Scientist uses drawings to reveal children's perceptions of concussion

By Louise Kinross

Fear over facts.

That’s one of the main findings of a qualitative research study conducted by Holland Bloorview PhD candidate Katie Mah, where children were asked to draw what they know about concussions. Katie, who is an occupational therapist (OT) and nurse, has an interest in bringing a child and youth perspective to research that has traditionally been informed by adults. Katie came to Holland Bloorview in 2013 to work with Nick Reed in our pediatric concussion centre. As a hockey goalie and dancer growing up, she had firsthand experience with concussions. We talked about her arts-based research method.

BLOOM: How did you get into this field?

Katie Mah: I knew I wanted to work in rehab in some capacity. My father is a family doctor who worked at WestPark, and I spent a lot of time there when I was younger. I thought I’d be more engaged in my undergraduate studies if I went through an applied degree first, and craved the hands-on clinical skills I knew I'd get through nursing. As a nurse, I worked with adults in cardiology. But then I was injured on the job and spent over a year in rehab, working with a lot of different health professions.

I became very interested in the rehab side of care, and I lost my passion for my previous job. When nursing, we were always short-staffed and under-resourced, and I thought another injury was likely if I went back. I knew lots of occupational therapists, and it seemed that no matter what population or age group they worked with, they were all really fulfilled in the profession. I also felt I could have a longer-lasting impact on somebody’s life in rehab, in contrast to acute care.

BLOOM: How did you end up working on concussion?

Katie Mah: Nick Reed had actually taught me research in the OT department at U of T, and it was the first time I really enjoyed research. Then I worked clinically as an OT for the VHA. I worked in schools and homes with children with disabilities. I had an interest in the broader area of brain injury because I’ve had three concussions.

Nick was looking to take on a PhD student, and remembered that I’d enjoyed research, had played a lot of sports with a high risk of concussion, and enjoyed working with children. He called me in August, and I started in September.

BLOOM: Why was there a need for your study about children’s perceptions of concussion?

Katie Mah: As an occupational therapist, one of our central tenets is that we’re client-centred. So when I began reading in the area of concussion, I wanted to research something that children who had experienced concussion had identified as meaningful to them. But when I looked at the literature, there was very little informed by children. I wanted to understand their priorities, but at a more basic level, I realized I needed to know what children knew or thought or felt about concussion first.

BLOOM: How did your study work?

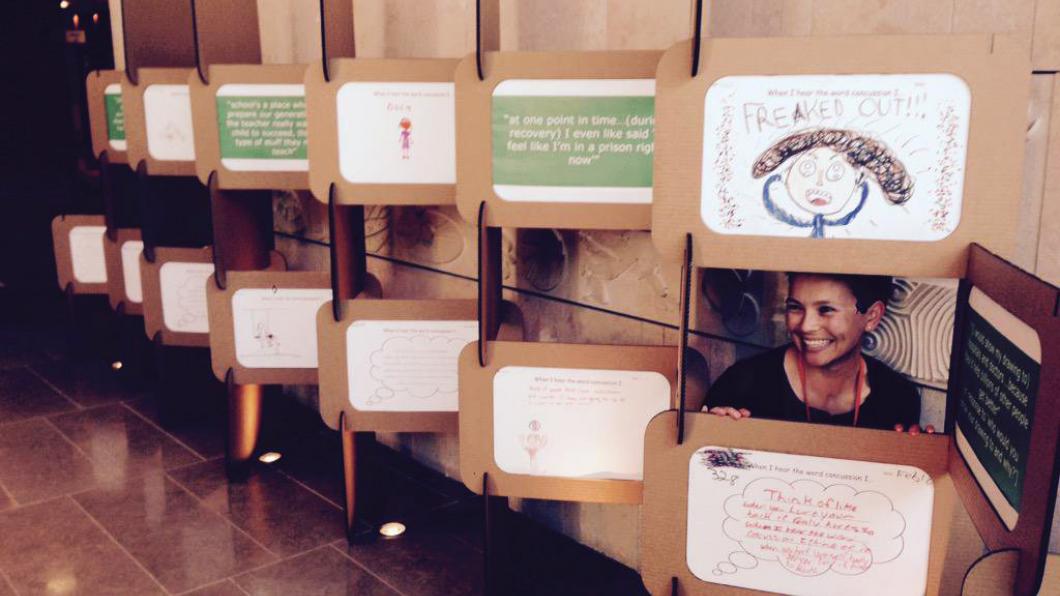

Katie Mah: It was part of the Research Live exhibit at the Ontario Science Centre. We had children and youth aged six to 18 participate. Some of them had personal experience with concussions, and others hadn’t. Each child was given a large piece of paper.

If they hadn’t had a concussion, at the top of the paper was the phrase ‘When I hear the word concussion I…’ It was very open-ended and they were asked to draw whatever they thought or felt. For children who did have a history of concussion, there was a line down the middle of the page and on the left it said ‘Before my concussion I…’ and on the right it said ‘Now I…’ and they could draw how their thinking or feeling had changed, if it had.

