Trying to 'fix' a missing ear caused a lifetime of trauma

By Louise Kinross

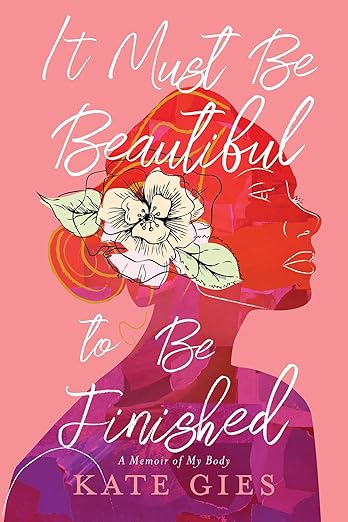

Kate Gies was born without a right ear. In her memoir It Must Be Beautiful To Be Finished, the Toronto writer recounts the relentless efforts of plastic surgeons to “make her look normal.” Fourteen surgeries didn’t produce the desired result but did leave Gies with a sense of body shame and post-traumatic stress disorder. We spoke about her childhood.

BLOOM: Within days of your birth, a plastic surgeon told your parents he could create an ear, even though you wouldn’t hear out of it. It sounds like the medical focus was on fixing what made you look different. Was there any discussion about the pros and cons, and possibly doing nothing?

Kate Gies: I don't think so. After I was born my mother was asked if she drank during pregnancy. They also told my parents that I may never walk, see or hear, so a lot of fear was built up. Then a plastic surgeon came in and said: ‘I can fix this.’ I don’t think from the medical staff perspective it was seen as an option to not intervene. It was 1978. It was only supposed to be three surgeries, so it wasn’t seen as a big risk. It was seen as an easy fix, a no-brainer.

BLOOM: The first plan was to slip a plastic ear under skin taken from your buttocks. The surgeon said: ‘Once we slip it in, no one will ever have to know you didn’t have an ear.’ What happened in reality?

Kate Gies: Essentially that didn’t happen. The first surgery they took a large square of skin from my buttocks and placed it where the ear would go. Then they slipped the plastic ear under it. Within a couple of weeks, my body rejected the plastic, and it became very infected. They had to take it out and they tried again. The second time it also became very infected, and they had to take it out again. After five surgeries in Kingston, Ont., the surgeon suggested I go to SickKids Hospital in Toronto.

BLOOM: What was the approach at SickKids?

Kate Gies: The new plan was to take cartilage from my ribcage and form it into an ear, instead of using the plastic. In the first surgery, a tissue expander was inserted under the skin on the right side of my head. Then I went to the hospital weekly to get saline injections to expand the skin so that the doctors could eventually insert my rib cartilage underneath.

After a few weeks it all got very infected, and the doctors removed half of the tissue expander in hopes of salvaging the rest. I then got another infection and they had to remove all of it. They still went ahead and cut out cartilage from my ribs and inserted it under the expanded skin.

That was the most violent surgery I had. I was in a lot of pain after the rib removal. Even today it’s very uncomfortable in the area the cartilage was removed.

Subsequent surgeries included skin grafts to form the ear lobe, adjust the ear lobe, and contour the shape of the ear. The surgeons also pinned my left ear to my head to approximate the position of the right ear they were building.

I was never sure when I woke up what was going to be changed about my body. It was never the magical perky ear I'd imagined, but instead, snakes of stitches and scars. Swollen bits, redness, blood, and bruises.

BLOOM: You write about two Kates—the Kate you were and the Kate you were supposed to be. How did that impact your sense of self?

Kate Gies: It split me. There was an ideal version of me that existed only in my mind and the imagination of the doctors. Every time something happened to me—if I got made fun of, or didn’t make the volleyball team, or someone rejected me—there was this other Kate living simultaneously in another dimension who didn’t have to deal with that. She had lots of friends and people didn’t make fun of her. There was a splitting of my self, and I was the bad version. I compared myself to 'The Kate I Was Supposed To Be' constantly.

BLOOM: What do you think might have happened if your parents said no to the surgery?

Kate Gies: It’s possible I would have resented my parents for doing nothing. Because I wouldn’t have known how it was going to turn out.

I say in the book that the tragedy of my body was the attempted fixing of it, not being born without an ear. As a child, I never acclimatized to being put to sleep in the very foreign environment of the operating room. My anxiety got worse every time. I have a lot of residual trauma in my body from the surgeries and I was diagnosed in my 30s with complex post-traumatic stress disorder.

Being exposed constantly to plastic surgeons meant that I didn't have good boundaries for my body. All my surgeons were older men and they were allowed to touch my body whenever they wanted to. That affected me as I got older in romantic relationships, because I didn’t know how to own my body.

The plastic surgeons also had very specific opinions about the 'wrongness' of my body. The very idea that there is something so wrong with your body that we must do violent things to it to make it okay made me feel that my body was bad. I’ve been given the message my whole life that there is something very wrong with my body.

BLOOM: They kept doing surgical revisions and three surgeries turned into 14. Did you ever get angry at the surgeons because they misled you on what to expect?

Kate Gies: It never occurred to me. The anger always went inward: Why can’t my body accept this plastic ear? Why did my body reject the tissue expander? Why is my body not behaving well? It never occurred to me to get mad at the doctors.

BLOOM: At age 14, when the surgeons are planning more operations, you say no. How did you get to that point?

Kate Gies: I wish I could say I got a good sense of myself and the feminist in me blossomed, but that wasn’t it. I was at a point where my body couldn’t take it anymore. I was so tired of being cut into. Surgery is a violence, whether it’s necessary or not. I was also about to start high school. I always did well in school, and I didn’t want to constantly miss it for surgeries.

