friendships with people who knew you when you had more vision?

Andrew Leland: I wouldn't say I've been treated in a stigmatizing way by any friends, but there's awkwardness, and I don't blame people for being awkward. I was awkward when I first encountered it.

After I say to someone for the third time 'Please ignore my blindness and I'll let you know if I need anything' and they keep grabbing my elbow—those are the friendships that have devolved. But because my vision loss has been gradual, it's been easier for friends to adapt to. If I was totally blind that would be a much more dramatic experience for my friends, and certainly for me, and I'm not there yet.

BLOOM: Your son comes across as being very matter of fact and accepting of your vision loss. Has your disability affected him in positive ways?

Andrew Leland: I really do think so. For five years I've been thinking and talking so much about this, as I've been writing and researching it, and naturally kids internalize the stuff their parents are obsessed with. So it's very much on his radar. I see in him a sophistication and a level of engagement and empathy with disability, and more broadly with the social aspect of it, that is really special for someone his age.

BLOOM: I loved this insight from a blind person you interviewed about travelling while blind. 'You have to be willing to get lost, and be confident in your ability to figure it out.' I thought that was a great way of framing travel while blind as an adventure.

Andrew Leland: During the day, and in a familiar environment, my residual vision is quite handy. But last night I went out for a walk on an unfamiliar route and it was dark and I definitely had that experience. I was still getting visual cues, so I could see up ahead of me a street light. But there were plenty of instances where I didn't know if there was a sidewalk or not and I would swing my cane up and 'Oh, there's not, my cane is hitting a front lawn, so I'm going to have to ride this curb.'

I wandered around for an hour and I was enjoying the walk. It wasn't like I was trying to get home. If I didn't have my cane, and have the training I had, I probably would have busted a knee on something.

As the person I quoted said: 'It's a magnificent puzzle, as long as you're not in a hurry.' You have to be willing to retrace your steps and if you're wrong, you might have to go all the way back. Last night I found a route I know but the road doesn't have sidewalks and it's twisty with cars going fast, so I took a different road, which was the long way.

BLOOM: You write about how medicine positions itself against blindness, and a research charity in the U.S. uses the tagline the Foundation Fighting Blindness. This reminded me of the SickKids Hospital campaign SickKids vs. At one point it included SickKids vs autism. Autism, like blindness, is seen as a culture now, with positive attributes, so being told that an organization is fighting blindness or autism feels like they're fighting a part of you.

Andrew Leland: I totally agree. I'm not against blindness. I still go see the eye doctor and I take the drug she tells me to take, but I'm definitely not signing up for clinical trials.

I think I've heard this among the hard-core blindness activists, but it doesn't feel quite the same as autism. I think the neurodiversity community and the deaf community have a much more fraught relationship with medicine. There is that rhetoric that you're describing an eradication of a population and a culture. Blindness is a tricky one. I think blindness is a culture, but it's less well defined than the neurodiversity movement or the deaf rights movement.

Whenever I think about curing blindness and those sorts of medical arguments, the reality is that there's a lot beyond disease that can blind you. If I'm thinking about where to direct resources and research, yeah, if there are curable forms of blindness, great. We should do it. But for me, expanding access to books and employment and literacy and other resources is where my energies lie. The fact is there will always be blind people.

One big problem I see in medicine is if your job is to mitigate this eye disease and preserve vision, there's a failure point where okay, this doesn't have a treatment, there's nothing we can do for you, and we're kind of done here.

I've heard horror stories about doctors who wash their hands of a patient: 'Sorry to inform you you're blind now,' and it's received as a death sentence, and the doctor offers no path forward. There are ways you can adjust and adapt and live a good life.

You can listen to Andrew read excerpts of The Country of the Blind on BBC. Like this interview? Sign up for our monthly BLOOM e-letter, follow @LouiseKinross on Twitter, or watch our A Family Like Mine video series.