'Health care is desperate for more tenderness'

By Louise Kinross

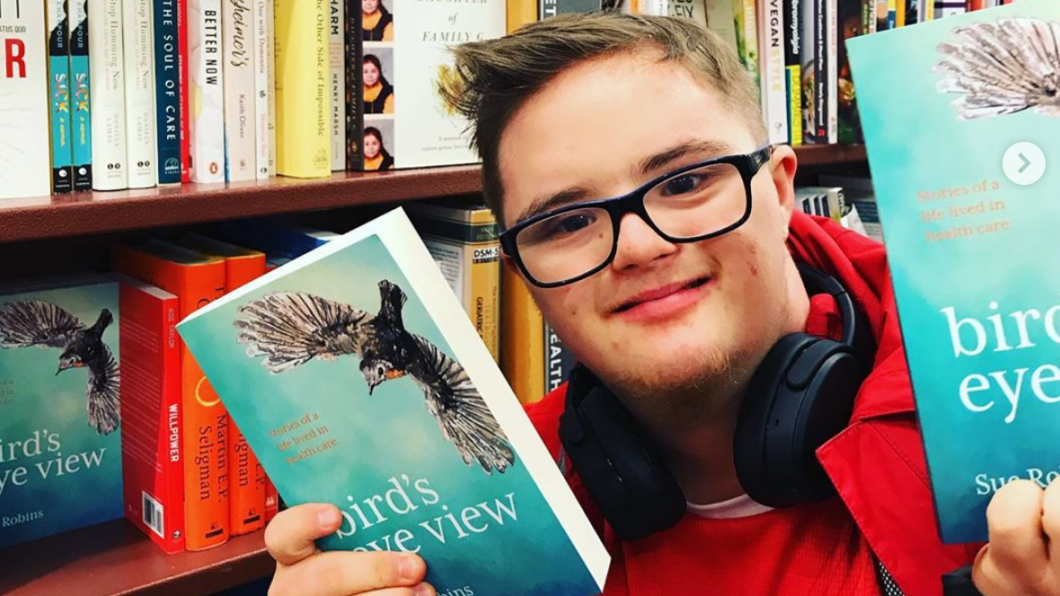

Last week Sue Robins talked about her new book Bird’s Eye View: Stories of a life lived in health care at Holland Bloorview. Sue trained as a nurse, before being told she wasn’t tough enough for the profession, and went on to work in administration in hospitals and in a provincial health ministry. After her son Aaron (photo above) was born with Down syndrome, she became a disability advocate and worked as a family-centred care expert in children’s acute care and rehab hospitals. Many of you will remember her essay The invisible mom, about the social isolation parents of kids with disabilities experience. It had over 43,000 hits on BLOOM. Three years ago, Sue was diagnosed with breast cancer, and became a patient herself.

BLOOM: Why was there a need for your book?

Sue Robins: There’s a big imbalance in favour of evidence-based, data driven health research, and not enough about the feeling part of health care. We need more arts and humanities infused into the system. Health care is about art and science, and we’ve lost the art piece. Academic research is important, but it needs to be balanced with stories about the authentic experiences of patients and families. Health organizations don’t do a good job of sharing those. We need to talk about how it feels in health care—for patients and clinicians.

BLOOM: What messages do you hope people take away?

Sue Robins: That health care is desperate for more tenderness—both for patients and families, and for the people who work in it. That’s what I’ve realized on my recent book tours. I’m hesitant to use the word kindness, because that seems like ‘being nice’ to me, and we need more than that. It’s being tender and treating others with care and respect when they’re vulnerable and fragile. We’re missing a lot of that empathy-based care, as health care is pushed towards efficiency and doing more and more with less.

The second thing is that I only write about myself and my experiences to provide an example of how we need to own our own stories. I hope I can influence others to speak up in the same way.

BLOOM: What was the most challenging part of writing the book?

Sue Robins: I documented everything. I had been writing about having a kid with a disability forever. Then when I got cancer three years ago, I wrote about that in a personal journal. Surprisingly, the challenging part wasn’t writing about the painful parts of my cancer treatment. The challenge was some of the self-realizations I had along the way.

Arthur Frank says writing is not an act of reporting, but an act of discovery. I found some uncomfortable truths about myself, and one was about the fact that I was in such grief when my son was born because of my own ableism and the way I felt about disabled people. That was a very shameful realization that came to light.

The other challenging part was the mental-health piece of having cancer. I ended up with a lot of mental-health issues, and I’ve been in ongoing therapy to find out why that happened, and doing my own inner work. Going back to my childhood stuff, and everything I’ve never wanted to look at. That’s what cancer forced me to do.

BLOOM: It seems ironic that you were told to toughen up in nursing school, but you found, as a patient, that clinicians with soft skills had the most healing effects.

Sue Robins: There’s a lot of irony in my dropping out of nursing school because I had so-called ‘thin-skin’—and then really needing those caring hearts when I got sick. I don’t want to talk for other cancer patients, but for me, when I was feeling fragile and vulnerable, tender care was what I needed. Ironically, health care often weeds those people out. I admire those folks with tender hearts who stay in health care: the people who can do the technical piece of being a clinician, and have their heart open.

BLOOM: There’s an interesting chapter in your book where you talk about how you initially wanted to change your son Aaron, to help him better fit in the world; then you wanted to change the world, to include Aaron; and then you decided you could only change yourself.

Sue Robins: I would never, ever say that cancer was a gift, but putting me in therapy was a gift. I had spent a lot of years advocating and railing against the system, and being outraged. I think I was sold, and bought, the lie that we parents, especially mothers, are responsible to change the world to make it a better place for our kids.

