In 2019, physical restraint of disabled people still is a thing

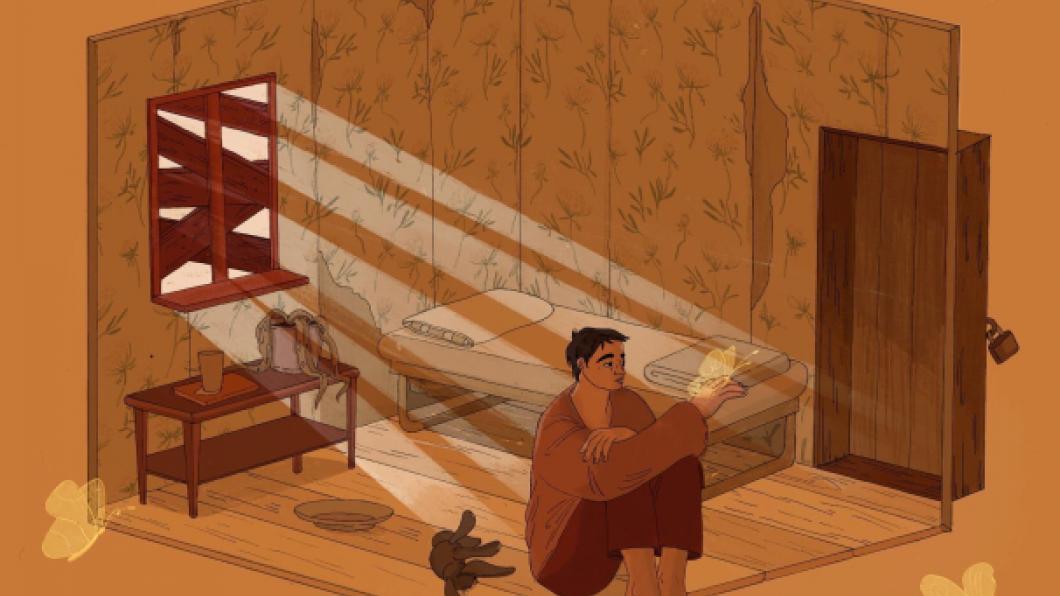

Illustration from Captive and invisible

By Louise Kinross

A couple of months ago I wrote down 'physical restraint and seclusion' as a story idea. But when I looked at it on the list, I kept hoping there would be a reprieve.

Instead, every time I went on social media there was a new horror story about disabled children and adults who were restrained, physically or verbally abused, or locked in a school isolation room, hospital, assessment unit or 'care home' for adults.

Yesterday, I read Captive and invisible. It's a series of stories about disabled people who are locked away in hospitals, institutions and private homes. It was produced by the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of persons with disabilities. One of the stories is about people in Ghana, for example, who are sent to prayer camps, to be healed, where they are shackled and live in horrendous conditions. Catalina Devandas Aguilar, the UN expert, discusses the series here.

The selection of stories, such as the one in the image above, suggests that the problem is in developing countries. "Amil is autistic, and he lives in a rural village with his family," is the text that accompanies it. "They have no help, and there are no services in the community, so he spends all his days and nights locked up in a room."

But this isn't just happening in low-income countries. It is happening in Europe and the United States and right here at home in Canada.

Last month, the BBC aired a shocking investigation into a British home for adults with autism and intellectual disabilities. The home, funded by the National Health Service, is referred to in the British press as a 'specialist hospital for people with learning disabilities,' which is the term used there for intellectual or developmental disability.

A reporter went undercover as a worker and filmed her colleagues taunting, intimidating, degrading, provoking and repeatedly restraining patients. They bragged about times they'd assaulted patients, like banging a person's head against the floor. Then it was revealed that patients had reported bullying by staff in an inspection report in 2015 that was never published. Last year, the home was bought by an American multinational company. What interest, other than monetary, could a U.S. multinational have in a British hospital for people with intellectual disabilities? Ten staff members were recently arrested.

A similar case in New York City came to light five years ago in a home for adults with developmental disabilities dubbed the "Bronx Zoo" by staff. But despite an investigation that found staff at the state-run home smacked, pushed and punched residents, New York State officials who tried to fire 13 employees for abuse or neglect were unsuccessful.

According to an article earlier this week in The New York Times, the workers were shielded by the state arbitration process. In addition, The Times found that over one-third of employees statewide found to have committed abuse offences at group homes and other facilities between 2015 and 2017 were put back on the job.

Which reminded me of my own son's experience back in 2009, when a school staff member, angry because he picked a butt up off the ground in a park, and pretended to smoke it, dragged him across the playground and pushed him into his wheelchair. He had a dislocated hip at the time. Other staff reported this person, but the principal didn't deem it necessary to call me until 24 hours later, when she asked if my son had told me about an 'incident.' No, he doesn't speak, he hadn't, I said. It wasn't until that night, when I asked him about it, that he signed the story to me. He never would have told me otherwise.

The staff member was sent home, the police were called, and I was asked to check for bruises. I was told that the staff member would never be in a class with my son again. Imagine my surprise, then, when the following year, this same staff person turned up working at the mainstream school my son had transferred to. And had the nerve to approach, and talk, to my son. So I had to call the principal and read him the riot act that this person was to have no contact with my son.

Only two days ago, this piece in The Globe and Mail summarized the Canadian practise of physically restraining or isolating, in locked rooms, children with autism or other disabilities who "act out." Sheila Bennett, a professor at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ont. was quoted as saying she was horrified to hear about a plan to build more seclusion rooms in Ontario school districts. "When an isolation room exists, it becomes a viable alternative for behaviour and inhibits our ability as experts and educators and compassionate people to find solutions that work better," she said.

In April, a British teenager with autism and mental health problems who had spent two-and-a-half months in an isolation booth at school, a variation on the isolation room, where students sit in cubicles in silence and have no direct teaching, tried to kill herself. Her mother said she was unaware, for months, of what was happening.

I'm not an expert, but how could any educator possibly imagine that a child with autism and anxiety would blossom sitting alone in silence?

Just yesterday, I read a post in a closed Facebook group for parents of children with disabilities where a local parent asked if a school has to document every time a staff member physically restrains her child. She'd been asked to pick up her young child in the morning, and it was only after he was in the car that she learned that a teacher had put him in a hold.

A teacher can restrain a child in a physical hold, and not tell a parent about it?

In 2019?

In another Ontario online group a parent spoke about how her adult son with autism has spent months in a locked psychiatric hospital because there are no options for him to live in the community. And she knows of a handful of families in similar situations.

Last week the photo below was tweeted by many British parents to show what it's like for a parent in the U.K. to visit their autistic teen who is locked in an inpatient mental health facility.

How did being held like a criminal become an accepted practice for disabled children and adults in our schools and hospitals and group homes?