BLOOM: At age 13, a surgeon shows you that your smile is asymmetrical and tells you it can be fixed in a few surgeries. What impact did that have on you?

Kate Gies: My smile suddenly wasn’t about feeling joy. It was this thing that subtracted from my physical appearance. So I stopped smiling. Or I closed my mouth when I smiled, and I became very conscious of my crookedness. It became another way my body was not performing well.

BLOOM: I remember a plastic surgeon pointing out two ways that my young son’s face was not symmetrical, but I, as his mother, had not noticed these things. It was very unsettling.

Kate Gies: Doctors constantly pointed things out about my face, even to this day. Your mouth is crooked, this eye is different. I think we live in a world, especially now, with the advent of social media filters and more advanced medical technology, where we believe we can fix everything. Just because you can fix something doesn’t mean you should.

BLOOM: What did you learn about the importance of symmetry in our culture?

Kate Gies: We’re taught that symmetry equals beauty. But bodies aren’t perfect. I think plastic surgeons think of bodies in very linear ways. It’s sort of an unhealthy obsession to try to make a body perfect. It’s an impossible goal.

BLOOM: How much time did you spend trying to hide your lack of an ear?

Kate Gies: I think as a little kid I didn’t hide it. I would wear these very large, gauche earrings on one side. I hadn’t been indoctrinated into the idea that bodies were supposed to look a certain way.

I started making myself small around the age of 12 and 13. That’s when what you look like feels like the most important thing. I kept my long hair down or in a low, messy ponytail when playing sports. I worked at Licks and I remember my boss saying: ‘Your ponytail is too messy.’ But I’d rather get fired than show that I had this ear.

I also hid the scars on my body. I’d wear granny underwear as a young adult to hide the scar on my buttocks. I always wore one-piece bathing suits. In the change room after gym class I'd be super vigilant about how to remove my shirt so people wouldn’t see the scars on my chest and belly. I stood to the right of people to keep the 'bad ear' away from them. I'd turn in certain ways when being photographed to minimize my crookedness. All this hiding was exhausting.

BLOOM: In your book, you say asking someone about a body difference is a form of violence. Can you explain?

Kate Gies: I think people with facial difference, or any kind of body difference, often have some trauma related to it. Maybe you got into a car accident and have a scar on your face, or you’ve had years of bullying or gone through many surgeries. I shouldn’t have to relive my trauma to satiate your curiosity.

I’ll be going about my day and someone will say ‘What’s wrong with your face?’ Even asking that feels abusive. Your body is the vehicle within which you are in the world. Being asked about why something is wrong with it suggests there is something inherently bad about you.

BLOOM: In rehab, children are often taught that it’s their role to educate peers about their differences. There's an interesting book called What happened to you? by a disabled author that pushes back against that. You note there are cultural ideas about why someone is born with a physical anomaly. For example, did the mother do something wrong?

Kate Gies: These ideas give people a sense of control of their body. That if they behave right, that won’t happen to me.

I think there’s a deep cultural fear of body difference and it comes down to a fear of mortality—a fear that bodies change and can break down. So instead of understanding that all bodies, if we’re lucky enough to live long, will change, we ‘other’ the people who have the body difference, so we can keep our distance from it.

It’s interesting because when I published the book, I think my mother was afraid because she was holding on to some shame, too. ‘Let’s blame the mother’ has been around for centuries. I don't think this was the case for my dad.

We also live in a world where people with facial difference are often portrayed as villains in the media—think James Bond or Batman movies. Villains often have some kind of facial difference or disability and the message is reinforced that having a different body makes someone bad.

BLOOM: What do you hope doctors take from your story?

Kate Gies: I love this question, and no one is asking it. For me, the best doctors have been the ones that have spoken to me like a person not an object. They’ve shown a grace and empathy towards me, don’t make assumptions, and don’t ask questions out of curiosity.

Doctors need to understand that patients are the experts on their bodies. Perhaps when talking to children and parents, a doctor could say: ‘Here are some options’ and include ‘You can do nothing. Or perhaps you’d like to have some counselling to help you consider things.' And also drive home the point that there is nothing inherently wrong or 'unhealthy' about a child with a facial difference.

Doctors need to understand the cultural and societal messages about body difference that impact their own biases and understanding. They need to interrogate their own ways of reinforcing negative messages. This is so important as doctors are culturally seen as an authority on the body.

I think a big question doctors need to ask themselves, especially when working with people with body difference, is: 'Why are you pushing this surgery?'

Doctors need training around their role in disability awareness and body image. Do you look at body difference as a sickness? If so, what are you missing out on that you can learn from your patients?

Also, doctors need to understand their role in mitigating medical trauma. Medical trauma to the body is often unavoidable, but what doctors can do is show kindness, empathy, and genuine care for the wellbeing of their patients. I firmly believe that the relationships doctors have with their patients can greatly diminish the effects of medical trauma. Especially for children.

Doctors need to be conscious of how they are relating to their child patients in real time. Are you going to be the doctor who tells a 13-year-old child that her face is crooked? What implicit messages are you sending in your clinical evaluation? How can you be better at making sure that the patient doesn't leave your office feeling like shit? The relationship you have with a patient absolutely affects their health, their trust in you, and their sense of trauma.

I talk in the book about a meeting with my pediatrician, who I had a good relationship with. One day she brought in a resident and started talking to him as if I was a freak of nature. That felt like such a betrayal of trust. I couldn’t articulate it at the time, but I did ask my mother: ‘Why didn’t you put me to sleep when I was born?’

Kate Gies is a writer and teaches creative nonfiction and expressive arts at George Brown College. Like this content? Sign up for our monthly BLOOM e-letter, follow BLOOM editor @LouiseKinross on X, or watch our A Family Like Mine video series.