But it’s a collective responsibility, it’s up to all of us. I can’t be outraged at the system without realizing my part in it. I feel I’m 'over' blaming the system, and I want to see how I can make change within my world. I think I believed I could change the world by giving one talk or writing a book. But it’s up to other people whether they take my messages, and what they can do one person at a time.

BLOOM: You wrote about your role as a ‘mama bear’ while advocating for Aaron, and how it, in some ways, hid your own vulnerability. How did your emotional world change when you became a patient?

Sue Robins: I got turned upside down, man. It was chilling. I felt like everything had been stripped away. I think when I was being Aaron’s mom, I hid behind him in some ways. I was protecting him—it was a role, a costume I put on. It was armour, to protect him, but I was also protecting myself, so I didn’t have to look at myself. I only had to look outwards all the time, at the injustices to disabled people. And there are a lot. I didn’t ever look at myself in that. I call cancer my great reckoning.

It brought me to my knees. It’s extremely personal, because your own cells are turning against you in your body, so there is nothing to hide behind. I was more vulnerable and more small and more fragile than I’d ever felt in my life. And I was a terrible advocate for myself.

People kept saying ‘Just do what you do for Aaron.’ But it’s not the same thing. It’s different when it’s about you, and not someone you love. It stopped me in my tracks.

For people who have had cancer, there’s a huge mental-health component, and no one talks about it. That was part of the book, too. My biggest fear when I was first diagnosed was ‘Who is going to pick Aaron up from school?’ I was in a panic about that. It was a metaphor for who will look after him after I’m gone. Then there was this personal crap all over the kitchen table that I’d never dealt with, because I was too busy dealing with other stuff, trying to change the world. And it was terrifying, but necessary, work.

BLOOM: You write about the great care your tumour received, but a system that turned you into a number, stripped you of dignity and ignored your emotional pain. I have a friend in Toronto who had a very similar experience with breast cancer treatment. I just can’t fathom why, when cancer is such a mainstream illness, we haven’t invested in making it patient-centred, and treating the emotional side.

Sue Robins: You’re the only person who’s ever stepped up and said that. I had a similar expectation, and I was totally wrong. You’re staring at your mortality, you have an illness that can kill you, and the treatment is hard. I expected I would be treated like a human being. But when I went to see my oncologist or surgeon, the opposite happened.

I’m not sure why, but in the oncology world, the clinicians and all of the staff put on this heavy armour. Is it so they don’t get close to you, because you might die? I hardly ever saw their hearts. The message I got for the most part was ‘Shut up, deal with it, you’re lucky you’re not dead.' And then: 'We’re done with you, we're discharging you, and you need to get back to your old life.' But the problem with cancer is that you never get back to your old life, because your life has changed.

For some reason, the professionals only focused on my breast tumour, not even the rest of my body. I don’t think anyone ever took a full history on me. It was just my left breast. They totally forgot about the rest of me. By minimizing and dismissing my physical and emotional pain, they caused a lot more harm—totally preventable emotional harm.

Cancer treatment is still so barbaric, and they would say things like ‘You don’t need chemo, you’re so lucky.’ You’re supposed to be grateful to be alive, and I am grateful, but come on! There was no tender care. It made me so sad, and no one talks about it. I told my doctor I was having a lot of anxiety and she said ‘Of course you are, you have cancer, here’s a prescription for Ativan,’ and that was the end of the conversation. I was looking to her to show that she cared about me.

I tried to go see them at my cancer centre and tell them to turn off the TV in the waiting room, and that I could help them with the patient experience. They weren’t interested.

Patient-centred care doesn’t fit into their model. They’re super specialized and they’ve embraced the expert model. Maybe they feel pity for us.

BLOOM: You’ve recently given talks at Holland Bloorview, and a number of Toronto teaching hospitals. Did you find anything in particular resonated with your audiences?

Sue Robins: The audiences were mostly staff, and I did readings and a commentary on conversations about kindness. I realized how much everyone is hurting, and everyone is vulnerable in health care, including the people who work there. This has been part of my learning since the book came out. I realized that if I want professionals to treat me tenderly, as a mom and a cancer patient, I also had to treat them gently, and with the kind of care I want to have.

As a patient, I want us to see each other. But clinicians have to allow themselves to be vulnerable enough that we can see them, and catch a glimpse of their heart. That’s where client- and family-centred care is intertwined with staff wellbeing. We have to talk about both.

BLOOM: You wrote about an interesting switch in emphasis in your daughter Ella’s first clinical placement as a nurse. Instead of focusing on tasks, the students were asked to sit and talk with patients.

Sue Robins: I think her university did that purposefully, and she’ll be a different kind of nurse because of it. By teaching the human side first, they showed its importance. The technical tasks can be learned afterwards. Her second rotation was mental health, and a big part of that job was also to sit and listen with patients, not run around, which happens in a lot of hospital units.

BLOOM: I loved your book because each chapter can be read as a self-contained unit with a related quote at the top. It’s something a person can pick up and, in the space of a few minutes, pull some wisdom.

Sue Robins: I want it to be a springboard for conversation. I’m hoping professors in health-care faculties will assign a chapter as required reading. It could be on sharing news, or on patient mental health in cancer, or on disability. That’s why they’re short, because that’s how people read today, in short snippets. The stories are something everyone can reflect on and talk about.

Stories remind professionals of the meaning of their work, and why they went into health care in the first place.