Afterwards I did a semi-structured interview where I started off by asking them to explain what they drew. I also asked who the intended audience was. Who did they draw the picture for, and what did they want that audience to know?

BLOOM: Why did you decide to have youth draw pictures, as opposed to tell you what they thought?

Katie Mah: I didn't have the opportunity to build rapport with the young people in my study, since I would only see them once. Because of this, I wanted to engage them in a way that would hopefully not be as intimidating as an interview alone, and with an activity that they could do mostly on their own at first.

As a research method, drawing is also known to give participants a lot of freedom, flexibility and time for reflection. I knew many participants likely hadn't thought about concussion explicitly before, and so I wanted to give them time and space, using a method that would allow this.

BLOOM: Did you get any push back about using art as the medium for your research?

Katie Mah: I wouldn’t say from an ethical standpoint, and not, overtly, from a legitimacy standpoint. However, I have this sense that my research is often understood as ‘cute’—or just innovative or creative for the sake of innovation or creation, without that understanding that arts-based methods can actually lead to new and different, not just more, knowledge.

BLOOM: What were the key results of your study?

Katie Mah: I've generated all my data, but haven't finished analyzing it yet, so my results are still preliminary. I’m writing my thesis.

But children are very afraid of concussion—whether they have a basic scientific understanding of it or not. So there are children who aren’t able to define it, but know inherently that they should be afraid of it. A lot of children think that concussion can have much more serious, long-term, and even fatal consequences than are typically seen in clinical care. The children who haven’t had concussion themselves see it as an injury that will absolutely have lasting effects.

From the children who have personally experienced concussion, you hear much more neutral stories. They had this injury, the recovery may have been difficult for some, but they’re doing okay now. They may still be somewhat fearful, but overall, they’re doing quite well. I don’t think these neutral stories are shared as much as they should be.

BLOOM: Were you surprised by the results?

Katie Mah: Yes. For the children who hadn’t had concussion, I thought they would state medical facts about the condition and its symptoms, but it seems the fear piece has taken over.

For the children with personal experience, I thought they would speak more to how concussion impacted them day to day—with effects on their emotions, relationships and social life during recovery and after.

Concussion has physical and cognitive symptoms, but it can also lead to sadness and anger and withdrawal from social relationships. Some of the participants did experience that, but the way I understand their data is that they've worked through those issues. Some are saying concussion 'doesn’t affect me at all'—it can be that insignificant.

I was also surprised by the number of participants who wanted to tell me all they had learned as a result of having a concussion. They had so many ideas about what we need to do differently.

BLOOM: What’s an example?

Katie Mah: They felt education should be provided at school as part of the health curriculum. They also felt they would be good teachers, because they personally have experienced the injury. They said they thought they knew what concussion was before they were injured, but they didn’t really ‘get it.’ Now they really got it.

BLOOM: How will you use the results?

Katie Mah: A lot of it is in the how. The education is happening, but it should be informed, in part, by what children and adolescents have to say about it. If we look at the media, a lot of the current education is fear-based, and I don’t think that’s the best tactic. We need to be careful, but we don’t need to scare kids into changing behaviour. Kids are smarter than that. Fear isn’t the way to get us where we need to be.

BLOOM: What was the greatest challenge of this research?

Katie Mah: Quite honestly, it's been frustration. I've been frustrated that as a society we take the knowledge and voices of certain groups much more seriously than the knowledge and voices of other groups. I think the voices of children and adolescents are less valued than the voices of adult researchers, and the social sciences are less valued than biomedical sciences.

Particular kinds of people and research will always be regarded in higher esteem than others. I think this makes us miss out on a lot of important knowledge.

BLOOM: It reminds me of the interview I did with Julia Gray about her research into our therapeutic clowns.

Katie Mah: You can’t quantify a clown!

BLOOM: Yes. Julia was talking about how the clowns’ work is so valuable because they’re willing to fail and be flexible and in the moment. But that approach makes academics nervous. Because in some ways, science is like a shield that protects you—so you can always be right.

Katie Mah: I do agree with that. To me, it’s frustrating that expert knowledge is always seen as more credible. The experts in research aren't always the ones with the most academic training. In my post-doctoral studies, I want to continue working with children who experience concussion. But I see a future for these arts-based methods in children’s rehab with any number of populations.

BLOOM: I think we would get so much from asking kids to draw their experiences of rehab.

Katie Mah: The reason I want to speak directly with children and youth is that we often don’t consider the effects of our ways of thinking and practice on children who are receiving services.

BLOOM: I think drawing can convey experiences and perspectives in ways that can be hard to describe in words.

Katie Mah: It’s more 'in your face' than a transcript. And it’s accessible.

BLOOM: Anyone can see and understand it. A drawing doesn’t exclude people, the way academic jargon does.

Katie Mah is now located at the OAK Concussion Lab at the University of Toronto. You can follow the lab @OAKConcussion.